Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night that Split the Sixties by Elijah Wald (Dey Street, 2015)

THE MOST famous, some may argue still the most significant, biography of Bob Dylan is the late Robert Shelton’s 1986 effort, one that takes its title, No Direction Home, from an important refrain in Dylan’s crucial, agenda-setting 1965 song ‘Like a Rolling Stone’.

Now, an artwork in a different medium – film – has dislodged a further fragment from that composition’s powerful and compelling lyric to name a picture commemorating a vital period in the early Dylan narrative.

A Complete Unknown depicts those years between the singer’s arrival in New York City at the start of 1961 to the latter half of 1965 when the fallout from his headline-grabbing amplified performance at the Newport Folk Festival generated a range of raging emotions among his followers, those for and those against his electric conversion.

The big screen drama – not a biopic, more a fable, insists established director James Mangold – is unveiled in the US this month and debuts in the UK in January. It showcases perhaps Hollywood’s most charismatic screen star of the moment in Timothée Chalamet, the French-American actor, in the central role of the young and speedily evolving Dylan, as Midwest ingenue transforms into musical Messiah.

The movie production, in which Chalamet does his own singing, also pays due credit to its principal inspiration, Elijah Wald’s or book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night that Split the Sixties, his much-revered account of the artist’s stage blowout in folk’s most hallowed court, tradition shattered by the gritty growl of a couple of Fenders, acoustic purity quaking in the face of amplified modernity.

With the imminent arrival of the cinema release, it seemed a reasonable moment to re-visit Wald’s finely-detailed re-telling, which originally emerged exactly 50 years after Dylan’s revolutionary snarl, as clear an attempt at myth-busting as you’re likely to find regarding that Damascene, Sunday night moment in the fractious history of the American folk movement.

How had this slight figure, ‘a cross between a choir boy and a beatnik’ to quote reviewer Shelton’s famed and glowing notice for the New York Times on September 29th, 1961, become so quickly a spikily angry young man on a national festival stage? How could that frail solo voice be suddenly cast as the frontman of a renegade band, a motorcycle gang some proposed, replete in outlaw chic?

Wald’s dissection of the seminal events that lead to this explosive eruption in the long arc of twentieth-century American popular music is well-paced, readable and rich in detail. The author, in an eclectic career, has moved comfortably between the roles of musician, journalist and academic and his insights are based on much first-hand experience and a dedicated researcher’s pursuit of essential truths.

In the 1970s, he became close to the legendary Dave Van Ronk – a Greenwich Village stalwart and a major influence on Dylan – and later collaborated on the man’s autobiography The Mayor of MacDougal Street from 2005. Four years on, Wald penned an influential piece of commentary – How the Beatles Destroyed Rock’n’Roll – which helped make his reputation as a serious cultural detective, not afraid of positing a counter thesis, on the university campus circuit.

Dylan Goes Electric! is particularly good on its analysis of the reception of the incendiary Newport set. Was there booing? Was there cheering? Who was booing? Why were they booing? Was the sound system the problem? Were the stuttering delays a cause of the turmoil? Was the brevity of the actual performance at the heart of the furore?

Were those suggestions that Pete Seeger had an axe – there were feverish rumours that this great figurehead of the roots community had threatened to cut the cables to Dylan’s blaring sound system – true or were they curiously confused with a request for ‘an axe’ when the singer, caught in the eye of this aural storm, asked for someone to loan him an acoustic instrument to furnish a consolatory unplugged encore?

The writer pulls together a kaleidoscope of takes on the incident. Alan Lomax believes that Dylan had ‘more or less killed the festival’. Paul Rothchild reported that he had seen Seeger with an axe. Maria Muldaur described the performance as ‘Godawful loud’. And Erich Von Schmidt claimed that Dylan’s lead guitarist on stage Mike Bloomfield was ‘out to kill’. And there are many more views beside.

Wald summarises coolly and calmly. ‘On the tape it is hard to hear much booing during the electric show – in part because the stage microphones were turned down to deal with the volume, so very little crowd noise came through – but almost everyone in the audience remembers it. Some tried to quantify the reaction, saying half were cheering and half booing, or the proportions was sixty/forty, or eighty/twenty…’

One person who did openly admire Dylan’s unexpected, some would claim provocative, gesture was his friend Allen Ginsberg, who later praised the singer’s audacious show of creative autonomy. But Ginsberg, who had met the singer at the very end of 1963 and instantly formed a bond, is not present at all in Wald’s overview of these changin’ times.

