Beat Soundtrack #28: Jim Cohn

In which prominent Beat figures, writers and critics, historians and academics, fans and followers, talk about the relationship between that literary community and music

Poet, writer, recording artist, editor, publisher, and poetics curator Jim Cohn was born in Highland Park, Illinois, in 1953. After his family moved to Cleveland in 1966, he graduated from Shaker Heights High School in 1971. With a year’s study at Hebrew University in Jerusalem (1974-1975) Cohn received a BA in English from the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1976.

After taking a poetics class with Anne Waldman that spring, Cohn later received a Certificate of Poetics from Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in 1980 where he studied with renowned Black Mountain, Beat Generation, New York School, Black Arts, Feminist, and Environmental Justice poets.

As a teaching assistant to Allen Ginsberg, he was introduced to a circle of Postbeat poets he would associate with for the rest of his life. It was also during this period that he began to investigate the poetics of sign language. From 1982-1984, he studied American Sign Language in the Interpreter Training Program at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID).

In February 1984, Cohn arranged a ‘Deaf-Beat Summit’ with Ginsberg and famed Deaf poet Robert Panara at NTID. In 1986, he completed his MSE in English and Deaf Education from NTID and the University of Rochester. In 1987, he coordinated the first National Deaf Poetry Conference in the United States.

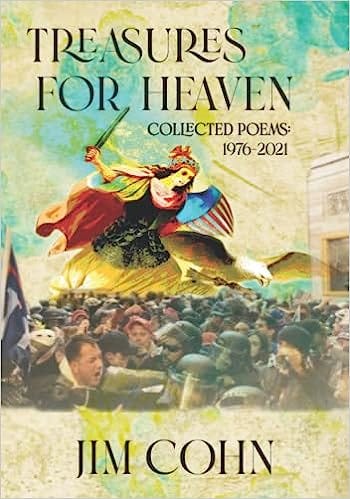

Pictured above: Cohn’s collected works were published in 2022

From 1988-1992, Cohn was a member of Birdsfoot Farm, an organic farming intentional community outside Canton, New York, near where he worked as a Disability Specialist at St. Lawrence University. He continued his vocation as a Disability Specialist at the University of Colorado in Boulder from 1997-2009, working with students with non-visible disabilities, and becoming an advocate for Disability Studies.

In 1998, Cohn founded the online Museum of American Poetics (MAP, poetspath.com), a virtual museum dedicated to poetics diversity and documented in its evolution by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Besides books of poetry and poetics nonfiction, spoken word recordings, and curating the vast MAP website, Cohn was a small press publisher and editor of poetry and poetics for three decades.

He mimeo-produced ACTION Magazine in the mid-1980s while living in Rochester, NY. From 1990-2015, he edited and published the annual poetics journal Napalm Health Spa (NHS). The final three issues of NHS were special editions: ‘Long Poems of The Postbeats’ (2013), ‘Heart Sons and Heart Daughters Of Allen Ginsberg’ (2014) and ‘Anne Waldman: Keeping The World Safe For Poetry’ (2015).

Cohn’s literary papers are archived at the University of Michigan Special Collections Library. In 2022, he published a collected edition of his own work from several decades: Treasures for Heaven: 1976-2021 (Giant Steps Press). He resides in Boulder County, Colorado, where his daughter, Isabella Grace Cohn, was born.

What attracted you to the Beats?

Initial attraction to the Beats had a lot to do with a sense that these poets and authors supported youth in their writing and activism. Ginsberg, in particular, passionately and viscerally decried the soulless, materialist, money-obsessed obscenity of American society and commemorated those who suffered from and railed against it. The Beats surely weren’t like my parents or anybody’s parents I knew. They spoke of bohemian things – sex, kicks, travel, psychedelics.

With perspicacious surrealist agency, Ginsberg attacked corporate greed, expansive militarism and oppressive government. Snyder became a celebrated figurehead of the Environmental Movement and spokesperson for the wild. Kerouac fostered the ‘rooksack rebellion’, and introduced Buddhist wisdom to young minds already wearied by a walls-closing-in mentality. The others major figures, Corso and Burroughs, they too spoke to youth, but of more phantasmagoric arcana, speculative and exotic matters, and with a less than clear political agenda.

The Beats weren’t denialists. They weren’t apologists. They were grounded, in their writing and their lives, in charting, chronicling and illuminating universal experience. Their work called for tolerance and compassion in an intolerant world. At times, they seemed like Shakespearean fools, wiser than any king. Other times they were like shamans and prophets. Still other times, some were strung out junkies and drunkards.

