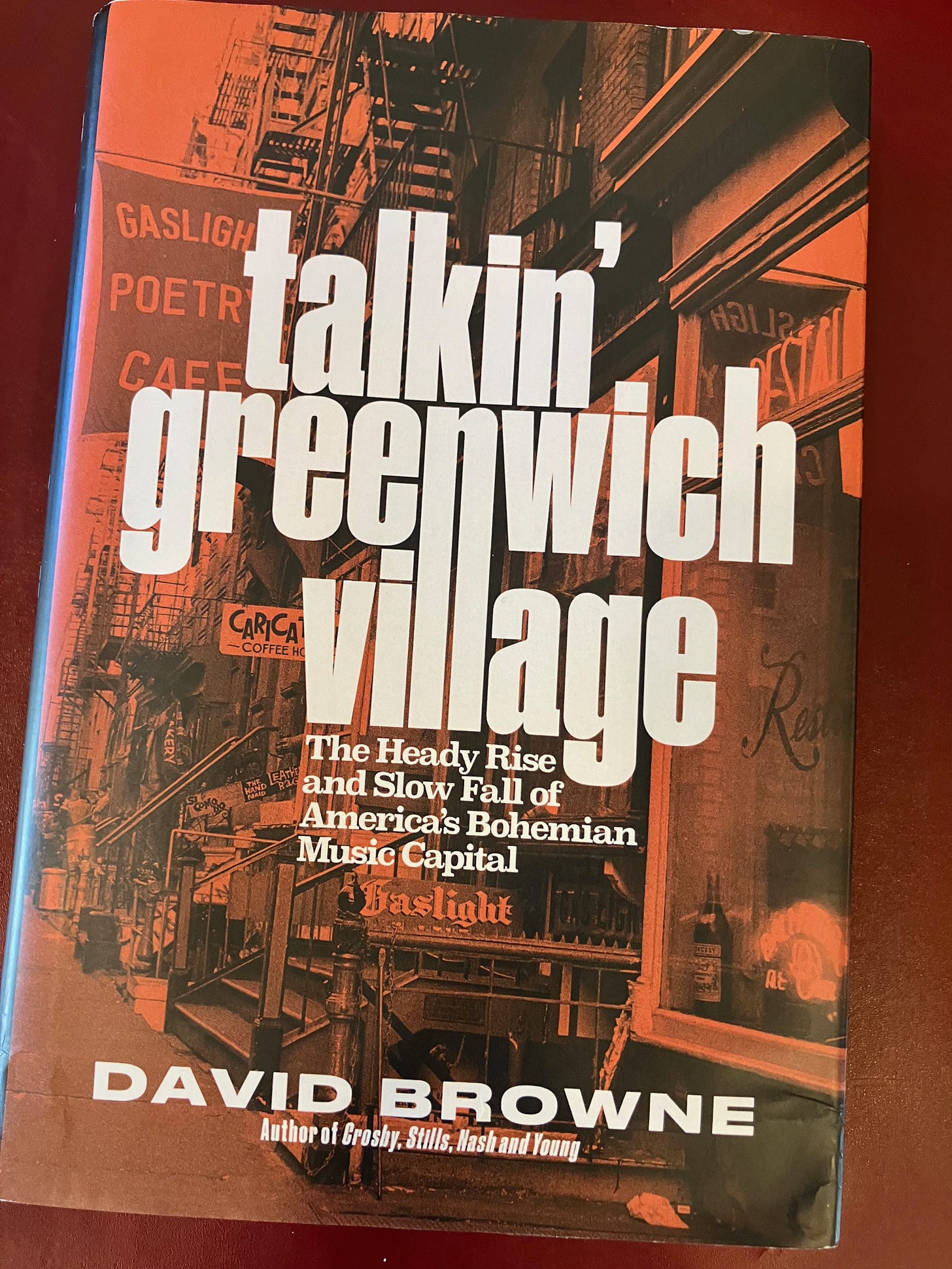

Talkin’ Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall Of America’s Bohemian Musical Capital by David Browne (Hachette, 2024)

THE VILLAGE. Let me briefly expound on the vision conjured by these words in my young imagination, fifty years ago and long before I had ever visited that New York City neighbourhood: a well trimmed picture-book green, the clean gurgle of a tempered fountain, the clink of coffee cups and the meld of gruff and angelic voices spilling from the historic bars, spreading gospels of freedom and release, maybe boho buskers filling their corduroy caps with sparkling nickels on the sidewalk plus the cosy bleat of a lightly-tethered goat.

Of course, twas never thus, but even after I went to Greenwich Village, a somewhat faded, jaded outpost, its golden age tarnished by changing trends and a bankrupt City Hall by the time I turned up in 1978, popped into its corner coffeehouses and basement pubs and strode the somewhat rutted jumble of criss cross streets, I could not entirely banish the nostalgic picture my juvenile mind had conceived in those previous years.

Talkin‘ Greenwich Village, David Browne’s brilliantly-detailed history of a unique urban space, does not over-romanticise the story of this downtown terrain for a moment. In fact, while this Manhattan-based journalist, who has previously released rock biographies of CSN&Y and Sonic Youth, the Grateful Dead and Buckleys both senior and junior, has a deep affection for this part of his home city and its creative works, he doesn’t suggest this journey has ever been smooth or straightforward.

From early interwar mob interference and the punchy resistance of Italian immigrant families to bohemian ingress to parks commissioner Robert Moses’ maniacal scheme to bulldoze a highway through the heart of this artistic enclave plus the maze of licensing regulations that would haunt promoters, the odyssey of music and theatre, poetry and entertainment, has felt the strains imposed by city officials, commercial developers and conservative residents during its more than one hundred years of street level activity.