But what other Beat evidence can we glean from this volume’s fluent, assured and interrogative pages? Is that literary strain sewn somewhere into the book’s fabric? The evidence is surprisingly quite thin but worth teasing out nonetheless.

Jack Kerouac is a presence, a spectre, if only a fleeting figure, in Wald’s helpful and extended preamble to the Newport flashpoint, framing Dylan’s days in Minnesota and his snappy Manhattan ascent. This insightful investigation makes a very early connection to that radical and literate consciousness with which the singer would become widely associated.

By the time of that notorious in-concert flashpoint, the writer explains, Dylan was ‘already recognised as a mercurial genius, the ultimate outsider, compared to Woody Guthrie in Bound for Glory, Jack Kerouac in On the Road, Marlon Brando in The Wild One, Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye, the alienated Mearsault in Albert Camus’ Stranger – and most frequently of all to James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause.’

When Dylan undertakes personal odysseys across the US – alone in the summer and fall of 1960 and with a group of friends in winter 1964 – there is a strong feeling he is living out a novelistic experiment, one prompted by On the Road or perhaps more likely, in the earlier instance, by Bound for Glory. He has assimilated a template for his own artistic evolution, one to be cultivated, maybe fabricated, in transit.

Guthrie’s somewhat fictionalised travelogue had been available since the 1940s though Kerouac’s key novel had also certainly made waves following its appearance in 1957. But had Dylan managed to read On the Road before the decade actually concluded?

In various places, it is reported that the singer had encountered work by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso and Kerouac’s poetry cycle Mexico City Blues while in Minneapolis, as he began his debut university semester during later 1959. But the most famous Beat novel of all does not seem to be obviously cited in his reading list of that time, as the young Dylan acquainted himself with the outsider circles who gathered in Dinkytown, the city’s bohemian neighbourhood.

Five years on, when he embarks on a further road trip with a trio of newer associates, Wald talks about an adventure with a boys’ club, four young men together, at its heart. ‘They drove,’ he states, ‘across the country, holding their car to the white line in Kerouac’s holy road, from New York to New Orleans, then west to San Francisco’. It was a trek, the writer characterises as ‘fraught with legend and nostalgia’.

