Book review #39: Travelling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell

Was singer's beret 'satire on the Beats'?

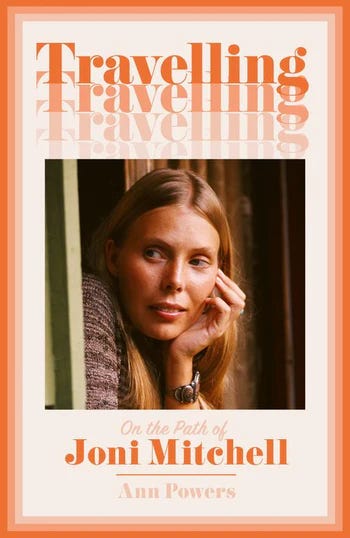

Travelling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers (HarperCollins, 2024)

By Nancy M. Grace

THIS STORY might be anecdotal but it has been reported that Joni Mitchell, irritated by the regular proposal that she was ‘the female Bob Dylan’, pointed out that no one ever called her assumed rival ‘the male Joni Mitchell’. Setting aside the sexist assumptions of much rock music, no one can dispute that Mitchell is a towering figure in American popular music in her own right.

Her life and her art have attracted a number of biographical studies. However, in this review of Travelling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell, Ann Powers’ recently-published portrait of the singer-songwriter, I want to frame my account in relation to her links to Beat artists, particularly women writers and poets from that literary community, figures who are referenced in this author’s account.

Clearly, as the book title itself suggests, there are commonalities to consider. Travel, yes: physically, emotionally, spiritually, sexually, politically, racially, geographically and creatively. But those categories are not unique to Beat culture or to pre-mid-century US and other cultures. Humans have always travelled the many roads that constitute our character.

Like those of the Beat writers, Mitchell’s life and work mirrored and were important to post-World War II countercultures, which led to a more democratic and justice-focused twentieth-century American goliath. Her world was saturated with politics, populism and poignancy that influenced many artists and others, an epiphenomenon of sorts.

So what is the significance of Powers’ contribution to the Mitchell canon? Powers, a well-known popular music critic for NPR, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times, has positioned herself to reveal what has eluded others.

First, and to her credit, Powers makes no claim that Mitchell was directly influenced by any Beat artists, although some have compared Mitchell’s ‘on the road’ composition processes to Jack Kerouac’s, based on her claim that she wrote Hejira while travelling across the US.

But there were actual instances of Mitchell associating with Beat individuals and colleagues, such as her visit with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the Buddhist founder of Naropa University, along with Diane di Prima, Anne Waldman and Allen Ginsberg; and her participation in Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, which also included the participation of Waldman and Ginsberg, though Powers doesn’t mention these.

However, she features experiences that Mitchell had in common with women Beats. In this context, in ‘The Secret’ section of her chapter titled ‘The Boys’, an exposition of how Mitchell’s fellow female musicians, including Cass Elliot, Michelle Phillips, Carole King, Mary Travers and Carly Simon, were secretly ‘half boys’ will be of most interest.

Powers ‘turned to Beat women’ because Mitchell had what the biographer considers a Beat period in high school. Similarly to the Kerouac composition claim, although a bit more credibly, Powers supports her Beat turn with the simple statement that Mitchell wore a beret, the derogatory beatnik stereotype created by the San Francisco journalist Herb Caen – not a genuine Beat affect.

How this grounds an exploration of Beat women as compatriots is confusing since, in her earlier discussion of Mitchell’s adolescence, she notes that the performer’s beret was ‘a satire on the Beats’. But, instead of taking Mitchell at her word, Powers wants to believe that Mitchell’s teenage behaviour actually cloaked admiration, especially when combined with her fascination for what Powers labels ‘slumming’ and describes as ‘the enticing perfume of reefer and racial intermingling’ (70).

Since there’s little to back this up, other than Powers’ reading between the lines, readers are left with an unnecessary gap and the knowledge that some teenagers are capable of expressing dislike through satire.1

The author adds that the Beat link made sense to her because the male artists who Mitchell was hanging out with during her Laurel Canyon years ‘stood upon ground the Beats first trampled’, a half-truth at best, since male Beats drew often and sometimes transparently from centuries of bohemian culture (123).

Powers provides no evidence to the ‘trampled’ territory claim, for either the male Beats or the Laurel Canyon guys. The unstated assumption is that Beat women, as members of a ‘boy gang’, were victims (‘chicks’ or ‘old ladies’) of Beat men who kept them from nurturing their true and independent selves.

The evidence Powers relies upon to substantiate her Beat thesis is equally weak. It consists of a a Diane di Prima line about freeing herself of female stereotypes in her memoir Recollections of My Life as a Woman and a somewhat lengthier discussion of Joyce Johnson’s Minor Characters, in which Powers – not Johnson – sums up Kerouac as ‘messy’, emphasising that he hated women because he didn’t sleep with Johnson after having sex with her.

