Beat Soundtrack #23: Gottfried Distl

In which prominent Beat figures, writers and critics, historians and academics, fans and followers, talk about the relationship between that literary community and music

Gottfried Distl is an Austrian-born author and multimedia artist whose works are available via Amazon and YouTube. He started out in the 1970s inspired by the American Beat Generation with his body poetry in the aftermath of Viennese Actionism.

In the 1980s he joined the German new wave/art pop movement with his provocative Beat songs and wrote the hard boiled novels Europe to the Africans and Ice Golem: A Hot Adventure with a Cool Monster. The Limit of Songs is the first English-language edition of his lyrics and poems written between 1975 and 2011. Distl is also a pop journalist and worked as a Hollywood reporter for many years.

What attracted you to the Beats? When did you first encounter them? Do you have a favourite text, novel or poetry?

I grew up in Austria in the 1960s and at that time nobody in Arnold Schwarzenegger’s German-speaking home country cared about the American Beat Generation. The word ‘beat’ came into my life in 1964 when I was ten years old and that of course was the right age and moment in history to become a one hundred percent Beatles fan. From then on my life was all about ‘Yeah Yeah Yeah’ and the latest records by all the other great beat groups who sent rock & roll on the way up in search of excellence.

But there was something else: Bob Dylan. His voice sounded, one critic said, as if a madman was crying out loud over the walls of an insane asylum. I could listen to him for hours but his Beat connection – where he got the ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ from – I only got later. As John Lennon said, Dylan’s magic lies in his voice. It doesn’t matter so much what he’s saying; it’s how he’s singing it.

And here we have the magic of the Beats as I see it: it’s their ‘voice’ turning you on with their energy and their ecstasy. And that’s why I wanted to be a Beat writer when I got the idea of becoming a poet. I wanted everybody to shake, rattle & roll with my words.

There were only four Beat poets in Vienna in the early 1970s: Peter Hacker, Peter Gach, Christian Ide Hintze and me, Gottfried Distl. And what did it mean to be a Beat poet? With Peter Hacker I got drunk or high on LSD and we shouted at each other: ‘I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness!’ We didn’t want to be normal and live a normal life with a family and a dour job.

That’s why we got on the road like Jack Kerouac. That’s why we took drugs like Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs on their yage letters trip. And that’s why we felt like cool outlaws when we visited our friend Peter Gach in prison when he got busted because of his marijuana habit. And that’s why I created my body poetry in the 1970s where I attacked people on the street and in cafes with my body language. They ran away in fear.

I wanted to see action as a poet like Rimbaud and all those other ‘angelheaded hipsters’. And my late great poet friend Christian Ide Hintze founded the Vienna Poetry School in the 1980s with a little help from Allen Ginsberg. And when I got the chance to meet my hero the Beat poet Ed Sanders there, Ide Hintze said to him about me: ‘He was a wild man in the 1970s’. And I said to Ed Sanders: ‘I was a wild man thanks to men like you!’

Pictured above: Ed Sanders with Gottfried Distl

What is the relationship between the Beat writers and music? How do you think that literary scene and musical sound connect(ed)?

In Jack Kerouac’s On the Road it connected like this: ‘We went back to Frankie and the kids. Suddenly Dean got mad at a record little Janet was playing and broke it over his knee: it was a hillbilly record. There was an early Dizzy Gillespie there that he valued – “Congo Blues” – with Max West on drums. I’d given it to Janet before, and I told her as she wept to take it and break it over Dean’s head. She went over and did so.’ Destroy what you hate and destroy what you love. Don’t be afraid; that’s what Kerouac tells us here.

When the Who’s Pete Townshend destroys his beloved guitar, that’s Beat! That’s how the literary scene and musical sound connect. Pete Townshend is typical of this new generation of post-Beats: he is a writer and a musician. Just like Lou Reed. Lou Reed wasn’t afraid to destroy and to love and to destroy what he loves and to love what he destroyed. On the other hand, one of my favourite writers of all time Richard Brautigan turned literature into beat music. I always felt that he wrote like the beat music of the early Sixties sounded. He looked like a Beatle and he wrote like a Beatle.

Pictured above: Pete Townshend and Gottfried Distl

As a writer and journalist have you been shaped or influenced by Beat experiences?

As a writer and multimedia artist I fought from the underground in a mainstream world without any compromise. There’s a radio show with my literary and musical work from 1984, a subversive programme aired on Ö3, Austria’s biggest mainstream pop radio station.

You can listen to on YouTube. I am reading a Beat story I wrote about the Viennese 1970s hardcore underground scene of which I was a part, with 1980s German new wave/art pop music I recorded with my partner in crime Andrea Dee.

Then there’s my Beat poetry-inspired English-language book of lyrics and poems The Limit of Songs. And, in 1982, I made a new wave Super 8 experimental film with Andrea Dee in Vienna called Beat: A Bebop Fantasy in which youngsters from the city’s punk and new wave underground scene played the stars of the American Beat Generation as they imagined how it might have felt if you were one of those wild ones in the 1950s on your way from New York to San Francisco.

Famous Austrian actor Johannes Silberschneider played Jack Kerouac. The film is available on DVD in the German-language but can be delivered with an English translation.

As a pop journalist I come from the new journalism tradition of Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson and those great writers of the classic Rolling Stone magazine. And there has always been a bit of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine in me.

Which musical artists from whichever era appear to make links with the Beat Generation – and how?