The Beats were visible to me, yes, as a mindful teenager stuck in the depressing provinces of Dullsville Midwest Great Lakes Americana 1960s at the intersections of the Anti-Vietnam War Movement and the humanist countercultural hippie movement with its ties to New Left political values, ecological activism, communal living, sexual revolution, mind-expansive hallucinogen tests, and work across US cities and campuses to take down lasting vestiges of entrenched institutional segregation.

They were engaged in spectacle-protest performance art and consciousness-raising activism of all kinds. Even back then, it wasn’t lost on me that Beat energy was part of an alternative and expansive literary tradition, a literary tradition that was sympathetic to labor and unions, to ecologists and progressives, to change-makers and fringe outcasts alike. The Beats, viewed holistically, were to me a proof that Whitmanic values remain fundamental to living in a Democracy.

When did you first encounter them?

My intersection with Beat Generation poets began when I took my first class with Anne Waldman, a class in poetics, at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics while simultaneously finishing my undergrad work in literature a few blocks away at CU-Boulder during the spring of 1976. After attending two Kerouac School summer writing programs, one in 1976 immediately upon graduation, and the other in 1978, I received a certificate of poetics in 1980 where I was one of several younger teaching assistants to Allen Ginsberg.

Except for Kerouac and Cassady, who were gone before Naropa opened its doors in 1972, I met up with many of the well-known Beat poets, and over the years since, have learned more about the greater Beat community that included a wide range of women of the Beat Generation, Beat poets of color, spontaneously-arising Beat regional poetry scenes, and a network of artists, political activists and translators from around the world.

Do you have a favourite text, novel or poetry?

Since the publication of my collected poems, Treasures for Heaven, in mid-2022, I wanted to rediscover Kerouac and to see how his spontaneous prose had weathered over the years and to contemplate his impact on the music I came up with. I was entering my seventh decade, noticeably weathered myself. Reading The Library of America edition of J.K.’s collected poetry gave me the pleasure of looking at Mexico City Blues, The Scripture of the Golden Eternity and Old Angel Midnight with new eyes/new mind. Each of these texts had been for me, as a younger artist, a meaningful bridge into Beat Generation aesthetics as well as Buddhist influences.

But what was also illuminating in going back was to review how bebop influenced Kerouac’s spontaneous writing style. To look again at Kerouac’s own writing manifestos as to how to develop spontaneity as a writing technique, be that on the page, spoken word or in conjunction with music, which was the heart of the matter of Beat differentiation from other literary groups before them.

For the first time in my life, I read Dharma Bums in late 2022. Pounded out in only eleven days, Dharma Bums loosely hangs together in scenes structured to produce a kind of novel form of narrative flow based on emotional highs and lows that was unique to Kerouac’s bebop influence. It’s a clear example of Kerouac’s notion of spontaneous prose. There was all the blowing of long solos. All the spontaneously written scenes. What stood out were the hefty doses of mood swings to suggest the possibility that Kerouac was consciously using potentially identifiable pathology as a plot development device. He was not building his text by any classic or traditional way or normative manner of novel building.

You weren’t going to get seamless transitions, logical or traditional beginnings, middles and ends. And it wasn’t the same as Burroughs’ cut-up methodology either. It was the sense of agency that comes directly out of bebop. The artistic agency to solo, riff, accompany and fill out a piece of music at will and based on different criteria than earlier manifestations of jazz provided. My favorite line in Dharma Bums is the Zen Buddhist saying that Snyder quotes to Kerouac as they’re climbing Matterhorn: ‘When you get to the top of a mountain, keep climbing’ (84). It’s this experience of climbing into the immaterial ether where Kerouac’s influence can best be understood.

I had a lot of questions about this Dharma Bums period of Jack’s life, roughly between 1956-1958; especially, around Kerouac and Snyder’s brief but critical friendship, and Kerouac’s reactivity as he began to crater on Desolation Peak, and then more so in the lead up to the publication of Bums. Kerouac was in an ambiguous and labyrinthian position of fictionalizing his new friend, Gary Snyder, into a larger-than-life cultural figure. It seems as though in creating the fictional Japhy Ryder, Kerouac became a kind of cursed Pygmalion-esque sculptor making an image of a mortal into a god without realizing that in the alchemy of doing so, his art would prove to be a double-edged sword that would destroy him. The book that has helped me most in interpreting Kerouac’s state of mind around this time period is Poets on the Peaks (2002) by John Suiter.

