Beat Soundtrack #17: Carl Spiby

In which prominent Beat figures, writers and critics, historians and academics, fans and followers, talk about the relationship between that literary community and music

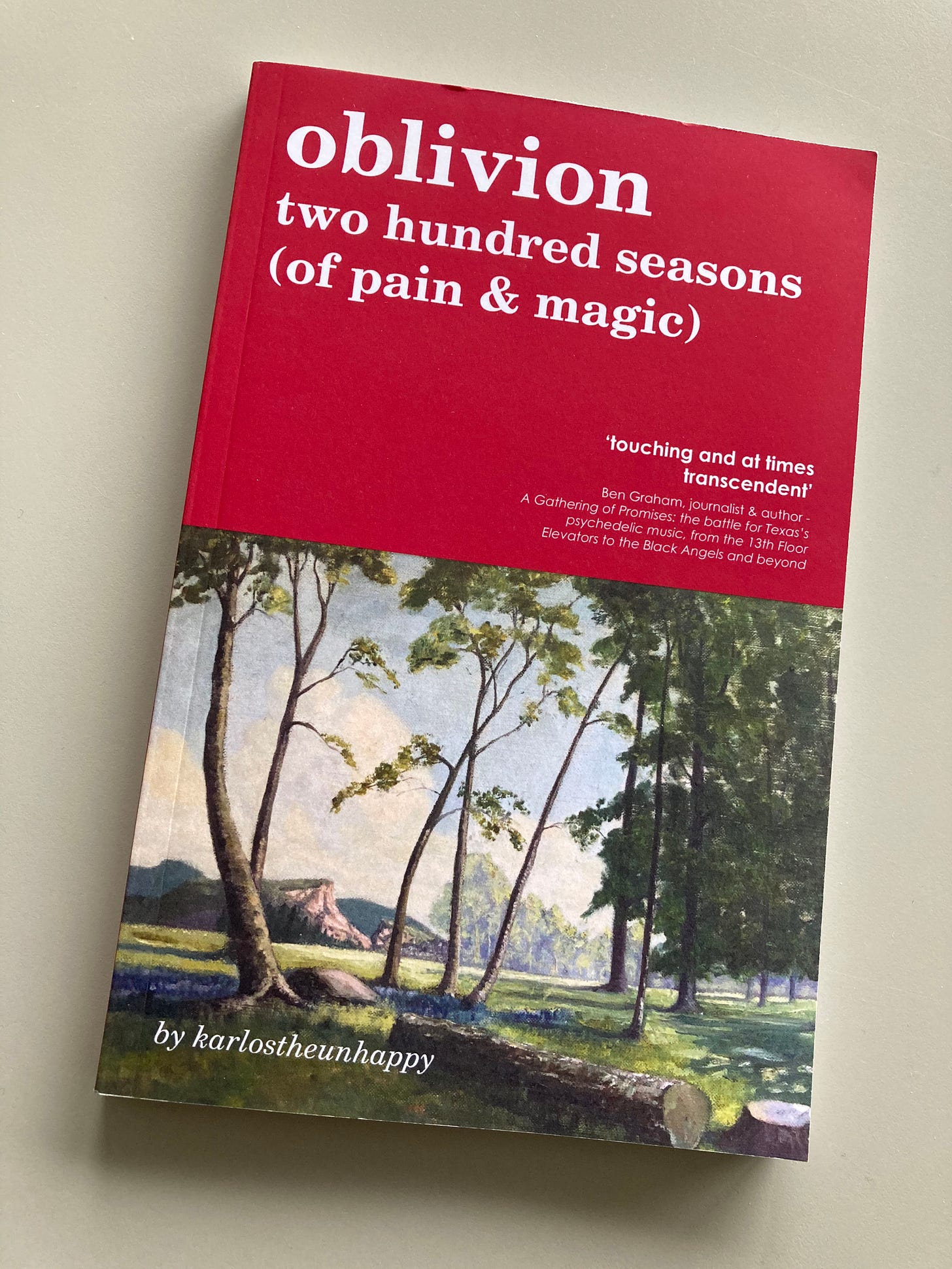

Poet Carl Spiby, who adopts the nom de plume karlsotheunhappy, is the author of Oblivion: Two Hundred Seasons (of Pain & Magic) (Gloomy for Pleasure, 2021), a collection which collates 30 years of writing in his distinctly British Beat style. In the 1990s, he was editor at the underground litzine Beat Surreal and, following his return to writing in 2020, was a finalist at that year’s Ledbury Poetry Festival slam. His lament for Jack Kerouac appeared in Beatdom #22, the Kerouac centenary edition. Oblivion was launched by the National Beat Poetry Foundation and he has performed at readings at Gloucestershire Poetry Society and Blackwell’s in Oxford, among others.

What attracted you to the Beats? When did you first encounter them? Are you drawn to a particular text, novel or poetry?

