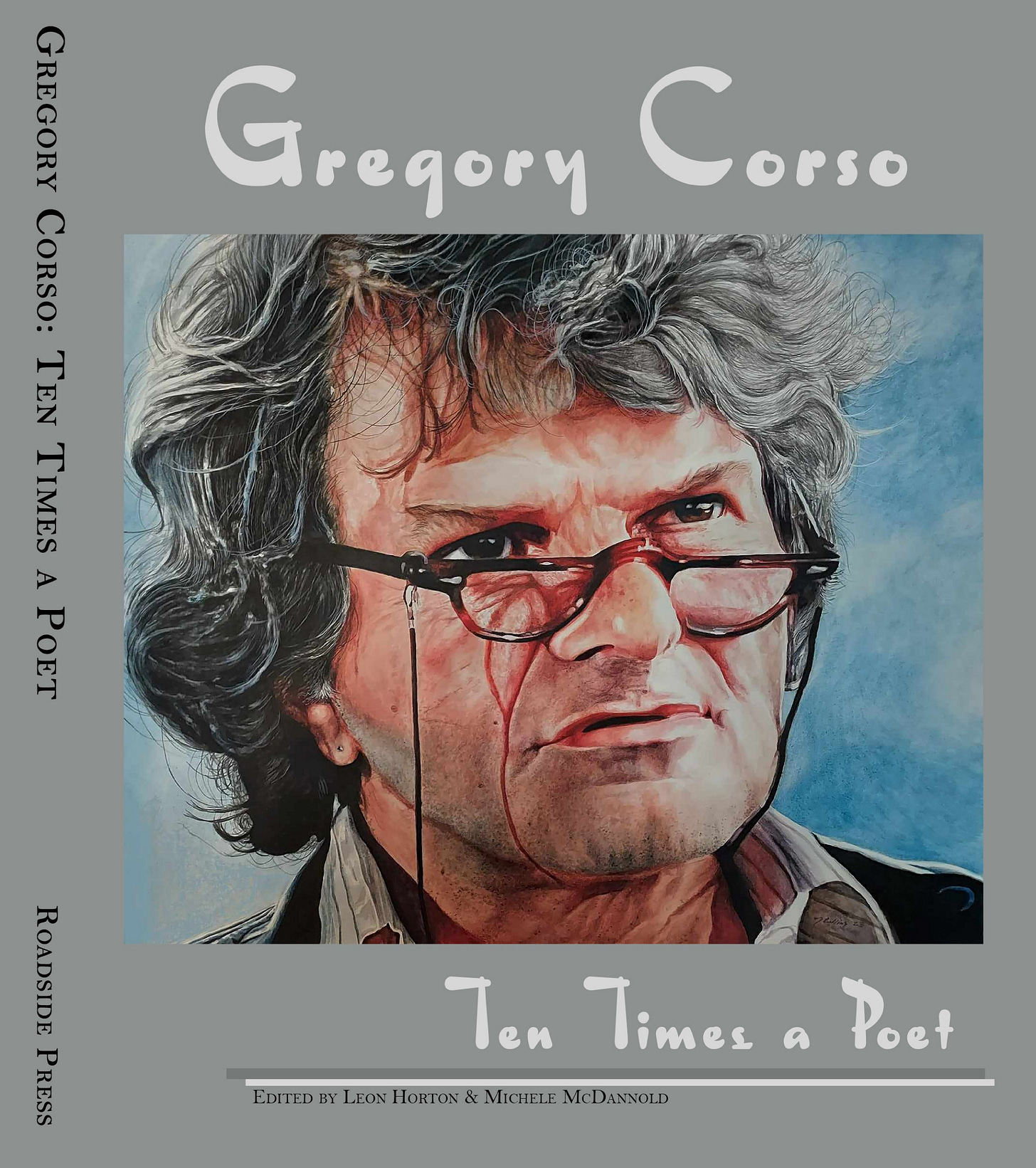

Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet, ed. by Leon Horton with Michele McDannold (Roadside Press, Colchester, IL, 2024)

By Steven Taylor

If you believe you’re a poet, then you’re saved (Corso qtd. in Horton, x)

Say you show your shit to some guy and he says this shit is shit. You say, fuck you, this is good shit (advice to a young poet, overheard at Naropa)

OF THE BEAT quartet – Corso’s ‘the four daddies’ – the least studied is the one who the others thought most gifted. Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs have each had several biographies and inspired an industry of scholarly estimations. Corso has yet to have a book-length biography, though there is a promising biography-in-process excerpted here among a welcome collection of essays and reminiscences. Corso scholarship seems to be an open field, and there is a sense of openness and generosity in the book.