Whatever mental state was going on inside Jack Kerouac while a fire lookout on Desolation Peak, whatever introspective and/or moody places he went to and moody thoughts he had, part one of Desolation Angels has remained my favorite section among all Kerouac’s writing since reading it on LSD in the summer of 1972 for the way it inspired my own wilderness travels and allowed me to see and write about nature with nuance and grace. Alone in the wild, one is face-to-face with ego’s suffering and silence’s liberation. And this is also true in the lives of any number of musicians who succumbed to the downside of fame and fortune, another kind of ego wilderness – the wilds of the mind. When I think of Kerouac’s demise, I also think of any number of blues, jazz and rock and roll musicians who died too young.

What is the relationship between the Beat writers and music? How do you think that literary scene and musical sound connect(ed)?

First came the music. What young person, of any color or gender, seeking a liberationist perspective in American art from the mid-twentieth century onward could not see that bebop was the precipitating vehicle? Bebop hit like cubism before it – turning classical painting perspective on its head. You cannot overstate the importance of bebop as a social critique. The music and the musicians who made it marked a creative and intellectual breakthrough that would go on to impact the Civil Rights Movement, Black identity politics, mainstream progressive subjective consciousness, the arts, society and culture.

JoeThe music and the musicians were openly transmitting a new form of social justice. The players were no longer locked into sitting in an orchestra pit, reading a chart, playing a defined part and a defined part only. It wasn’t like Dizzy Gillespie was hired by a corporation to be just another wheel in the machine.

It was a celestial transmission. Bebop, with its concentration on disruption of the normative big-band rigidity, was known for extended improvisation and solos. Some thought of it as a revolution in terms of Black artistic freedom. Others saw it offering up Black political freedom. And still there were others who saw it as a way to Black economic freedom. Regardless of what form of freedom bebop represented, the music and players reflected a sophisticated intellectual alienation within jazz. And although that alienation was not new, the terms for it were. These were new musical dialogues between and among bebop’s practitioners as well as expressions, in music, of a new sense of narrative style and structure.

Everybody knows Ginsberg and Kerouac frequented after-hours basement jazz clubs of Greenwich Village and Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, considered to be the birthplace of bebop, absorbing the improvisational spirit of the musicians who performed there. It’s not difficult to see why they frequented these venues. The stylistic parallels between bebop and the Beats are clear: stream-of-consciousness poetry mirroring freely improvised solos like Charlie Parker’s ecstatic melody lines on the alto saxophone or Thelonious Monk’s angular dissonances, percussive attacks, hesitations and silences on the piano.

As for John Coltrane, his explorations in harmonic progression variation, known as the ‘Coltrane Matrix’, are well documented as is his development of high-speed arpeggios and the scale patterned ‘sheets of sound’ improvisation style heard on Giant Steps, regarded as one of the most influential jazz albums of all time. Understandably, music made by one definition of a counterculture that flew in the face of the social and musical establishment resonated deeply with the Beat Generation in their break away from literary conservatism.

Allen Ginsberg said that ‘Howl'‘ was inspired directly by tenor sax great Lester Young’s classic ‘Lester Leaps In’, which Ginsberg became aware of through Kerouac’s influence. Kerouac’s On the Road is said to have taken direct inspiration from Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray’s 1947 blowing session ‘The Hunt’. Early Beat Generation Black poets including Amiri Baraka, Ted Joans and Bob Kaufman also demonstrated radical new techniques and practices that changed the formal and narrative structures and style of poetry based on the bebop revolution. And in many instances, as we know too well, many of the greatest of these artists’ taste for heroin, Benzedrine and other drugs led to early deaths.

Kerouac’s ‘Essentials of Spontaneous Prose' remains one of the best documents to understanding what aesthetic transmissions were being drawn from bebop and applied to Beat poetics. Spontaneity was the fundamental notion, the fundamental practice, that Kerouac embraced and borrowed from bebop and applied to his own experimental writing style. In terms of procedures on how to open one’s self to literary composition, Kerouac clearly was influenced by bebop when he wrote, ‘Time being of the essence in the purity of speech, sketching language is undisturbed flow from the mind of personal secret idea-words, blowing (as per jazz musician) on subject of image.’ In terms of method, Kerouac advocated ‘No periods separating sentence-structures already arbitrarily riddled by false colons and timid usually needless commas—but the vigorous space dash separating rhetorical breathing (as jazz musician drawing breath between outblown phrases)—“measured pauses which are the essentials of our speech”—“divisions of the sounds we hear”—“time and how to note it down” (William Carlos Williams).’