Within this richly diverse community, styles and fads move through phases – jazz and cabaret in the 1930s, a literary upsurge during the 1950s, the folk revival as the 1960s unfold and then, by the 1970s, a fresh generation of lyrical singer-songwriters rising through the ranks. But where does Beat sit in this ever-changing sequence of performers and audiences?

Browne certainly acknowledges the presence of these writers – he mentions Ginsberg and Corso, LeRoi Jones and Kerouac, reading at the Gaslight – and, from the very opening lines of this grippingly tangled tale, Jack’s great musical friend David Amram wanders on to an eclectic stage and reappears several time as the decades roll by.

Yet, in this book, as the author unwraps something of a boom-and-bust history, squeezed by social tensions, fired by artistic invention and bolstered by entrepreneurial intent, it is the term ‘beatnik’ that is the more regular visitor to the narrative, at least in the first half of this overview.

Beatnik has a somewhat disputed genesis – was it San Francisco columnist Herb Caen linking the Beat Generation poets and novelists to Sputnik thereby Soviet entryism in 1958 that gave the term such a pejorative flavour? – but it certainly became a byword for the kind of loitering itinerant and daytripping drifter many Greenwich Village residents found hard to stomach around this time.

The bona fide authors, of course, hated the association with the cartoonish characterisations of that new subcultural strain but it wasn’t just stick-in-the-muds who were keen to keep the beatniks at bay. Even Dave Van Ronk, the so-called Mayor of MacDougal Street, a committed leftie and a central figure in the folk revival, found the presence of those young insurgents an unpleasant ingredient in the local mix.

As Browne explains, Van Ronk ‘actively disliked the fake beats – with their goatees, berets and bongos – who were suddenly popping up […] calling it “horseshit”.’ But the singer ‘admired the actual poets’.

This uneasy integration would all come to a somewhat ugly head in April, 1961 when the so-called ‘Beatnik Riot’ erupted, though this was something of a misnomer, a lazy media shorthand for a demonstration by folkies and politicos, artists and writers, which was attempting to protect the role of Washington Square Park as a focal point where acoustic musicians and their fellow travellers could convene and mix together at the weekends.

The regular concentration of such types caused deep irritation to many of those who lived in the vicinity and particularly police officers who saw this largely innocent gathering as a focus of crime, petty or otherwise, dope deals and more. A trend towards racial miscegenation was also blamed for the attempted clamp down on this constituency. But these outdoor sessions were no more really than a vocalising platform for a little polite protest and they quickly resumed despite the trouble raised by this headline-grabbing flare-up.

In this snappy and vivid account there are a thousand such Village stories to relate. Some are dark – visiting bluesman Mississippi John Hurt walking with his white female companion explaining that he was constantly nervous because he expected to be lynched – some quirky – the rise of finger snapping to express a crowd’s approval and thus avoid noise abatement notices for loud clapping – and some revelatory – palpable tensions in the mid-1970s when on-off inhabitant Dylan was recruiting his Rolling Thunder cast (poets Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky and Anne Waldman would eventually join the touring Revue) and rivalries were pretty raw.

There are hundreds of further musicians on whom Browne can hang his anecdotal hat. A list including Woody Guthrie and the Weavers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Carolyn Hester, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez and Tim Hardin, Judy Collins, Howlin’ Wolf and the Blues Project, only touches the surface. Jazz giants like Billie Holiday, Charles Mingus and Miles Davis enjoy their own cameos. And the later stars who come out to shine – Patti Smith and Suzanne Vega, Shawn Colvin and the Roches – also find a place in the gradually wearing tapestry.

But the other potent strand that runs through the fabric of this survey is the one built on brick and stone: the dozens of venues which played midwife to a remarkable parade of talent – the Village Vanguard, Gerde’s Folk City, the San Remo, Cafe Bizarre, Cafe Wha?, the Bottom Line, the Bitter End, the Kettle of Fish, to name only some of the more celebrated.

In fact, one small supplement this richly researched tome might have included, to assist with my own Village geography lesson, is a map or two pinpointing the places and spaces of the various eras, as bars changed names and cafes switched location. But that is a small complaint set against the multiple themes and variations embraced by this well-crafted chronology.

THE LEFT BANK OF NYC. -when literary, musical, and cinema gods walked the streets of the Big Apple - fantastic story telling and a legendary cast of characters. Viva Rock & Beat Generation & David Browne for this treasure trove of the City that never sleeps. There are ten million stories in THE NAKED CITY- This it’s one of them.

A warm and wonderful review. I just saw, the other day, the documentary, the Ballad of Greenwich Village, which covers much of the same ground and has footage of many of the venues mentioned here. Both your review and the film brought back fond memories of the Village of my youth. My grandparents lived in Greenwich Village and I visited many times, often for extended stays. I loved strolling about the village as a child, especially Sunday afternoons when artists would line the street with their artwork. This until the City banned these impromptu Art Shows, which they ultimately failed to do with unlicensed street booksellers because the courts deemed the unrestricted sale of books free speech. Ginsberg lived in the East Village which had a very different flavor from Greenwich Village but was increasingly a center for bohemian, artistic, and countercultural life as Greenwich Village became hugely gentrified. Eventually, the East Village followed suit and the scene moved to Brooklyn and beyond.

It's important to remember that the Village for all its romance, reputation, and bohemian allure was also a town within a City where a richly connected fabric of people lived their daily lives, raised, their children and knew each other. In a city that could often be anonymous, the Village of yore was a place of warmth. Thanks again for your fine review.