In his introduction, Leon Horton writes, ‘How do you find a man in search of himself? You ask the people who knew him.’ The content of Ten Times a Poet ranges from friends’ recollections of love and misadventure to scholarly reflections, an article on his painting, and a smattering of poems, plus a couple of interviews, one with the man himself. Most of the contributors knew Corso in one way or another. Horton calls it an ‘outpouring of love for Gregory’.

Struggling to find the right tone for this piece of writing, away from the urge to relate the outrageous anecdotes of two decades’ acquaintance, I turned to the Preface of Michael Skau’s A Clown in a Grave: Complexities and Tensions in the Works of Gregory Corso (Southern Illinois UP, 1999) and read, ‘This book has been a project of love.’

This unusual opening in an academic monograph is followed by an account of Gregory heckling Chӧgyam Trungpa at Naropa in 1975. Thus, the professor emeritus begins with the bacchic motif that pulses also through the present collection: We love him; he’s trouble.

It’s impossible to speak of Corso without addressing the trope of the ‘urchin Shelley’. In his Clown in a Grave, Skau notes, ‘For Corso, the Romantic celebration of the innocence and naturalness of childhood is particularly evident, even in the poems that bemoan a hazardous upbringing . . . a nostalgia that seems to depend on the child’s very helplessness.’ There is no return from experience to innocence, but insisting on poetry’s power to make it can fetch a living.

It’s tempting to feature the misadventures and that mode is present here. Against this current, George Scrivani stresses the importance of the poetry over the anecdotal antics. ‘The myths and stories about Gregory get in the way of appreciating the work.’ Raymond Foye adds, ‘The myth was part of the man . . . When you met Gregory it was like meeting Keats or Byron, he was a poetical force of nature. Having acknowledged that, I would say in the end the only thing one should trust is the work.’ The epic really can be distracting.

On: The new Corso essay collection

But Ginsberg encouraged ‘literary gossip’; it was a favorite pastime. And as Gregory said, ‘given a choice between two things, take both’. The importance of the work is a through-line in the book, and the impact of hearing him read is vividly described, but the personal recollection is also valuable. Would that we had such intimacies of Shelley.

Allen Ginsberg introduced Corso’s Gasoline in 1958 as ‘a refinement of beauty out of a destructive atmosphere’. Several contributors here touch on the abandoned infant, foster child, runaway sleeping on rooftops, juvenile detainee, escapee and captive, and the theft of food and clothing that got him three years for grand larceny at 17. At Dannemora he read the prison library. ‘Prison made me a poet’ was one of his stock lines. When he got out, he met Ginsberg and everything but the man himself changed.

From the start, clothes were a thing. His first bust, at 13, was for stealing a suit. The charges that marked his transition from reform schools to adult jail also involved stealing clothes. Later, he borrowed. Contributor Kyle Roderick lent him a shirt to cover his needle tracks, sunglasses to hide his pinned pupils, and a pair of her father’s boxer shorts to keep him decent.

On tour in 1979, he advised me to ‘always wear at least one classy piece’, as I handed over the dress shirt I had stashed in my grip for a special occasion. He wore it for weeks, on a string of one-nighters from Amsterdam to Rome, its ample tails covering the split-ass red velvet pants he had borrowed from a girlfriend.

Gregory in a word: needy. In two words: endlessly needy. When you’re on tour with a company of actors and poets in a van all day on winding roads in the chill fog of Torino in winter, the perpetual comedy of suffering genius is exhausting; then at day’s end, when you get to the gig and he reads ‘I Held a Shelley Manuscript’, nothing else in the world matters. His gift carried him for seven decades through all manner of difficulties, and that he lived as long as he did is testament to the power of his poetry and the love it drew forth.

