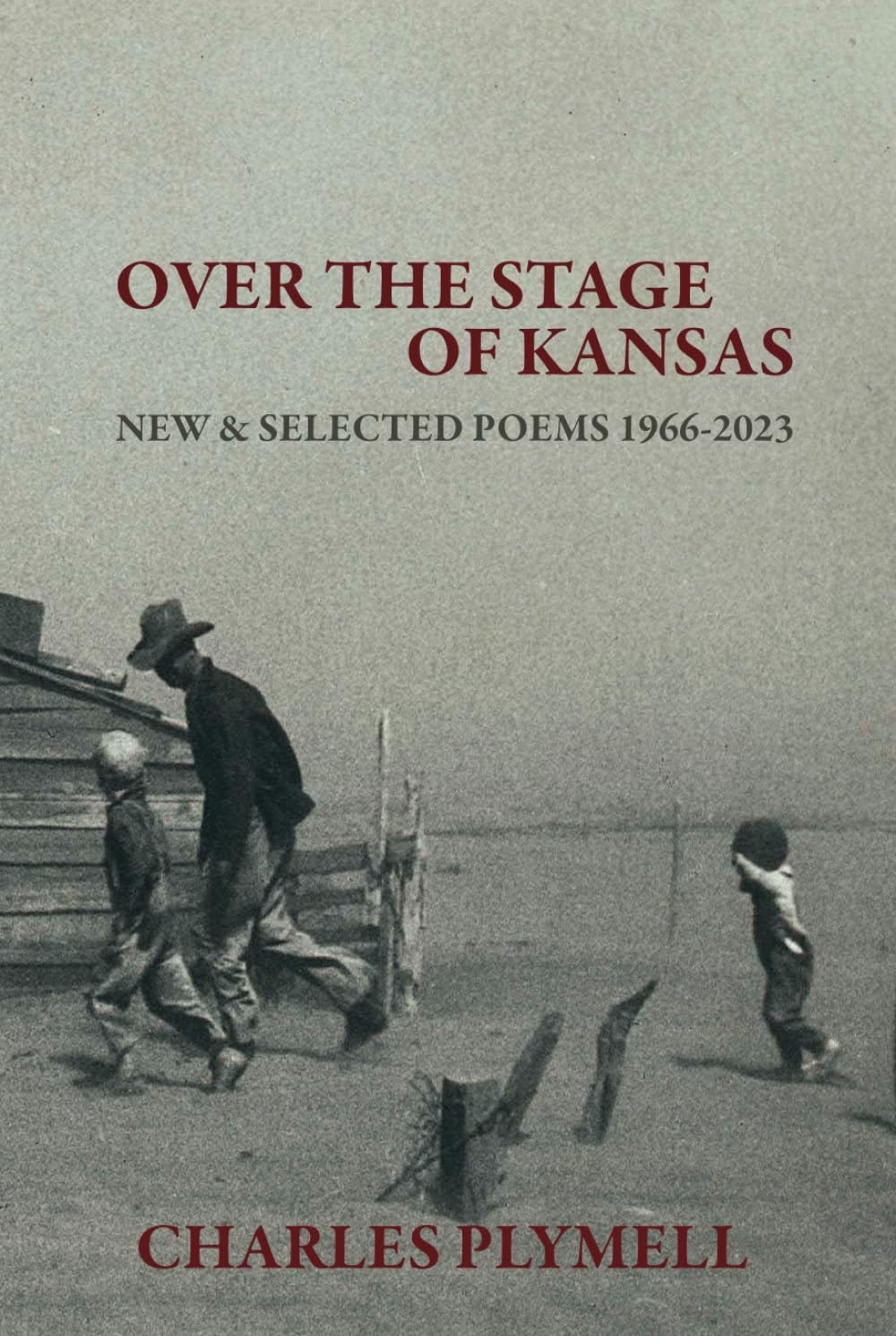

Over the Stage of Kansas: New and Selected Poems, 1966-2023 by Charles Plymell, ed. by Gerard Malanga (Bottle of Smoke Press, 2024)

By Jonah Raskin

UNTIL VERY recently I did not know the name Charles Plymell and, when I first saw it in an email, I didn’t recognize it or realize that Plymell is a poet and has been one for the past six decades and perhaps longer than that. The poem, ‘Memories of Gila Bend, Ariz’, which is included in Over the Stage of Kansas, is dated circa 1950. If it was indeed written at the very start of the 1950s, that would mean that Plymell began his long vocation as a poet prior to the inception of the Beat Generation.