There’s also a brief mention that Mitchell attended the same folk clubs as did Johnson and that Johnson learned early in life that women had to guard their virginity. The discussion is followed with a description from di Prima of Mary Travers as ‘the ideal' feminine ‘Beat girl’, and an opaque five-word, throwaway (‘We lived outside, as if’) from Hettie Jones’ memoir How I Became Hettie Jones about her Beat life and marriage to the poet LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka). Any form of domesticity, including motherhood, emerges as an anathema in its invisibility.

Like the book itself, the discussion is pop-culturally breezy and often non-contextualized. Mitchell ignores or wasn’t aware of Johnson’s consistent iteration of Kerouac’s support of her own, and eventually successful, efforts to be a writer, the way in which di Prima’s own Italian family force-fed her feminine subservience, which she rejected, and the fact that Hettie Jones was disowned by her Jewish family for having an intimate relationship with Jones, an African American.

Likewise, Mitchell ignores, or was not aware of, other Beat women artists such as Waldman, Joanne Kyger, Ann Charters, Janine Pommy Vega and ruth weiss who were supported in their independence and artistic development by men – Beats, academics, and others.

Then, too, there’s Powers’ bizarre claim that women in rock music were almost always white and subordinate (e.g. Grace Slick, Cher, are the exception Powers cites), contrasted with African American women in the soul realm, where Aretha Franklin ruled and ‘rock boys [took] notes from Tina Turner’, gaining ‘expressive power in the church, which fed directly into secular music’ (128).

Considering this section on Beat women as oppressed victims of misogyny, along with the state of racial relations at that time, a reader might express bafflement as Powers’ claim eschews knowledge of the difficulty for all women of breaking into the music business; state laws banning mixed-race marriages at the time and thus troubling interracial relationships (e.g. Hettie Jones, Vertamae Smart-Grovesnor,2 Alene Lee); and the even more onerous efforts black women had/have to make to shape their own lives.

Every one of these women experienced misogyny, some more severe than others, at the personal and systemic level, as women still do, particularly women of color. But their lives were more complex and artistically successful than Powers leads readers to believe. Perhaps more like Mitchell’s than Powers recognizes.

Add Powers’ lack of understanding of Beat culture all-together and the Beat linkage unravels. ‘Hey anybody, wanna play some basketball?’, she flippantly asks, after declaring that Beat/Laurel Canyon men wielded a protective shield – sports, apparently, and basketball, in particular – to sustain the male self.

Women had only virginity, which was meant to be lost. Granted, Kerouac loved baseball and played football in high school and at Columbia, but the reference sounds more like a nod to Jim Carroll’s Basketball Diaries which, as a signal of Beat masculinity, is, unfortunately, off-base. Not all men enter adulthood with the need to follow or play sports.

The most blatant sign, however, is the fact that she devotes three and a half pages in her introduction to Mitchell as a confessional writer but never connects this genre as a literary strategy practised by Beat writers, especially Kerouac and Ginsberg. Her Beat women section fails as well to address their own turn to memoir as a form of confession.

As I’ve noted, there’s a pop culture breeziness, bordering too often on superficiality, to the book’s use of Beat history, which could in theory function effectively – well-written biographies don’t have to be deadly-dull assemblages of minutiae – but here too often results in superficiality, as the jokes frequently fall flat. It’s a mis-style and it’s a breeziness punctuating many aspects of the biography.

This approach can be explained by Powers’ career as a mass media music critic but also by her decision to write a particular form of biography: a hybrid that draws on the technique of mise en abyme in which a text contains a replica of itself, or a double mirroring effect.

Powers does not describe Travelling with these words, but that’s what she’s done. Her efforts to write a more contemporary biography that reveals what’s not yet been revealed, to map unchartered territory, to create a work of recovery (33) in which she is a ‘witness, not a friend’(12), succeeds at times.

But, early on, it becomes an exploratory travelogue of her own life as a shadow of Mitchell within a bohemian frame. Powers’ version of her own feminist memoir, a first-person narrative emerging as she reflects on, describes and analyses the singer. Mitchell mirrors Powers and Powers eventually mirrors Mitchell. Both Mitchell and Powers materialise as characters in this narrative called biography.

We see it in her analysis of the lines ‘Willy is my child, he is my father’, from the love song ‘Willy’ written for Graham Nash, the title drawn from Mitchell’s nickname for her partner. The text turns quickly to Powers’ own confession that she always found the ‘daddy thing’ creepy and didn’t enjoy men being childish, explaining Mitchell’s images as a phenomenon of an older generation that didn’t have feminist handbooks or feminist role models.