Just a council kid without a degree, who’d just dropped out of the Parachute Regiment before I got posted to Norther Ireland, I came to the Beats via a friend who returned from his humanities degree at what was then Brighton Polytechnic (now university) raving about Kafka, Kundera and Kerouac. Before the Beats, I was into surrealist writers like Paul Eluard and Jacques Prévert, not realising my copy of his Paroles was from Beat HQ at City Lights and their ‘Pocket Poets’ series.

Interestingly, there’s also that link there from automatic writing to spontaneous prose, surrealist games that lead to Burroughs’ cut-ups, which had also found its way into my life via a soundtrack of Bowie, who’d also famously used the same technique. And then the early San Francisco anarchist scene had spiritual links back to the surrealist and dada movement before the Beats as they were to become, having arrived from New York.

The Beats for me were transformative. As with the surrealists and Dadaists I was attracted to their sense of freedom, but also the Beats’ humanity (as opposed to their reputation built on pure hedonism), and massive scope. By scope I mean, in general, the fiction of Burroughs and, say, Kerouac or Gary Snyder is a million miles away from one other. The poetics less so. But also by scope I mean that, for example, from Kerouac you could jump off into Jack London, Matsuo Bashō, Thomas Wolfe, the Buddha, Walt Whitman, Christ, Proust or Thoreau.

Pictured above: Carl Spiby’s collection Oblivion (2021)

Having said that, having got the Beat rites of passage out the way (On the Road, ‘Howl’ and Naked Lunch), I would come to find that my favourite Beat writing was actually Jack’s Visions of Gerard and The Dharma Bums, Ferlinghetti’s Pictures of the Gone World, Brautigan’s In Watermelon Sugar. That’s if you’ll permit me to class Richard as a Beat, or post-Beat or whatever. Classification is probably the least exciting thing about the Beats, although I do get it: people merge the Beat Gen with the Beatniks as if one and the same thing.

Living so close to the Black Mountains, I also have a particular fondness to Ginsberg’s ‘Wales Visitation’. And here in Gloucestershire, with Michael Horovitz having lived not far away in the Slad Valley (where Laurie Lee also famously hailed from) near Stroud, I also have a soft spot for some of his work. Horovitz is important as he allows me to recognise an authentic Blakeian British Beat voice, rather than just the American Beat experience, and that, actually, the Beat tradition has roots here, thanks to Blake.

What is the relationship between the Beat writers and music? How do you think that literary scene and musical sound connect(ed)?

Jack is the greatest proponent of bop prose, with his jazz-influenced free flowing long sentences and kicking solo-like rhythm, the Beat oral tradition picking up where Rexroth was going. As Adrian Mitchell reminds us, in the introduction of his collection Love Songs of World War Three, all poetry comes originally from song. So I guess it is only natural that the era of Bird and Monk saw Jack re-establish the connection for his own age: the Beat Generation. His three albums are testament to this, and I am particularly fond of his 1959 album with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims.

Too often since then, jazz in spoken word is an accompaniment to a poetry performance, rather than an equal partner. Jack’s album sets the bar on how to deliver this kind of art in concert – by which I mean in tandem with equal weight – with the performer rather than have them merely provide backing.

Ferlinghetti’s ‘Autobiography’ is another favourite and good example, as are Kenneth Patchen’s albums. Again, Kenneth Rexroth is probably the grandfather of all this, but somehow it was Jack’s touch that perfected the scene for his time. It was, after all, the period of The Birth of the Cool (recorded 1949/50, sound of the Beat, but released in ’57 – peak Beat era).

Rolling forward, we see Jack’s influence on Dylan. Bob mixed that with the folk blues, fusing his own Beat-poet-style lyrics with that root heritage of Woody Guthrie.

As the next generation emerged, post-Beat and hippie, with the rise of bands like the Grateful Dead with its prankster psychedelics and ‘Further’, the Doors (aided at times by Michael McClure and so on) all evolved out of the Beats. Music evolved quickly with the rise of the teenager, just as the Beatles themselves evolved and precisely as Ginsberg evolved, Leary and Watts became household names and got kids, rock stars, poets and professors turned on and tuned in.

George Harrison has been a big influence on me, especially the early solo albums, but I also keep coming back to Kerouac and Gary Snyder. To me they started it all with their own exploration of the dharma. Music, of course, is a massive part of Indian culture, and I have to mention here that I am currently really enjoying Indian slide guitar music (like Debashish Bhattacharya): it’s a perfect listen whilst revisiting, say, Jack’s Scripture of the Golden Eternity or Some of the Dharma.

As a writer have you been you shaped or influenced by Beat experiences?

My collection Oblivion: Two Hundred Seasons (of Pain and Magic) gathers three decades of my writing, most of which is written with my peculiarly British Beat sensibility. I’m not from 50s USA. It’d be insincere of me to pretend otherwise. So, as I say, Horovitz is key here. His Albert Hall event connected the Beats to Britain and Blake and revealed through his own work and that of Trocchi and Adrian Mitchell et al that there was a vibrant British scene.

