Biographical Details #1: Jack Kerouac by Steve Turner

Writers writing about writers

A NEW SERIES for Rock and the Beat Generation as biographers, who have told the life stories of Beat authors and connected countercultural personalities or portrayed musicians who have become associated with that literary world, talk about the process involved in bringing their work from the drawing board to the bookstore, the computer keyboard to our own personal libraries.

To begin, the celebrated British music journalist and cultural historian STEVE TURNER discusses his widely-praised Jack Kerouac biography Angelheaded Hipster, published by Bloomsbury in 1996….

What is biography for?

For giving readers an accurate insight into a life. As a biographer you need to decide what the most important facts are in your subject’s life and order the information in a way that entertains, informs, and educates. My biography The Man Called Cash was originally to be based on something like 16-hours of interviews with him. He signed on the dotted line, but then died.

Initially I assumed that would be the end of the project but then I realised I could still write an authorised biography by talking to his family, friends, and colleagues – which is what I did.

It’s a mistake to think that autobiography is more accurate than biography because we deceive ourselves and our memories are both selective and distorted. In controversial areas I find it best to trust the accounts of three witnesses. One could be biased or vindictive. Two could be a collaboration. But three tends to be close to the truth.

What did you hope to achieve with your account here?

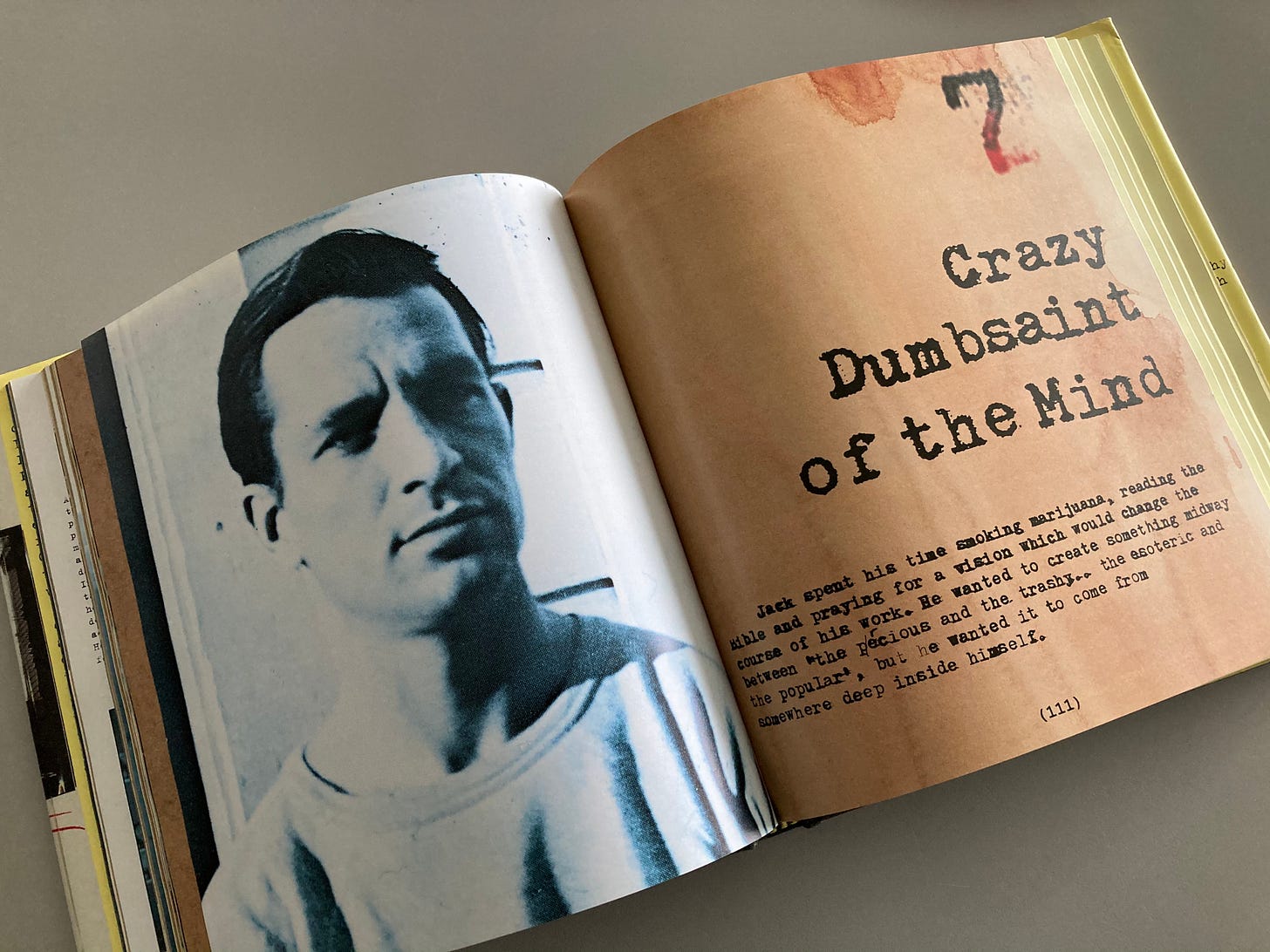

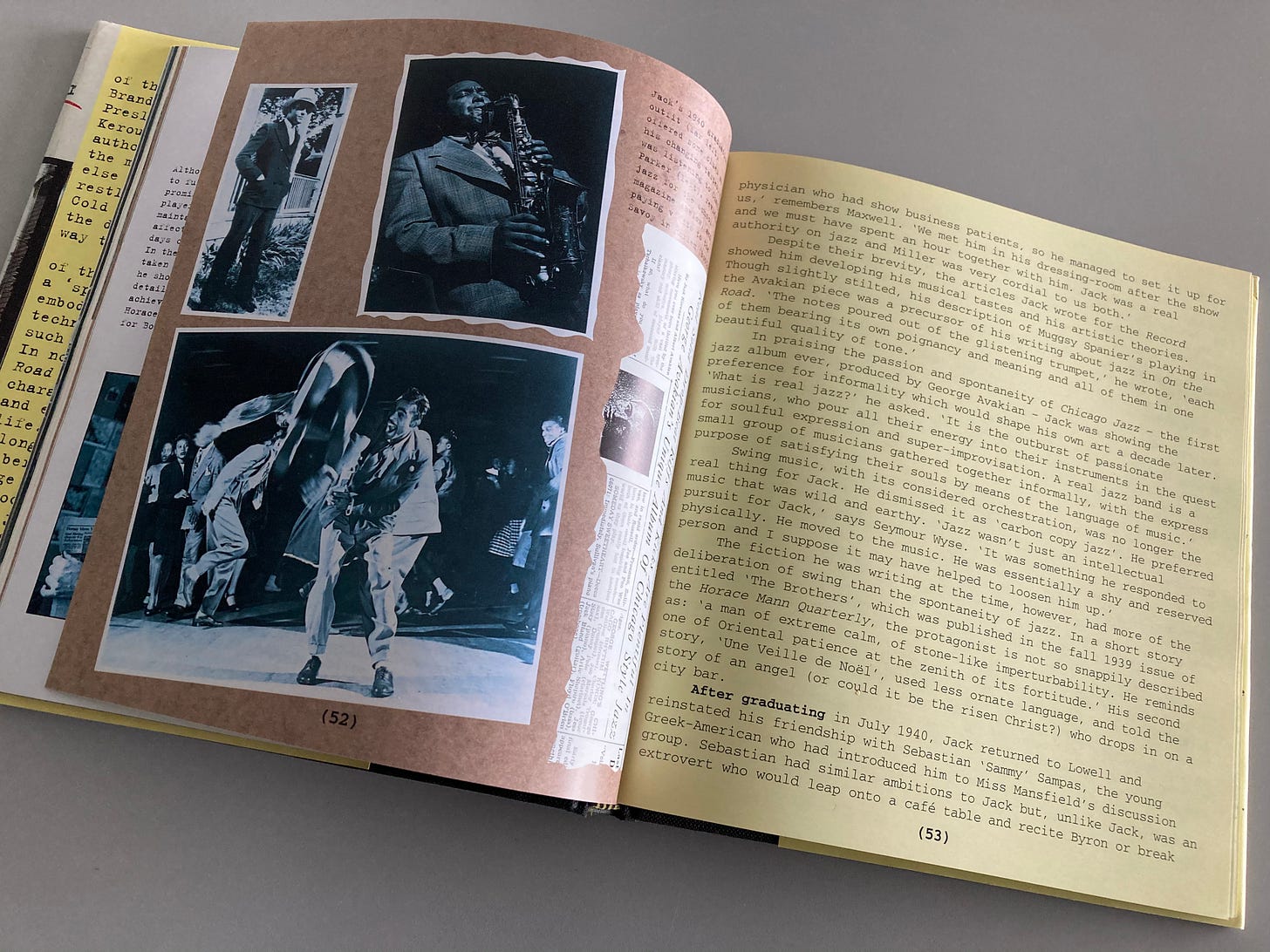

Angelheaded Hipster had a reasonably short text because the photos – which I also researched – was a vital element, as was the design. I wanted it to be a book that introduced Kerouac to people, many of whom may have been affected by Kerouac but through secondary sources.