Of course, Bob Dylan visited Jack Kerouac’s grave with Allen Ginsberg and who said that it’s a great loss that nobody writes like Ginsberg anymore. John Lennon met Allen Ginsberg many times – one time he opened the hotel room door standing there naked – in front of John’s wife Cynthia. Paul McCartney even played guitar for Ginsberg, who saw the Beatles as angels and was in the studio when the Rolling Stones recorded ‘We Love You’ with John and Paul.

Then there’s a man I always loved but sadly became some kind of joke in his own country: Donovan. He wrote some great Beat songs like ‘The Trip’. I met him a few times and he always talks about Jack Kerouac and how the Beat writers changed his life.

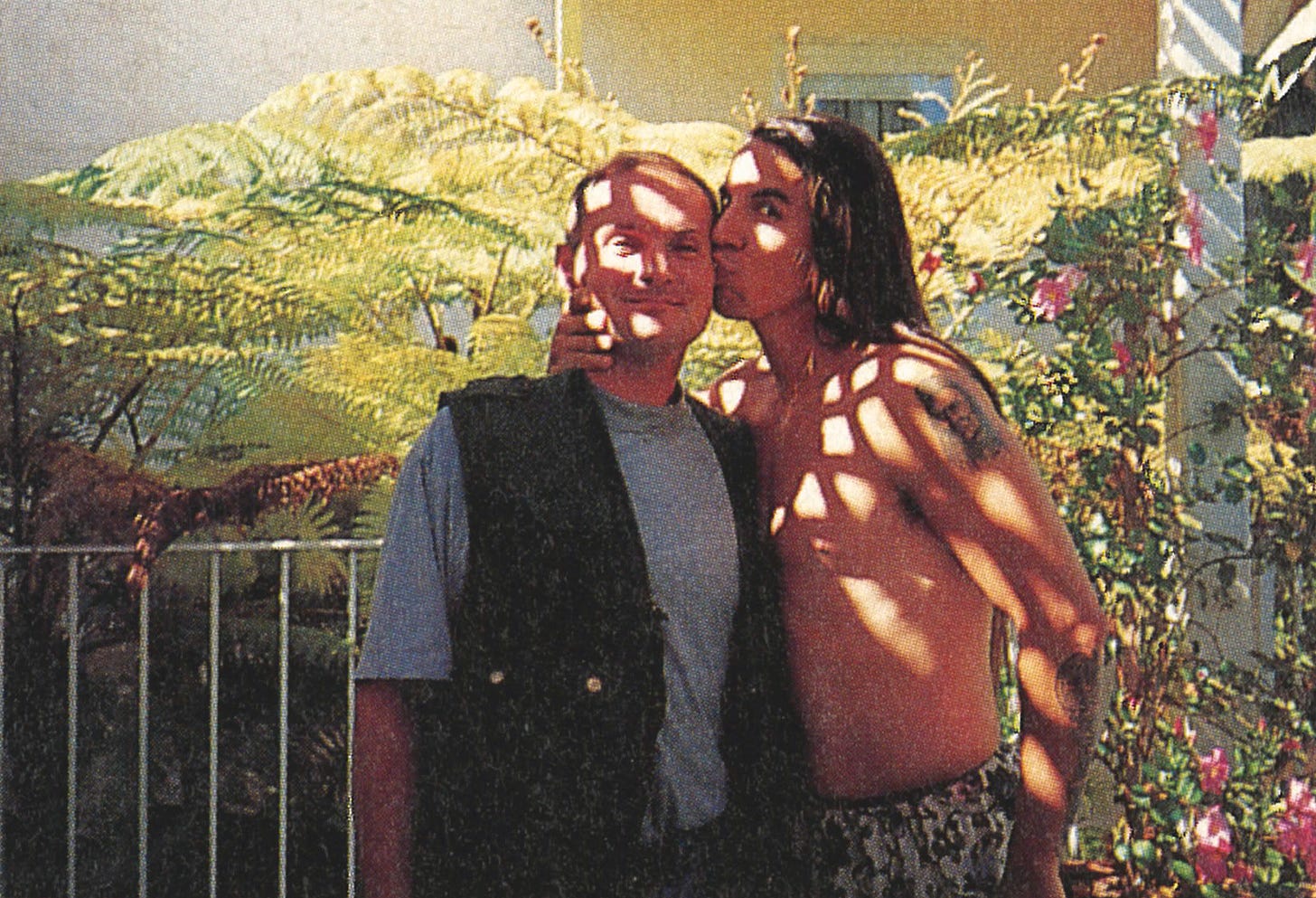

Then another forgotten record: ‘Le Beatnik’, a song recorded in London in 1966 by the French singer Michel Polnareff with Jimmy Page, of the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin, on guitar. And when I met the Red Hot Chili Peppers singer Anthony Kiedis in Los Angeles, he told me how he loved Jim Morrison and, with the Doors singer of course, we have the Michael McClure Beat connection. On the other hand, you find William S. Burroughs reading ‘What Keeps Mankind Alive’ on a Bert Brecht/Kurt Weill tribute album.

Pictured above: Gottfried Distl and Anthony Kiedis

Who are your own favourite singers, musicians and bands? Do they represent Beat ideas or attitudes in their lives and art?

I’ve already mentioned Bob Dylan, Lou Reed and Pete Townshend, the Fugs’ Ed Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg. Donovan’s Beat Zen lifestyle and his album Sutras. And Allen Ginsberg’s William Blake album I have always loved. It’s amazing how the poet and his musicians so congenially put music to Blake’s words.