When considering scope, Kerouac suggested ‘Not “selectivity” of expression but following free deviation (association) of mind into limitless blow-on-subject seas of thought. […] Blow as deep as you want.’ Then, Kerouac says this about developing a center of interest: ‘Begin not from preconceived idea of what to say about image but from jewel center of interest in subject of image at moment of writing, and write outwards. […] Never afterthink to “improve” or defray impressions, as, the best writing is always the most painful personal wrung-out tossed from cradle warm protective mind.’

What Kerouac says next, about structure of work, is most telling of how his sense of ‘Deep Form’ in prose was derived from bebop’s scrutiny, invention and break from traditional big-band jazz musical form and structure. About narrative structure, he writes, ‘Follow roughly outlines in outfanning movement over subject […] arriving at pivot, where what was dim-formed “beginning” becomes sharp-necessitating “ending” and language shortens in race to wire of time-race of work, following laws of Deep Form, to conclusion, last words.’

As to one’s mental state while composing prose and/or verse, Kerouac concludes his ‘Essentials of Spontaneous Prose’ like this: ‘If possible write “without consciousness” in semitrance (as Yeats’ later “trance writing”) allowing subconscious to admit in own uninhibited interesting necessary and so “modern” language what conscious art would censor, and write excitedly, swiftly, with writing-or-typing-cramps.’

As a poet, writer and musician have you been shaped or influenced by Beat experiences?

If, by ‘Beat experiences’, you are asking me, ‘Did I adopt and transmit to others through my poetry, nonfiction prose poetics and recordings a sense of personal release, purification, and illumination through the heightened sensory awareness that might be induced by drugs, music, sex, or practices related to Buddhism’, the short answer is yes. If you’re asking me, ‘Was my life as a poet such that, like the Beats and their advocates, I felt the joylessness and purposelessness of modern polarized, disinformed, bot-brained, gun-mad, domestic terrorizing society sufficient justification for both withdrawal and protest’, I would again answer in the affirmative. And if by ‘Beat experiences’, you are asking me, ‘Was my verse frequently chaotic and liberally sprinkled with non-duality consciousness – or what is also referred to in Buddhism as nonduality bias – intended to liberate poetry, the poet and the reader from academic preciosity, the dysfunctional normative-based mental health state, the ever-growing military-industrial carbon-junky state’, I would again answer yes.

But if you’re asking me, ‘Is my Treasures for Heaven: Collected Poems 1976-2021 an embodiment of the “Beat experience” only?’, I’d answer no. And that is the answer your readers and associates, I would imagine, would assume in the Postbeat era. I wasn’t contained by Beat influence only, but in conjunction with other developments and movements within the greater poetry as well as music world. I didn’t allow myself to write only in one style or in any signature way. For me, there was the Black Arts Movement and the various poetry communities of color to consider, Feminist and Women’s Poetry Movement works to explore, works coming out of LGBTQIA+ communities, as well as Deaf, Deaf-Blind and Disability poetry communities from which to deepen one’s sense of the import of signs and the signing space, accessibility, and to understand the oppressive history of normative pathological stigmatization foisted onto Disability communities.

For me, it was imperative to create something that was of my time and my world. My poetry took the ‘Beat experience’ further, just like the Rolling Stones took me further as a kid with ‘2000 Lightyears from Home’ (1967). Take, for example, this little number:

Aboard The Starship Howl

Your spirit embarks

On a perilous journey,

The lodge of the cosmos

Calling your name.

A flying log cabin,

Your heart resides there.

Nothing you lack.

Space knows no fear.

Your wandering spirit,

That welcomes each & all,

Never turns a cold shoulder.

Avoid not the dark door.

Roll beyond any sovereign,

Past grim gothic galaxies,

Vistas of nowhere

That join mind & wind.

O torchbearer of the future,

Daughter of rosewater,

Son of none,

I see myself in you

Searching the torn luggage of asteroids,

Eons of empires in disarray.

Assumptions driven by the past

Cannot save what’s already lost.

Victims of wars

Beacon countenance of stars.

Wild is the universe.

Forever wild are you.

Cloaked in language,

Bonded by fire & all that’s invisible,

In the hunger strike of emptiness

The bounty is without end.

Untethered battlefields

Float in weightless quintessence.

Despite these cosmic battles,

We came in peace,

Past radiant green hats

& umbrellas of rock,

Cognac smelling ice orbs

Stumbling drunk thru light.

You’re captain & crew,

Singular––complete,

Breathing in poison.

Breathing out nectar.