Pictured above: Images balance the text throughout Turner’s title

I also paid particular attention to his spiritual interests which I thought had been overlooked in previous biographies. I tried to go to as many original sources as I could and fortunately a lot of his childhood friends, girlfriends, school contemporaries and Beat Generation colleagues were still around to speak to.

Were you invited by the publisher or did you pitch?

Bloomsbury had done some illustrated books about pop cultural icons and at the suggestion of Richard Williams, who had done Miles Davis and Bob Dylan for them, I was approached to do Van Morrison. Having done that I suggested to my editor, David Reynolds, that Jack Kerouac would fit into this series. He immediately went for it and I don’t think I was even asked to do a synopsis.

Bloomsbury then got Viking Penguin in New York involved to do the US edition. They then wanted me to do Burroughs, but I didn’t think I had sufficient empathy to tackle him. That was offered to Graham Caveney, who did a good job, using the same designer who worked on the Kerouac book.

Is having contact with your subject an important factor? Is that useful, vital? Or can it be unhelpful? Obviously in Kerouac’s case he was long dead.

If you do an authorised book and the subject is still living they will want a percentage of the royalties and maybe even approval of the text. If someone is no longer living they may have an estate that will similarly want financial involvement. Living subjects can contact their friends and warn them not to talk to you. Publishers today prioritise subjects who’ll tell their own stories (even if through a ghost writer) and then commit to devoting a specific amount of time publicising the book.

Pictured above: The biography is a cultural history as well as a life of Kerouac

What problems did you face in writing this particular life story?

I can’t remember problems with the writing but there were copyright issues over some of the photos. The Kerouac Estate, for example, claimed copyright on a few lines that Jack wrote in Carolyn Cassady’s copy of The Town and the City. Carolyn owned the physical object, the book, but the estate owned Kerouac’s writing.

There was another photo that Robert Frank kicked up a fuss about. John Sampas, who then ran the Kerouac Estate, showed me a small suitcase full of photos when I was in Lowell which he said I could choose from, but he eventually backed out of this altogether.

In general I’ve had more problems with American interviewees who either want to be paid to talk or think that they know so much of the story they could co-author the book with you. They sometimes even know who they want to portray them should a movie be made! Brits never talk about being paid and don’t want to take over the project.

If you're portraying or critiquing a living individual does that give you a particular obligation to the ‘truth’?

Commitment to truth should be the same, dead or alive. However, if someone is still around they can sue for slander or libel whereas the estate of a dead person can’t so you may know something to be a fact but you can’t publish if it hasn’t been proved beyond doubt.

The challenge with biography is that you’re writing something that could be read in 13 hours but covers 70 years of living. Everything is necessarily compacted. You are in the position of selecting what incidents are most interesting and illustrative of the life that has been led. It’s quite a responsibility.

You are in effect writing a report not on a person’s academic achievements in one subject, as a teacher may have to do, but on their whole life – sexual, financial, spiritual, moral, artistic and more.

When I sent a copy of The Gospel According to the Beatles to Jurgen Vollmer (a friend of the group from the Hamburg days), he read not only the chapter he was quoted in but also the whole book and he wrote a letter to me in German which my daughter translated for me. What he said was ‘That’s exactly how it was.’ That’s what I aim for. If someone involved in the story can say that of what you’ve written, I think you’ve succeeded.

Your subject had an interest in music of various kinds. How do you perceive that association – important or peripheral?

Music was very important to Jack Kerouac. He not only listened to it and wrote about it but he identified with musicians and famously wanted to write like a musician played. I think it was Ann Charters, his first biographer, who said he wrote for the ear rather than the eye. He wrote to be heard, and that’s how music affected him.

Any other thoughts?

I loved biographies even as a child when I would use my Mum’s library ticket to get adult books. I particularly liked biographies of boxers, detectives, spies and police officers. I loved the Hunter Davis biography of the Beatles published in 1968 and much later found Albert Goldman’s biography of Elvis inspirational because of the amount of research. Also, Divided Soul by David Ritz (about Marvin Gaye) was a great study of a conflicted artist torn between being a great sinner and a great saint. In fact, reading biographies has been my only education in writing them.

See also: ‘Beat Soundtrack #18: Steve Turner’, May 19th, 2022

I found this book in the tiniest and unlikeliest of bookshops in Blackburn just after it came out. I had to rush to a cash machine sharpish. A great read and a treat of photos - many I hadn't seen before at the time. I still have it.

Thanks for posting