Before Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin opened City Lights Bookstore, before Ferlinghetti published Howl and Other Poems, before Kerouac embraced Buddhism and predicted the coming of the ‘rucksack revolution’, and before Neal Cassady received $20,000 from the South Pacific Railroad following his injury in a train accident.

Charles Plymell, who was born in Kansas in 1935, during the time of the dust storms, was a Beat poet before John Clellon Holmes used the phrase ‘the Beat Generation’ in his groundbreaking article for the New York Times, ‘This is the Beat Generation’ in 1952. Plymell was also a real rock ‘n’ roller before Elvis Presley walked into Sun Records and began his decades long reign as the ‘King of Rock and Roll’.

Beat history goes back a long way. It also goes beyond New York and San Francisco. Perhaps it began in the American west, a territory that Plymell explores in many of his poems, though he explores many other places including New Jersey, Hollywood, London and Paris, where he seems to be at home. Perhaps Plymell wasn’t boasting when he said that he did what Ginsberg and Kerouac did before they did it. Maybe he was just stating the facts.

In ‘Memories of Gila Bend, Ariz’, he writes, ‘we bunked in railroad cars/ with a saddle for a pillow’ and ‘we threw empty whiskey bottles/ on the highway, shot up road signs/ near the border, fucked senoritas’. Yes, that’s what the hipsters and the pre-Beats did on the road and off the road.

Pictured above: Charles ‘Charley’ Plymell

‘Memories of Gila Bend, Ariz’ moves from ‘we’ in the first three stanzas to ‘I’ in the last five stanzas. ‘I’ being the most favored pronoun for the Beats, as in Ginsberg’s ‘I saw the best minds of my generation’, Kerouac’s ‘I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up’, and Burroughs’ ‘I can feel the heat closing in, feel them out there making their moves, setting up their devil doll stool pigeons.’

Plymell was following Kerouac’s suggestions for writing spontaneous prose before Kerouac made his famous list. ‘Memories of Gila Bend’ ends with a quotation from a cowboy who tells the poet that on a bucking bronco he was ‘bucked so high,/ he could have built a birdnest in my ass’. Plymell listens to America and Americans. He hears America talking and singing folk songs, the blues and country and western ballads.

I could have known about Plymell long ago, should have known about him, and would have known about him if I had paid more attention to twentieth-century American poetry and if I had read Allen Ginsberg’s Collected Poems more carefully than I did when I read it. I looked at the index the other day and found two entries for Plymell. Ginsberg knew about him long ago.

Also, on the back cover of Over the Stage of Kansas, I read a blurb from Ginsberg and another from Burroughs. ‘Plymell and his friends inventing the Wichita Vortex contribute to a tradition stretching back to Poe,’ Ginsberg wrote. Ginsberg made Kansas famous in his 1960s poem ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’. In his blurb Burroughs wrote, ‘Plymell has as much in depth to say about death as Hemingway.’ He might have added that he has as much to say about life as Walt Whitman.

Does the work of Plymell belong in the same premier league as Hemingway and Poe one might ask? Poet and critic plus Warhol sideman Gerard Malanga, who edited this volume, writes in his ‘Foreword’, titled ‘Charles Plymell aka Charley’, that his ‘work represents some of the best poetry written in America at this or at any other time.’ He adds, ‘It just is. Real & honest.’ That’s all he says. Alas, no analysis or interpretation.

I try not to use words like ‘best’ and ‘better’. Who is to say what is the best or better. Perhaps an editor at the Times Literary Supplement, but certainly not me. I can say that I like Plymell’s poetry as well as I like anyone else’s poetry right now. Some of the appeal is because of the novelty of his work. Also, Plymell clearly belongs to the extended tribe of the Beats. He adds his own unique voice and vision to the extensive body of poetry that already exists.