Hoboken, New Jersey

21 January 2019

We live in a much different world today, a much more interconnected and crisis-bearing world, with problems that the Beats could only warn us were coming, which they did, and they were not wrong. America is rife with disinformation and misinformation, politically-charged dueling media realities over facts, conspiracy theories, polarized versions of news, racism, sexism, antisemitism, islamophobia, economic inflation, loss of women’s reproductive rights, religious extremism, a supreme court disregarding the rule of legal precedent, climate change crises demanding mass-cooperation, endless streams of uprooted and homeless humanity at our borders and on our streets, pharmaceutical and illicitly manufactured cheap synthetic opioids that are up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine and a major contributor to fatal and nonfatal overdoses, a major political party and a former president being direct threats to Democratic values framed in the Constitution, and if that were not enough, daily mass shootings – all the hallmarks of white supremacy and the rise of autocracies.

Which musical artists from whichever era appear to make links with the Beat Generation – and how?

One of the impacts of the Beat Generation was the general lifting up of pop music to a high art form worthy of serious criticism and analysis. Of course, it helped that pop artists were gaining control over their songwriting as well as their own records, and that lyrics were far more substantial in meaning and complexity. Ginsberg was so impressed, and not without jealousy, over the fact that most young people knew the words to popular songs, but few could recite from memory any of his poetry.

Allen understood the power and reach the most popular recording artists of the 1960s had to sway youth opinion and it was his intention to mobilize as many of us as he possibly could. In his mid-1960s Iron Curtain travels to the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Cuba at the height of the Cold War, Ginsberg carried three albums with him wherever he went: the Beatles, Bob Dylan and Ray Charles. These were the sounds of freedom he shared with poets and writers from communist countries.

The flagship band to grow directly out of the Beat Generation was the Fugs, a satirical New York City underground rock band that formed around 1964. One of the group’s founding members, Ed Sanders, himself a political poet and activist, investigative scholar and musician closely associated with the Beats, became a key elder Beat poet in the transitional Postbeat period. A latter-joining member of the Fugs, Steven Taylor, was a long-time Ginsberg music collaborator and is himself a composer, songwriter and guitarist. The Fugs were a direct bi-product of Sanders’ close relationship to the Beat Generation.

Coming together in 1965, with a devoted fan base that would develop across the nation over the decades, the Grateful Dead made its own deep and lasting connections to the Beats. It’s impossible to not see the link between Kerouac’s On the Road and the Dead’s ‘Truckin'’ with its line ‘Get out of the door – light out and look all around’ similar in sentiment to Kerouac’s ‘There was nowhere to go but everywhere.’ The Dead’s song ‘The Other One’ offers these lines that memorialize Neal Cassady in his reinvention from Beat icon to Merry Prankster: ‘There was cowboy Neal / at the wheel / of a bus to never-ever land’. Recently, I’ve also noticed that the Dead’s version of Bonnie Dobson’s ‘Morning Dew’, a song about nuclear annihilation, ends with the line ‘I guess it doesn’t matter anyway’ which is very similar to this line Kerouac wrote atop Desolation Peak: ‘I don't know, I don't care, and it doesn't make any difference.’

How could the Grateful Dead have established itself as an improvisational ‘jam band’ without the precedent of bebop’s greats? Recently, I saw an interview with Bob Weir (CBS News, November 27th, 2022, online) who at 75 years old continues to perform songs from the Grateful Dead catalog. In a discussion of how he is moving the songs into a new and expansive framework – with an orchestra – he talked about the characters within the Dead’s catalog. Weir said that the characters in the songs of the Grateful Dead ask of him to have their stories told. Listening to Weir’s discussion on these songs needing to be heard, I thought to myself, ‘This is how a song has its own life – separate and beyond the singer, songwriter and the band.’

The most significant poetic figure influenced by the Beats and their ethos, for me, is Bob Dylan whose enchantment with Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues early in his musical career led to a long friendship with Allen Ginsberg. I read anything serious that comes out about Dylan, and historian Sean Wilentz’s Bob Dylan in America provides the best treatment regarding Dylan’s relationship with the Beats in the chapter ‘Penetrating Aether: The Beat Generation and Allen Ginsberg’s America’. I’ll add that sometimes Dylanologists fudge on Dylan’s association with the Beats, as Harvard professor Richard Thomas did in his otherwise brilliant Why Bob Dylan Matters (150-151).

I don’t think you can discount any of the following musical artists not already mentioned for their own connection to the Beats, primarily via Kerouac, Ginsberg or William S. Burroughs: Laurie Anderson, Bono, David Bowie, Jim Carroll, Kurt Cobain, Mick Jagger, Rickie Lee Jones, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Joni Mitchell (through her association with Trungpa Rinpoche, Naropa’s founder and Allen Ginsberg’s Buddhist teacher), Jim Morrison, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Joe Strummer and Tom Waits.

Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs all left discographies for future listeners. The Kerouac discography includes Readings by Jack Kerouac On The Beat Generation (1960), The Jack Kerouac Collection (1990), The Complete Jack Kerouac Vol. 1 (2018) and The Complete Jack Kerouac Vol. 2 (2018). The Ginsberg discography includes William Blake – Songs of Innocence and Experience (1970), Holy Soul Jellyroll (1972), First Blues: Rags, Ballads & Harmonium Songs (1981) and The Lion For Real (1989). Burroughs’ discography includes Call Me Burroughs (1965), The Doctor Is On the Market (1986), Dead City Radio (1990), The ‘Priest’ They Called Him [with Kurt Cobain] (1993) and The Best Of William Burroughs (1998).

Of all the latter-day Beats who work with musicians, standouts for me are American poets Anne Waldman and Andy Clausen who each have impressive catalogs of spoken word poetry and music. Another US poet with an excellent band to back his impressive performance poetry is Paul Richmond. I’ll add that my own catalog of recordings offers an inherent and cumulative reference to the Beat Generation, as well as to the music of the Postbeat era, and is readily available online.

Who are your own favourite singers, musicians and bands? Do they represent Beat ideas or attitudes in their lives and art?

These days, I don’t think as much about my favorite singers, musicians or bands. We’re all only here temporarily. We’re here living our purpose. Trying to break through the cosmic glass ceiling of suffering. Trying to work out all this illusion. Trying to organize and publish back catalogs or selling them off. But when you’re gone, only the song remains. You can’t take it with you. Only the people die. The song remains. Today, I look for worth and meaning from the song itself. The song that refuses to die. The song that survives the singer.

It was in 1860 that Francis James Child published his eight-volume collection English and Scottish Ballads. It was extremely useful to my own sense of musicology to have studied the Child Ballads with Allen Ginsberg while still a student at the Kerouac School. Growing up with folk music, the Child Ballads demonstrated to me how a song grows and changes over time. The ballads Child favored for his collection are the dark and creepy stories. No doubt the reason for this preference lies with something I learned from Deaf poets who approach their performance art without any written text. If you’re a poet performing your poems in American Sign Language from memory, they best be memorable in the first place. This is also the case, as one would expect overall, from the ballad tradition.

Child assembled his chosen ballads based on motifs and those motifs remain highly inclusive of most of the craziness that goes on in this world we are only passing through:

‘romance, enchantment, devotion, determination, obsession, jealousy, forbidden love, insanity, hallucination, uncertainty of one's sanity, the ease with which the truth can be suppressed temporarily, supernatural experiences, supernatural deeds, half-human creatures, teenagers, family strife, the boldness of outlaws, abuse of authority, betting, lust, death, karma, punishment, sin, morality, vanity, folly, dignity, nobility, honor, loyalty, dishonor, riddles, historical events, omens, fate, trust, shock, deception, disguise, treachery, disappointment, revenge, violence, murder, cruelty, combat, courage, escape, exile, rescue, forgiveness, being tested, human weaknesses and folk heroes.’

It’s a pretty comprehensive list of human suffering that makes its way into song. The spectrum of hopes and fears. Child’s subject list contains a continuum of psycho-emotional states of being that result in human conditionality and human habituation. This is what made the ballad the premiere realm of the first noble truth in Buddhism: life is suffering.

One of the greatest ballads to come out of America is ‘Stagger Lee’, a crime-based folk song with variant titles and verses about ‘Stag’ Lee Shelton murdering Billy Lyons in St. Louis on Christmas night, 1895. The song has had numerous variant titles since it was first published in 1911 and first recorded in 1923 by Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians, titled ‘Stack O' Lee Blues’. One hundred years old this year (2023), the following variants on the song’s title show how a song refuses to die while managing to survive many singers over many years: ‘Stack-a-Lee’ and ‘Stacker Lee’, ‘Stagolee’ and ‘Stagger Lee’, also ‘Stackerlee’, ‘Stack O'Lee’, ‘Stackolee’, ‘Stackalee’, ‘Stagerlee’ and ‘Stagalee’.

Perhaps there is no greater mythos surrounding any recording made in the United States than Robert Johnson’s 1937 release of ‘Cross Road Blues’. This is the song where the delta blues master supposedly sells his soul to the Devil in exchange for his musical talents. Elmore James recorded his version in 1954 and again in 1960-1961. Eric Clapton’s first version of the song, ‘Crossroads’, was recorded in early 1966 when he was still with John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, and then he recorded a second version with Cream later the same year.

