Beat Soundtrack #12: Sharon Mesmer

In which prominent Beat figures, writers and critics, historians and academics, fans and followers, talk about the relationship between that literary community and music

Sharon Mesmer is the author of several poetry and fiction collections, the most recent being Greetings From My Girlie Leisure Place (Bloof Books, 2015). Her poems have appeared in Postmodern American Poetry: A Norton Anthology (2013) and I'll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women (Les Figues, 2014) among other places. Originally from Chicago, she became instrumental in galvanising the local poetry and punk rock scenes. When she moved to New York City, she became a student of Allen Ginsberg. He later described her work as ‘always interesting, beautifully bold and vivaciously modern’. Her writing has also attracted the tag ‘post-Beat’. She teaches at New York University and the New School.

What attracted you to the Beats? When did you first encounter them? Do you have a favourite text, novel or poetry?

When I was about 14 years old, I worked in my Catholic high school library. I worked there because I had so many detentions, beginning in freshman year, that, if I were to actually make them up, I’d probably be sitting in detention hall writing this. So, the principal accurately surmised that I would probably NOT skip out on that kind of gig.

The nun in charge of the library, Sister Patrice Marie, was young and really nice, and knew I loved poetry, and one day when I was stamping date-due cards at one of the big tables she came up to me with a smile on her face and a open book in her hands. ‘I think you might find this interesting,’ she said (or something to that effect), and presented me with an anthology of contemporary poetry, open to ‘Sunflower Sutra’.

Before that, my main exposure to poetry was whatever was in our English textbooks, which wasn’t bad or boring (the poems were honestly quite engaging: e.e. cummings, Gwendolyn Brooks, even Beatles lyrics) but this….this was different. The plain-spoken nature of the language mixed with flights of beauty, the prose-y format, that incredible final passage . . .

‘We’re not our skin of grime, we’re not dread bleak dusty imageless locomotives, we’re golden sunflowers inside, blessed by our own seed & hairy naked accomplishment-bodies growing into mad black formal sunflowers in the sunset, spied on by our own eyes under the shadow of the mad locomotive riverbank sunset Frisco hilly tincan evening sitdown vision.’

. . . made me feel like I’d stepped through some kind of portal into another world. I had to know all about that poet. In 1975, doing research meant getting on a bus and travelling an hour to the public library — if the school library yielded nothing — and that’s what I did, and how I discovered my future MFA professor and advisor, Allen Ginsberg, and the Beats.

I really can’t say I have a favourite work, by any Beat writer. The work is so various, and voluminous, and brilliant in different ways. But there is someone whose work I’ve been very involved with lately: Elise Cowen. Back when Allen was my teacher, he suggested I try to locate her work; he thought her sparse, Dickinson-like poems might inspire me.

It was hard back then, in the ‘90s, to find anything by her, aside from a selection that had appeared in (I think) Evergreen Review. But luckily Ahsahta Press released Elise Cowen: Poems and Fragments, edited by Tony Trigilio, in 2014. Previously, and unless one had read Joyce Johnson’s beautiful Minor Characters, Elise was mainly known as the last woman with whom Allen had a romantic relationship. But now her true brilliance is evident.

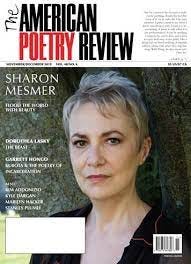

Pictured above: Mesmer on the cover of the American Poetry Review in 2019

What is the relationship between the Beat writers and music? How do you think that literary scene and musical sound connect(ed)?

I see that connection, as is well known, mainly in jazz and bebop (and Allen explicates those links – to ‘Howl’ in particular – in various interviews and annotated texts). The open vowels, the sibilant consonants, the varying degrees of quickness or languidness, all bring jazz and bebop to my mind…but this is no revelation!

As a writer or poet have you been shaped or influenced by Beat experiences?

Absolutely. In my younger days, I worked pretty hard to style myself after them, both the men and the women, both in attitude and work. When I was in college in Chicago, studying poetry with Paul Hoover, my best friend and I (also a poet) decided we’d create a two-girl Beat Generation. We did readings together, hung out at punk clubs (rather than jazz dives), and we even asked Allen, at a reading, if we could kidnap him so we could get on the cover of Time magazine. We thought that was a very Beat thing to do. Allen, of course, was into it, and gave us suggestions regarding who we could contact for publicity. Too bad we didn’t have a plan.

Which musical artists from whichever era appear to make links with the Beat Generation – and how?

I won’t even mention Dylan; that’s obvious. And Patti Smith. And the Grateful Dead (‘Cowboy Neal at the wheel of the bus . . .’ etc.). Jim Morrison’s lyrics were often equal parts William Blake, Allen, Celine, Rimbaud. Definitely Bowie, in his use of cut-ups, and then Burroughs interviewed him for Rolling Stone in 1974. And Burroughs also interviewed fellow wizard Jimmy Page for Crawdaddy in 1975.

Relatedly, Burroughs’s review of a Led Zep show for Crawdaddy the same year (I think?) continues to amuse, more so than the recently published 600+ page Zep bio which, honestly, I could’ve written myself just by recalling the articles I obsessively read in rock magazines as a teenager. WSB’s review ends with this oddly wholesome image of the audience during ‘Stairway’: ‘well-behaved and joyous, creating the atmosphere of a high school Christmas play.’

I still hold out hope that someday a rock god will look at me this way:

Who are your own favourite singers, musicians and bands? Do they represent Beat ideas or attitudes in their lives and art?

The ones just mentioned were formative to my attitudes, ideas, and work. The androgyny of Bowie – and Freddie Mercury, too, though I don’t connect him to Beatness; he was more 19th century – seemed like a Beat thing back then, though I don’t know why, really, now (I was mixed up!).

As a rock-and-poetry obsessed teen I wrote to Patti Smith regularly, through her fan club. For her birthday one year I photographed the houses she lived in when the Smiths lived in Chicago, and as a thank you she sent me an autographed copy of Babel.

And when she fell off the stage in (I think) 1977 I sent her a get well card with cartoon horses on it; she sent me a thank you note on Arista Records stationery, with a drawing of one of the cartoon horses. I think she was very aware of her young fans. Those little things were more talisman-like than she probably imagined. Actually, I’m sure she knew.

I saw a lot of correspondences with the punk bands and performers that I followed starting in ’74-75: that whole all-or-nothing attitude, the sacredness of experience, the willingness to follow a vision into darkness. Which makes me think of Springsteen. He fits, too.