Book review #31: The Burroughs-Warhol Connection

Cultural giants and their famous circles explored

The Burroughs-Warhol Connection by Victor Bockris (Beatdom Books, 2024)

By Jonah Raskin

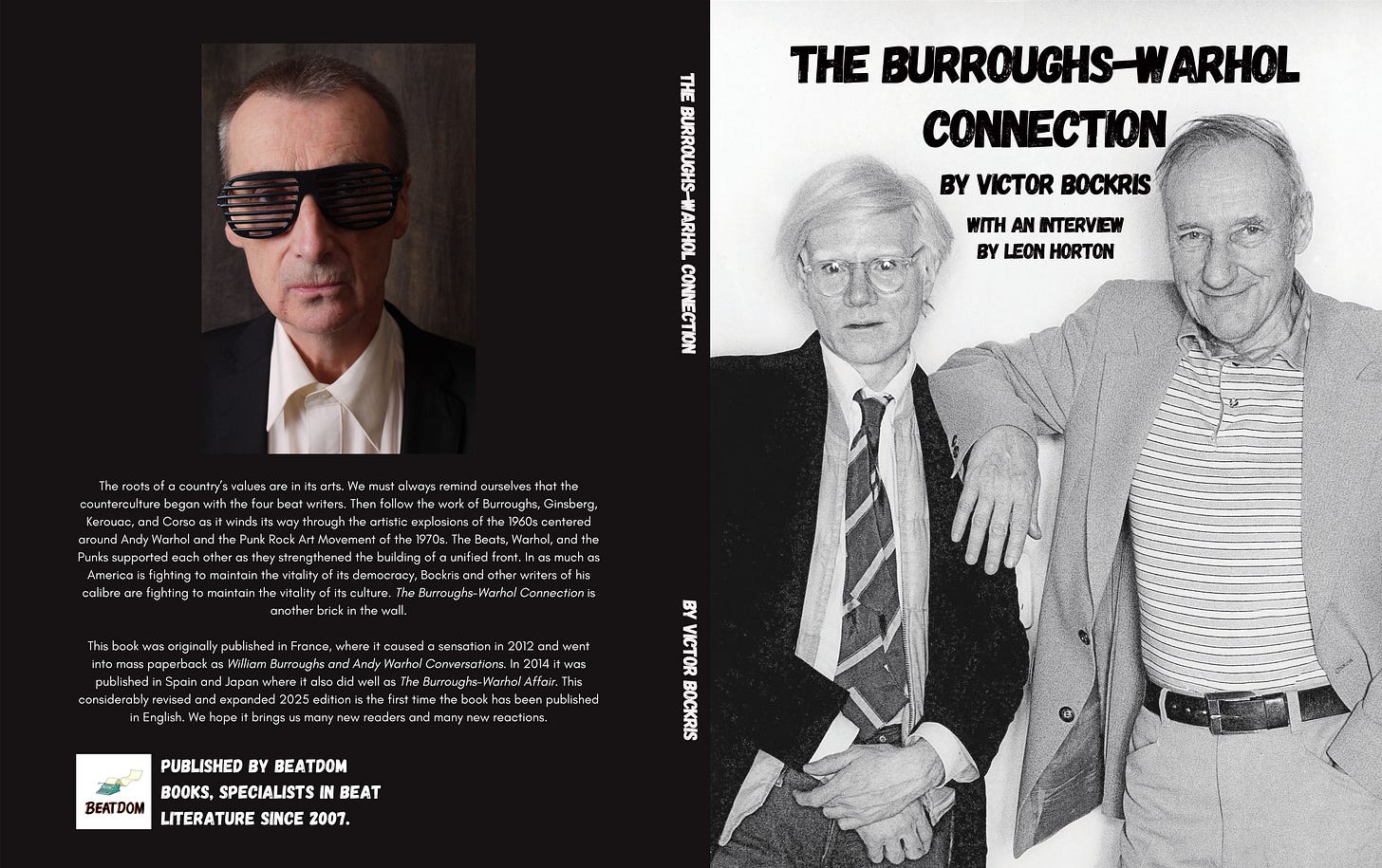

VICTOR BOCKRIS’s The Burroughs-Warhol Connection – which has just appeared in print in English in a lavish new edition – has enjoyed several earlier, somewhat different global, incarnations. First published in France in 2012 under the title William Burroughs and Andy Warhol Conversations, it was reissued in Spain and in Japan in 2014 as The Burroughs-Warhol Affair.