In my own poetry, I referenced this kind of twisted and unpredictable path a song takes over time in a poem called ‘Bardo-by-the-Sea’. The poem illustrates how the Irving Berlin song ‘Blue Skies’, written in 1926, has made itself heard over time since first recorded by Josephine Baker in 1927:

Bardo-by-the-Sea

Purpose calls in sick to spend the day along the boardwalk at Bardo-by-the-Sea. She rides a mint green 50cc scooter to the beach, takes off her cranberry velvet toque and shakes down her long red hair. “Holy days, sun shining so bright,” she shouts, picking out Josephine Baker’s 1927 recording, ‘Blue Skies,’ coming from an open second floor window. Passing the Kimono Cafe, she hears the 1937 Maxine Sullivan cover drift out the door. An iridescent 1967 black GTO convertible slows––it’s Betty Hutton’s 1944 rendition playing on the radio. The song stops a baby’s crying. Tank top waif scours gutters in search of french fries as Ella Fitzgerald’s 1957 version fills the air. If that don’t beat all, Purpose finds a bundle of old jazz photographs tied with a green shoelace left in the sand––amazing coiffures, vests, shoes, jewelry, hats. A note taped to the top photo reads, ‘The negatives are hidden behind the dry wall.’

So, yes, the variant transformative aspects of the intergenerational song just thrills me no end. Old Growth Song Groves, because of their neither dead nor alive status, always remind me of Burroughs’ thought about language – as a virus from outer space. Maybe the universe, cosmos, galaxies, planets, stars and black holes are made not from either sentient or insensate matter, but of relics of songs and their stories. Remarkably, I might add, if you consider Bob Dylan’s live performance career, he has experimented nonstop in how a song might mutate over just one person’s years. For one of the most dramatic reframings of any song from my lifetime, consider Joni Mitchell’s original version of ‘Both Sides Now’ as a folk song in 1968 with her jazz orchestral version from 2000.

Here is just a microdose from the Shangri-La Motel where all these songs that have inspired me and my poetry live in some inexplicable mystical state of suspended hydrogen-powered jukebox animation. Songs that haunt me to this day. Songs that refuse to die. Songs that can’t be killed off, as the music critic Greil Marcus might say. Each, in its own way, reflects some aspect of Beat ethos.

Songs from the 1920s-1950s: Blind Willie McTell’s 1929 recording ‘Statesboro Blues’. Walter Vinson with The Mississippi Sheiks 1930 blues single ‘Sitting on Top of the World’. Holy Art Tatum’s 1933 masterful version of ‘Someone to Watch Over Me’. Billy Holiday’s 1939 version of ‘Strange Fruit’. Hank Williams as Luke the Drifter’s tips to know-it-alls in the 1951 talking blues ‘I’ve Been Down That Road Before’. Big Mama Thornton’s 1953 hit ‘Hound Dog’, about lazy men just looking for a woman to take care of them.

These two from 1955: Muddy Waters’ ‘Mannish Boy’ and Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’. Two tracks from 1956: Elvis Presley’s crossover remake of ‘Hound Dog’ and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ cult-classic ‘I Put a Spell on You’. Buddy Holly and the Crickets’ 1957 single ‘Not Fade Away’. Two from 1958: Ritchie Valens’ ‘La Bamba’ and Link Wray’s ‘Rumble’, the only instrumental record ever banned on US radio. Three major Beat releases from 1959: the film Pull My Daisy, directed by Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie, which opens to the classic Beat Generation tune ‘Pull My Daisy’ with lyrics credited to Kerouac and music by David Amram, and these two ultimate Beat audio recordings: Jack Kerouac & Steve Allen: Poetry for the Beat Generation and Allen Ginsberg Reads ‘Howl’ (Big Table, Chicago).

Songs from the 1960s: The Marvelettes’ 1961 release of ‘Please Mr. Postman’, Bo Diddley’s 1962 cover of the wise-beyond-words Willie Dixon tune ‘You Can’t Judge a Book by the Cover’. Jan and Dean’s 1963 street race gone awry cautionary tale ‘Dead Man’s Curve’, the first 45 record I ever owned. These three songs from 1964: Chuck Berry’s ‘Promised Land’, written while he was in prison, Sam Cooke’s Civil Rights classic ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’ and Bob Dylan’s ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’, a generally factual account of the killing of a 51-year-old Black barmaid, Hattie Carroll, by 24-year-old William Devereux ‘Billy’ Zantzinger [sic], a young man from a wealthy white tobacco farming family. The Beatles’ 1965 Buddhist ballad, ‘Nowhere Man’.