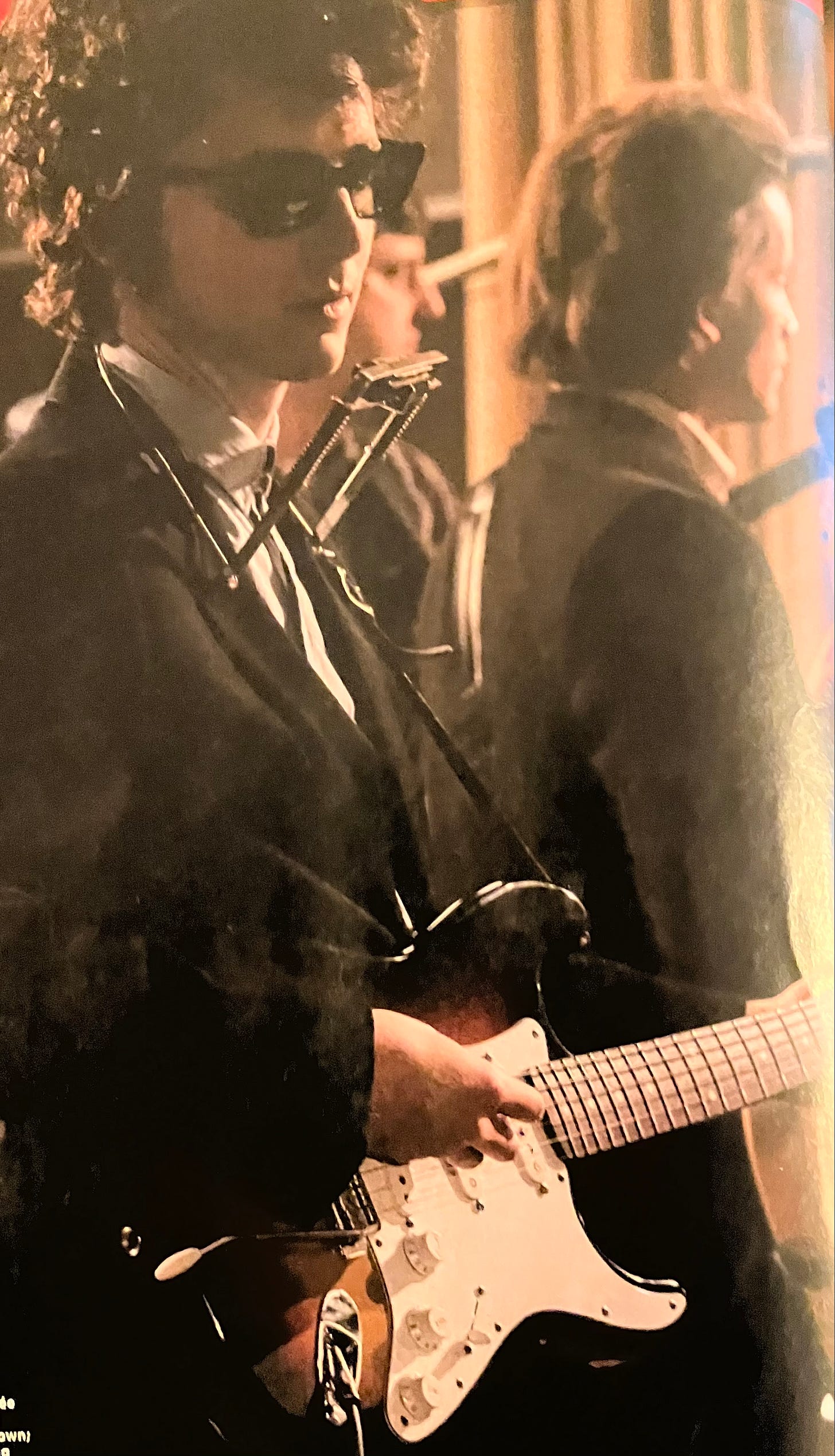

Pictured above: Timothée Chalamet as Dylan in A Complete Unknown

But to return to the cinematic version that will aim to capture an authentic flavour of the developments which shaped the first half of Dylan’s momentous 60s, one of the rather gripping revelations regarding A Complete Unknown is the singer’s own participation in the new celluloid project.

James Mangold, who steered the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line to Academy Award glory in 2005, was particularly pleased that Dylan, taking a break from his Covid disrupted live tour, proved happy to discuss the script and plot details with the filmmaker face-to-face.

He told a recent edition of Mojo: ‘We sat down and had a series of one-to-one meetings, four or five time for at least a half day, just the two of us drinking coffee. And it became a huge opportunity for me to fill in the cracks in the story […] I felt incredibly honoured to get a sense of his own perceptions of that moment so far away…’

Remarkably, Dylan also weighs in as the promotional truck gains speed, announcing: ‘There’s a movie about me opening soon called A Complete Unknown (what a title!). Timothée Chalamet is starring in the leading role. Timmy’s a brilliant actor so I’m sure he’s going to be completely believable as me. Or a younger me. Or some other me. The film’s taken from Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric! – a book that came out in 2015. It’s a fantastic re-telling of events from the early 60s that led up to the fiasco at Newport. After you’ve seen the movie read the book.’ Now, there is a recommend!

For the new movie, if director Mangold is to be believed, perhaps its semi-mythical style will be closer to Scorsese’s 2019 Rolling Thunder Revue, which played some surprising games with the truth, than Marty’s hard-faced documentary reality of 2005’s No Direction Home, but certainly more grounded in actuality than the surreal multi-actor shenanigans of Todd Haynes’ head-twisting piece I’m Not There from 2007.

What we can say is that Wald’s serious account of this groundbreaking episode is amplifying, illuminating and occasionally electrifying. Perhaps the artist at the very centre of the drama, who was certainly so much younger then, now knows rather more about that sequence of controversies having reading this set text than he was able to piece together himself on that frantic, fateful evening.

Marvelous take on the film and on Wald's book. Can't wait to see the film. The title is brilliantly chosen.

compelling eye to the new BD flick!