For me, ‘connection’, as in the Stones’ hit ‘Connection’, sounds hipper than 'conversation’, which makes me think of the TV hipster square Dick Cavett. ‘Affair’, as in Grahame Greene’s novel The End of the Affair, sounds sexier than ‘connection’ and ‘conversation’ yoked together.

Why, one might ask, has it taken more than a decade for the book to be published in English and with a new title? Perhaps because no English or American publisher had the guts of Beatdom, which has specialized in Beat literature since 2007. Call The Burroughs-Warhol Connection a breakthrough book for that indie publishing house, one that deftly contextualizes the two wizards of the word and the image.

Part collage, part montage and part a cultural history of rock‘n’roll, experimental film and avant-garde art, this 204-page volume brings together a large cast of unforgettable characters, from Mick Jagger and Patti Smith to Allen Ginsberg and Lou Reed, all clustered around those two multi-media mega stars of the twentieth-century: William Burroughs, the master of the cut-up, and Andy Warhol, the master of Pop Art.

Untidy and made-up of bits and pieces in both words and photos, The Burroughs-Warhol Connection follows no clear chronology or obvious themes but does pursue the orbits of the stars whose careers the author follows with meticulous detail.

Bockris, who was born in Britain and raised in England and the USA, has, for decades, rubbed shoulders with the famous and the infamous. He has also devoted his life to the recording and documenting of the lives and the works of celebrities, while he has remained largely in the background and less well known, for example, than his friend Barry Miles, who has written brilliant books about Ginsberg, hippies and Burroughs, who was often known as L’Homme Invisible. After reading Bockris’ book one might think of him as L’Homme Visible.

Perhaps The Burroughs-Warhol Connection will provide Bockris with the recognition that he has long-deserved and has not yet received. One hopes so. The interview with him by Leon Horton, included here, ought to help. Publishers are often notoriously enigmatic and secretive; they make decisions behind closed doors.

Maybe Bockris is too honest about himself to be heralded and publicized by, say, Random House, Simon and Schuster, Faber or Oxford University Press. In the pages of his Burroughs & Warhol book, he, for instance, condemns his own biography of Patti Smith, the publication of which led to an acrimonious split between the author and the poet-singer.

In the candid interview with UK writer Horton, which appears at the back of this book, Bockris says, 'I did not take care of myself. I worked too long, without a proper break and I abandoned my calling without even knowing it.' He adds: ‘I had been using mucho drugs and alcohol…I became a mess, a horrible stinking mess!’

We expect rock and movie stars to abuse drugs and alcohol and to go to extremes, but we’re usually intolerant of reporters and journalist who abandon their calling and go mucho and gonzo. Hunter S. Thompson was a rare and wonderful exception; he lived the life he wrote about in his ‘Fear and Loathing’ books, and, possibly not surprisingly, committed suicide aged 67. At 75, Bockris has lived a relatively long life. Warhol died at 58, though he survived the attack by Valerie Solinas in 1968. Burroughs amazed us, enduring to a ripe old 83.

By living up close and intimate time after time with Burroughs, Warhol, Jagger, Ginsberg and others, Bockris was on the scene to hear and record quotable quotations that no reporter on a short leash, a tight-deadline and with a limited word-length would likely hear and record. This committed observer put in the time and it paid off.

Ginsberg talks about Warhol’s ‘strangeness’, ‘mysteriousness’ and ‘mindfulness’. Burroughs says, ‘there’s no such thing as the unconscious any longer’. On the subject of Mick Jagger, the Naked Lunch author comments, ‘There’s something about him that arouses great antagonism…to be able to stand up to that and to be cool is quite something.’