Three from 1966: The Yardbirds’ (with Jeff Beck) blues and psychedelic rock hit ‘Over Under Sideways Down’, Buffalo Springfield’s protest anthem ‘For What It’s Worth’ and Jimmy Ruffin’s ‘What Becomes of the Brokenhearted’. These three from 1967: Aretha Franklin’s feminist anthem ‘Respect’, the Doors’ ‘Light My Fire, featuring Jim Morrison, who’d studied poetry with the Beat-associated poet Jack Hirschman at UCLA, and James Carr’s soul classic ‘The Dark End of the Street’.

The Rolling Stones’ culturally subversive 1968 (US) release of ‘Street Fighting Man’. Also from 1968: Otis Redding’s ‘I’ve Got Dreams to Remember’, Jimi Hendrix’s acid-fueled blues number ‘If 6 Was 9’, Phil Ochs’ ‘The War is Over’ and James Brown’s ‘Say it Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud’. From 1969: the Allman Brothers’ ‘Whipping Post’, Sandy Denny’s reflective ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes’; released on Fairport Convention’s stellar album Unhalfbricking, and John Lennon’s anti-war bed-in hit with Yoko Ono, ‘Give Peace a Chance’.

Songs from 1970-2000: Three from 1970: Nina Simone’s ‘To Be Young, Gifted and Black’, Santana’s cover of Tito Puente’s ‘Oye Como Va’ and Janis Joplin’s cover of ‘Me and Bobby McGee’, recorded only a few days before her death. Four from 1971: Marvin Gaye’s anti-police brutality, anti-violence hit ‘What’s Going On’ Gil Scott-Heron’s ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’, the Temptations’ ‘Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me)’ and Leon Russell’s ‘The Ballad of Mad Dogs & Englishmen’ from the Joe Cocker 1970 tour documentary Mad Dogs & Englishmen. Two from 1972: Stevie Wonder’s ‘Living in the City’ and Little Feat’s Sailin’ Shoes version of Lowell George’s ‘Willin’’. Paul Simon’s 1973 hit ‘American Tune’. Gram Parson and Emmylou Harris’ 1974 release on Grievous Angel of their cover of the Boudleaux Bryant 1960 hit for the Everly Brothers, ‘Love Hurts’. From 1975, Allen Ginsberg’s Rolling Thunder Revue song to Dylan, ‘Lay Down Yr Mountain’, which I produced for Ginsberg in his last recording session before his death in the summer of 1996. The Sex Pistols’ 1977 monster smash ‘God Save the Queen’. Neil Young’s 1979 ‘My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)’ from the Rust Never Sleeps album which features the line, ‘It’s better to burn out than to fade away’. Jim Carroll’s ‘People Who Died’, from his 1980 Catholic Boy album, a song whose lyric borrowed from Beat and New York School poet Ted Berrigan’s poem of the same name.

Michael Jackson’s 1983 release of the ‘Thriller’ music video, the first music video to be selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress (2009). Four from 1984: Leonard Cohen’s hymn-like gem ‘Hallelujah’, Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born in the USA’, Prince’s ‘Purple Rain’ and Tina Turner’s ‘What’s Love Got to Do with It’. Susanne Vega’s 1987 single ‘Luka’. Four from 1988: Tracy Chapman’s ‘Fast Car’, Willie Colon’s ‘El Gran Varon’, Patti Smith’s ‘People Have the Power’ and U2’s ‘Desire’. Two from 1989: Tom Petty’s ‘Runnin’ Down a Dream’ and Public Enemy’s ‘Fight the Power’.

Sinéad O’Conner’s 1990 anti-police violence song ‘Black Boys on Mopeds’. Three from 1991: Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’, Pearl Jam’s ‘Jeremy’, based on the true story of 15-year-old sophomore student Jeremy Wade Delle who on January 8th, 1991 walked into his English class at Richardson Texas High School and killed himself in front of 30 fellow pupils and their teacher, and Van Morrison’s beatific spoken word account of his youth – 1991’s ‘On Hyndford Street’, which mentions, among many things past, Kerouac’s Dharma Bums.

Whitney Houston’s 1992 knock out soul ballad arrangement of the Dolly Parton hit ‘I Will Always Love You’. Joni Mitchell’s 1994 ‘The Magdalene Laundries’’ a first-person account of a young girl incarcerated in one of Ireland’s notorious Magdalene institutions for the crime of being over twenty, unmarried and attractive. I’ll close out my playlist with Steve Earle’s 2000 ‘Transcendental Blues’ which opens with the drone of a harmonium always taking me back to Ginsberg.

See also: Correspondence #20: Jim Cohn, February 17th, 2023