But I can’t shake the sense of enlightenment I get from the Beats. An atheist for much of my life, revisiting my own poems in Oblivion, most of which were written in the early to mid-1990s when I had an underground litzine called Beat Surreal, caused me to recognise the effect Jack’s exploration of Buddhism had on me. That, triangulated with George Harrison’s music, alongside re-reading of Ginsberg, Snyder, Whalen, Welch as well as Alan Watts and Ram Dass, to come together and complement this outlook and, along the way, influenced my writing directly.

I favour Jack’s view of the Beat Generation with focus on beatitude. The beatitude is too often overlooked. A couple of great titles bring it back to focus, in my humble opinion: Rob Sean Wilson’s Beat Attitudes: On the Roads to Beatitude for Post-Beat Writers, Dharma Bums and Cultural-Political Activists and Carole Tonkinson’s Big Sky Mind: Buddhism and the Beat Generation.

Buddhism is the religion of no religion. And I’m happy for Jack to have his personal God as he rediscovered at the end of The Dharma Bums and in Desolation Angels if not throughout his work on a more subtle level. His journey is his personal adventure on this road called life, a tragic yet enlightening and uplifting adventure. I think that journey plays a part in his perpetual relevance.

Which musical artists from whichever era appear to make links with the Beat Generation – and how?

Exploring the question more personally, I guess I see the influence of the Beats in many areas. For example, one of the things I’m listening to over an over right now is the soundtrack by Yo La Tengo to the fantastic Kelly Reichardt movie Old Joy (originally from a short story by Jonathan Raymond) from 2006.

Old Joy is very Dharma Bums/Desolation Angels-era-like Kerouac, in my opinion. It’s also a very honest look at friendship and the nature of change in friendship, just like On the Road is. I’m not a fan of the recent Kerouac movie adaptations and I think this does a better job by not being an adaptation yet touching on similar themes. It feels Beat without being ‘Beat’. Anyways, the music is perfect and sounds like a journey through the Big Sky country of Montana, as if we were driving out to Brautigan’s ranch there, or tracking up the Cascades with Snyder (It’s actually set east of Oregon).

Other times I hear the Beat and post-Beat sensibility in things like the Kinks’ early 70s albums or tracks like ‘Green River’ by Creedence Clearwater Revival which kicks along like the theme for hopping the midnight special, opening up the throttle on an Easy Rider chopper, or Cassady bouncing along as he works up through the gears in ‘Further’. Some songs just trigger mind movies that don’t actually have formal connections at all but release the warm jets by your own associations. As lovers of the Beat mind, these songs tap into new Beat mind movies. Well, they do for me.

Then there’s Morphine’s tragically few albums which invoke the spirit of the Beats as much, in my opinion, as the output of Tom Waits. And Dana Colley’s work on the A Coney Island of the Mind album with Ferlinghetti is superb.

Or back to that Buddhist/Hindu influence with Ronu Majumdar’s album Hollow Bamboo with Ry Cooder and Jon Hassell. That’s the sound at top of Desolation Peak, or the sound between the breaking waves of Big Sur heard as music in the space between the breeze and the chasing surf.

But it is the softer bebops and ballads of Bird that will forever stay with me as the original soundtrack to the Beats. ‘The Gypsy’, ‘Bird of Paradise’ (for which I always think of Dr Sax and rain on the streets of Lowell) or ‘Out of Nowhere’.

Who are your own favourite singers, musicians and bands? Do they represent Beat ideas or attitudes in their lives and art?

Like many of those you’ve interviewed, I’m sure, the topics of Barry Miles’ work seems to reflect a lot of our favourite bands. For me that includes Syd Barrett and early Floyd, the 60s underground and hippie scene as well as, of course, his array of Beat biographies. But that’s coincidence, not design. I also love the music of Nick Drake, Robert Wyatt’s perfect album of poetry in Dondestan and the unloved, tragic band that was Acetone (such incredible guitar work, such a sad end). In jazz I come back to Charlie Parker again and again, but also John Coltrane, the natural successor to Bird, I would claim. I wonder what Jack thought of ‘Trane? ‘Alabama’ still moves me to tears.

Separately, I’ve got a lot of time for Rozi Plain, This is the Kit, Starfucker, Angel Olson and Chet Baker and George Harrison remains a favourite and just keeps on giving.

Music is vital to my life. And I’ve yet to meet anyone who has enjoyed the Beat writers who isn’t also really into their music. We’re a breed. You can catch my playlist for Oblivion on Spotify and listed at the rear of the book. All my music is a long playlist for my entire life, my own music history. You can hear in it when I discovered the Beats just as you can hear when I first danced along to ‘Superstition’ by Stevie Wonder in my sister’s bedroom, singing along with a hairbrush mike. And I just keep adding classic tracks such as all that Indian slide guitar. The world of music is so rich, I’m not sure how I’d cope without it…

Note: Find out more here – facebook.com\karlostheunhappy – and visit the Oblivion playlist on Spotify…