Here the mirror reflects a distorted reality of second wave feminism and the hippie generation. While women and the ‘daddy thing’ still exists, Powers sees herself as a ‘New Waver’ and thus superior to Mitchell (139). We see it in her paragraph on another Nash composition, ‘Our House’, a song she finds ‘slightly disturbing’ because the house was really Mitchell’s, not theirs, purchased with her money, not Nash’s (141).

And then she asks of herself, in the guise of communicating with her readers, ‘Am I being unfair [to Nash and Mitchel]?’ The answer reflects her own situation projected onto the reader: ‘Isn’t that what your parents want for you: a good foundation?’ With someone who loves you? We see it in passages in which Powers presents Mitchell’s physical beauty and contrasts it to her own ordinariness (27).

We also see it in her description of her interview with Nash, including the way Mitchell constructed herself as a temptress, bewitching him into undying love at their first meeting. Powers calls it a narrative out of an Arthurian romance, the kind she herself had read and used as a guide to romance in her youth – and assumed that Mitchell probably did as well. Powers sees in her own ordinary youth, one relying on romance novels, the power Mitchell as a young adult harnessed to mesmerise and seduce a heterosexual partner.

At times, Powers senses that she may be veering off track, that she may be on the verge of losing her role as the invisible witness of a life, so she calls her readers and herself back to the reality of biography, as she does in the Nash seduction scene with a media colloquialism: ‘But back to Graham Nash.’ This transition is irritatingly cute, but it’s not as egregious as the effect of two paragraphs that appear in the last third of the book.

Here, Mitchell is in her forties and marries Larry Klein. This is the Mitchell who Powers in the first paragraph says she’s begun to like the best, one happy with a ‘we’ that blends domesticity with a career. And then comes the kicker in the first sentence of the second paragraph. ‘When I wrote that paragraph above, I was idealising’ (296-97). The marriage was actually rocky, the details of which are chronicled in the remainder of the paragraph.

Why though include a fundamentally fake paragraph? To reflect what Powers has wished for in her own life? To see herself in the confessional mode of Mitchell? Perhaps, since both advance the mirroring effect, which, in her conclusion, Powers finally confronts, although fairly obliquely.

Reflecting on her role, or character, of biographer, she claims that one must love their subject in a way that attends to carefulness as well as passion. In this endeavour, she confesses that she’s tried to trace her own vacillations along a spectrum bracketed by those two extremes and to determine why Mitchell’s music has had such a dramatic effect on her.

But Powers did not need her mise en abyme to achieve those goals. The hybrid biography/memoir with its creation of two characters, sometimes in harmonious companionship, sometimes at odds with each other, produces an awkward reality, causing one to question what the book is truly about.

It distracts Powers from the depth of research that readers should expect from a biography of Mitchell, the depth of a newly chartered territory that, in this case, would render Travelling a reliable and thus useful exploration of Beat and other topics relevant to Michell’s life. Some will no doubt enjoy the often off-hand tone of the book and gratefully see themselves mirrored in Mitchell and Powers, but if one is looking for a more nuanced and professional biography, they won’t find it in Travelling.

References

1 Powers credits the quote ‘a satire on the Beats’ to my essay on Kerouac and Mitchell in Kerouac on Record, edited by Simon Warner and Jim Sampas (2018). My use of Mitchell’s recollections is from Robert Enright, ‘Words and Pictures: The Arts of Joni Mitchell’, Border Crossing, 2001, which included his 2000 interview with Mitchell, still accessible online. The passage that I use to open my essay includes Mitchell explaining that at that time she didn’t like to see ‘the underbelly revered’ and didn’t want to imitate it. ‘God know why I longed for the impossible,’ she said (231).

2 Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl, a documentary film produced and directed by Julie Dash, focuses on the life of culinary anthropologist Vertamae Smart-Grovesnor. The film, which features Grovesnor’s connections to Beat artists, is now in the final stages of editing.

Editor’s note: Nancy M. Grace is Professor Emerita at the College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio, USA. Her publications include Girls Who Wore Black: Women Writing the Beat Generation (2002) and Breaking the Rule of Cool: Interviewing and Reading Beat Women Writers (2004), both with Ronna C. Johnson

See also: ‘Beat Soundtrack #6: Nancy M. Grace’, October 29th, 2021

My voyage also began with high school exposure to Beats . I discovered Nausea by Sartre Baudelaire Les Fleures dermal- great woman Charters, WALDMAN, Kygerr, Pommy Vega and ultimate beat babe DiPrima who was a friend and influencer in Zen Francisco during the reanaissance - A Fool thinks he isa wise man- A wise man knows he isa fool