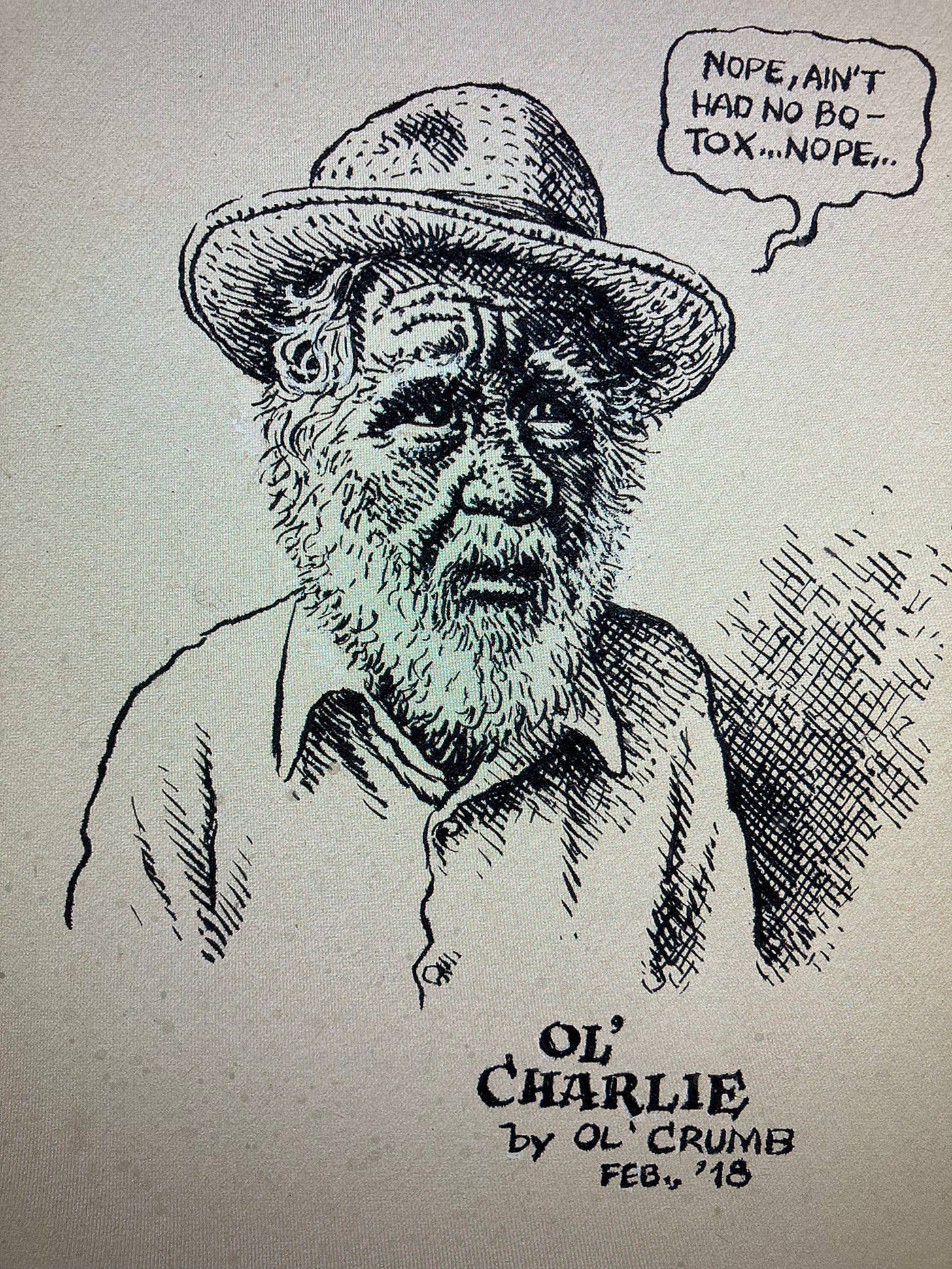

Pictured above: Plymell captured by Robert Crumb

Over the Stage of Kansas offers nearly 200 poems, culled from 12 different collections of poetry with titles such as Neon Poems, Trashing of America, Hand on the Doorknob and Eat Not Thy Mind. There’s a lot of work to choose from and a lot to like.

Poems with rhymes and without rhymes, long poems and short poems, poems that spring from memory and poems that rise from observation and reflection. One might note that the third word in the title is ‘stage’ not ‘state’. The poet’s Kansas is a place where actors enter and exit, speak their lines and depart.