Horton notes that publishers found him difficult to work with. This sort of thing often has to do with deadlines. Ginsberg was terrible at deadlines. If you walked into Allen’s apartment and found him vacuum-cleaning the whole pad, for sure he was avoiding a deadline. But with Corso, it was more complicated. He broke into City Lights and stole cash.

Some missteps had comedic complications. Allen calls me from Colorado. He says someone had given Gregory a kitten while he was finishing a manuscript for his publisher. He would type a page and drop it in a cardboard box on his closet floor. When the manuscript was complete, he sealed the box and had it shipped to New Directions. Allen laughs, ‘Imagine the secretaries having to steam the pages apart!’

Twenty years later, typing what would be his final manuscript, he neglects to change the ribbon when it stops printing, and, after he’s gone, editor Raymond Foye has to run a soft pencil over the pages to reveal the indentations of the type.

The main through-line in this outpouring is that, first and last, he was a poet. At a time when no one made a living as a poet, Gregory undertook to pull it off. Supporting his quest was a communal exercise. Many gave cash willingly in amounts large and small, some lost pawnable items, some petty cash. Whenever he stayed at Ginsberg’s place in the East Village, the guest room that doubled as a storage space was emptied of valuables before he arrived.

When he was at ease, in a safe place such as Allen’s apartment, with a warm bed waiting and a well-stocked kitchen, someone to fetch a bottle, and a telephone to run up to staggering levels of expense by hours-long chats with his lover wherever she may be, he was good company.

My fondest memories of Gregory are of listening to music. One interviewee says that Gregory grew to hate music. That doesn’t seem right. Perhaps as he grew older he grew less patient with imperfection. I could see that. In the leaky lifeboat, there is only so much time. But I remember listening to Bach’s St Matthew Passion with him and a bottle of Burgundy; it was wonderful, because he felt the music so deeply. I told him about my choral setting of ‘Footnote to Howl’, then in progress. He said, ‘Write the atom bomb “Te Deum”.’

In dedicating his Selected Poems to Corso in 1995, Ginsberg calls him ‘Father poet of Concision’. Every syllable had to be fully charged. He was forever refining. Like Allen, and like jazz musicians who perfect a piece over a series of performances, he used his live readings to refine his delivery. But Allen thrived on performance, while Gregory did not take to it naturally.

During a reading at Naropa circa ‘88, he interrupted his program to confess his perpetual discomfort at being urged to read for all these years by ‘Ginzy’. His was a private struggle, though only in the art. He worked constantly but published sparsely. After Gasoline, in1958, he published three books between 1960 and 1981. And the next book, in 1989, was New and Collected. This is not to say he wrote sporadically. He was always on. In 1990 he stopped publishing and he died in 2001, leaving a typescript with a friend. The final book The Golden Dot, edited by George Scrivani and Raymond Foye on Lithic Press, came out in 2022.

Poetry was his sole practice. If you are going to master the horn, you must do nothing but blow. There is, in the present volume, a two-page spread reprinted from a magazine, ‘Between Childhood and Manhood’, in which Gregory, then 35, ruminates on time and the course of life. It’s a little clumsy here and there, but has some lovely moments. It reminded me of his ‘Marriage’ poem, but is much less refined.

It reminded me also of his claim that he was not schooled past sixth grade. Whitman left school in Brooklyn at about the same age, though he mastered a couple of trades beside poetry. Gregory’s sole trade was verse. As Raymond Foye points out in his essay, he was always working a poem. ‘There was never a time when he wasn’t with the poem. . . . His poetry was an argument with himself. I never knew anyone who worked harder than he did.’

There are a lot of great pieces here, but Kay McDonough’s strikes me most. ‘I was mad for Gregory, and I didn't die from it. . . He was better than Byron or Shelley . . . because he was alive.’ That was the thing, the insistent presence of the herald.

Way back, at midnight on an endless road in Veneto, he points to the waxing moon above the trees. ‘Looks like a sail.’ Forty-five years along, I still wonder why the moment was so striking. Maybe it’s because when the maestro blows a choriamb, all time is in it.

Editor’s note: Steven Taylor is a writer and musician. He was Allen Ginsberg’s guitar accompanist for 20 years.

See also: ‘Beat Meetings #1: Steven Taylor & Gregory Corso’, February 24th, 2023