Burroughs is also absolutely brilliant in a way that only he could be when he describes a rock concert as ‘a rite involving the evocation and transmutation of energy’. That’s the way I myself experienced rock concerts especially when I saw and heard artists of the calibre of Tina Turner and the Stones, Chrissie Hynde and the Pretenders and Iggy Pop.

For all his acumen as a photojournalist and interviewer, Bockris is way more than just a machine taking pictures and recording voices and sounds. He’s a thinker of the first order especially when he goes into extended riffs on the similarities and the differences between Burroughs and Warhol.

Both of his subjects here, Bockris points out, depended on drugs: Warhol on amphetamines, Burroughs on heroin. Both were well informed about surrealist film, both made the tape recorder pivotal to their work and both worked from inside their headquarters: Burroughs in his Bunker and Warhol in his Factory. Their entourages, Bockris explains, were also their collectives.

They were both romantics and both were ‘double agents,’ Bockris insists: men who were married to their work and of necessity had to be alone. ‘Andy fell in love with thousands of people for five minutes,’ Bockris says, surely meaning to recycle the observation often attributed to Warhol himself that ‘In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.’ On the subject of Ginsberg, Bockris says that it was ‘hard not to love’ him, but that he had 'a hard time loving himself’. That sounds like an accurate assessment.

Bockris’s intimacy with Ginsberg, Burroughs, Warhol and Patti Smith yielded insider information and knowledge, but that closeness also may have warped his judgments, especially when he concludes, for example, that Warhol’s a: A Novel is ‘one of the key texts of the sixties.’ The title is cute and memorable, but the work itself is mostly forgettable. Still, the New York Times called it a ‘work of genius’.

Bockris has been totally serious for decades about his ‘calling’, as he describes it, but he also had an ear for what I take to be humor. He includes a discussion between Warhol and Burroughs about the most famous Jews in history. Burroughs suggests Kafka and Einstein, Freud and Marx – betraying his own intellectual bent and Harvard background. Warhol adds the names, Gertrude Stein and the Marx Brothers, underlining his affinity for experimental fiction and pop culture. Two non-Jews riffing on famous Jews. Now that’s funny.

In his interview with Horton, Bockris adopts much the same perspective that the English fiction writer and literary critic E. M. Forster expressed in Aspects of the Novel, in which he imagined all of the major British authors writing at the same time and in the same place: the British Museum Reading Room.

Forster also argued that throughout history, tyrants and autocrats, from the Medici to the kings of France, held sway over citizens, and made messes, but that artists from Michelangelo to Molière, turned the messes of the ages in which they lived into masterpieces.

As for now, Bockris explains, ‘We are watching the collapse of the American Empire’, though he’s not weeping. Burroughs and Warhol might be viewed as products of a decadent empire, but they are products who enjoyed decadence and who memorialized many of its bizarre twists and turns on the way down.

Bockris adds, apropos the empire, ‘censorship has come and gone, our greatest artists from the 1950s to the present remain. We still reference Oscar Wilde. Ali remains. The Stones continue rolling.’

Yes, yes, rock‘n’roll is here to stay and the Beats go on, thanks in part to Bockris’ loyalty to Ginsberg and Burroughs, as well as to Warhol and Jagger, Lou Reed and Patti Smith. About Smith, the punk poet whose first book of poetry he published, Bockris says, ‘I wish I could have written the great book I could have written.’

Victor, we forgive you. You may have lost your way in the 1990s, as you yourself suggest, but you truly inhabited the 1970s and the 1980s and put your stamp on those decades. It’s not hard to love you and your books.

See also: ‘Thirty up! R&BG’s book reviews updated’, August 31st, 2024

Jonah has once again written a masterful review.

Victor wrote masterful interviews for the Coldspring Journal: Claude Pelieu and Mary Beach;Tennessee Williams. I loved publishing them. Victor is a genius.

An excellent review! Thank you Jonah and Simon.