If I had to label Plymell I'd say he’s Beat, pre-Beat and post-Beat. In the poem titled ‘Ragtime’, dated 1965, and with the added words ‘The Tenderloin, San Francisco’, which pulled me in instantly and held my attention, Plymell writes about ‘meth’, ‘the teen-age revolt’ and about ‘all night Beatles post-Beat rock and roll’. In the last stanza he returns from the street to his room and thinks of a ‘great line’ for a poem, but can't find a pen or pencil to write it down.

The self-mocking appeals to me and might also appeal to readers bored with narcissistic poets who take themselves far too seriously (Plymell might not be more famous than he is because he doesn’t take himself all that seriously. He’s not a full time promoter, though he is a legendary and an iconic figure in photos that show him with a white beard, wearing a hat and holding a pen in his right hand.) Plymell is also as much at home in museums and art galleries, the world of Giotto, Modigliani and Rembrandt, as he is in ‘meth streets’.

The poem titled ‘Apocalypse Rose’ particularly grabbed my attention. I’m partial to apocalyptic poems. Plymell’s phrase reminded me of Ginsberg’s ‘hydrogen jukebox’. In ‘Apocalypse Rose’, Plymell writes about ‘the boy’ who ‘dreams of gangsters, jazz, Chuck Berry, Bill Haley, And Elvis singing’. The boy might be Charles Plymell or he might be almost any boy in Wichita, Liverpool, London, San Francisco or Chicago. Plymell honors nearly all the rock ‘n’ rollers he ought to honor, and honors Burroughs, Ginsberg, Kerouac, Corso, Herbert Huncke, Anne Waldman, Neal Cassady and his son John, Ray Bremser, and Joanna McClure.

The book is dedicated to ‘Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Ferlinghetti’. The ‘Lieutenant Commander’ part sounds cheeky. Plymell can be wistful and angry as in ‘Politics Be Damned’ in which he writes, ‘So take Your fucking America Bruce Springsteen’. He also writes about ‘political leaders’ caught playing the game ‘the convict already knows’. Could that be Nixon or Trump? Plymell loathes America’s political leaders and loves its hobos and bums. He loves the Sioux, the Cherokee and the Paiute who inhabited the Great Plains and who punctuate his poems.

I like most of Plymell’s work that’s set in and about Kansas, including ‘In Kansas’ in which he writes ‘in Kansas you may have/ the madman’s dream, white whale on the desolate plains./ Or wild strawberries/ of a baby’s dream/crushed beyond repair’. I also take delight in the ten-line poem titled ‘I Used to Shit out on the Prairie’, which incorporates the title in the body of the poem itself and repeats it three times, each time with more emphasis.

Plymell is nearly always connected to the prairie, the Great Plains, and to his own body and his bodily functions, which is to say that he’s ground even when he soars like an eagle of the state and the stage. I will never forget his poems included in the New and Selected Poems, 1966-2023, which belongs on the shelf next to Ginsberg’s Collected Poems and Ezra Pound’s The Cantos. Charles Plymell belongs to Kansas and to the cosmos, to today, yesterday and tomorrow.

I had the good fortune of running into Charles Plymell years ago in Cherry Valley,New York, before I knew who he was . With my good friend (a jazz pianist) who lived up in Ft Plain NY we took a ramble down to Cherry Valley looking for Paul Bley ,the jazz great. Someone ,who turned out to be Charlie Plymell, heard us talking in a cafe ,or bookstore -and introduced himself. We never connected with Paul Bley -but we spent an unforgettable eye opening afternoon with Charlie Plymell who took us back to his house and told us stories about Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, et.al & Kansas . . We had really stumbled onto a relatively unknown Giant of real deal Bohemia & Beatdom whose humane-ness and decency were so profoundly apparent in the courtesy and interest he extended to complete strangers. Beat generosity and hospitality on full display-with no ulterior motive . Shortly after that back in the City , at the Strand I discovered Benzedrine Highway"Hi-Octane Early Work" with the forward by Ginsberg ,which contains "Apocalypse Rose" that Jonah Raskin so powerfully champions. More significant ,I think than the blurbs by Burroughs,and Ferlinghetti , who are, after all, confreres, is Tom Wolfe's blurb that likens Benzedrine Highway to Tropic of Cancer, Naked Lunch & Castle to Castle . So glad that he's now getting the accolades he deserves from no less than J.Raskin -

Fabulous anecdote, Dave. What a great encounter!