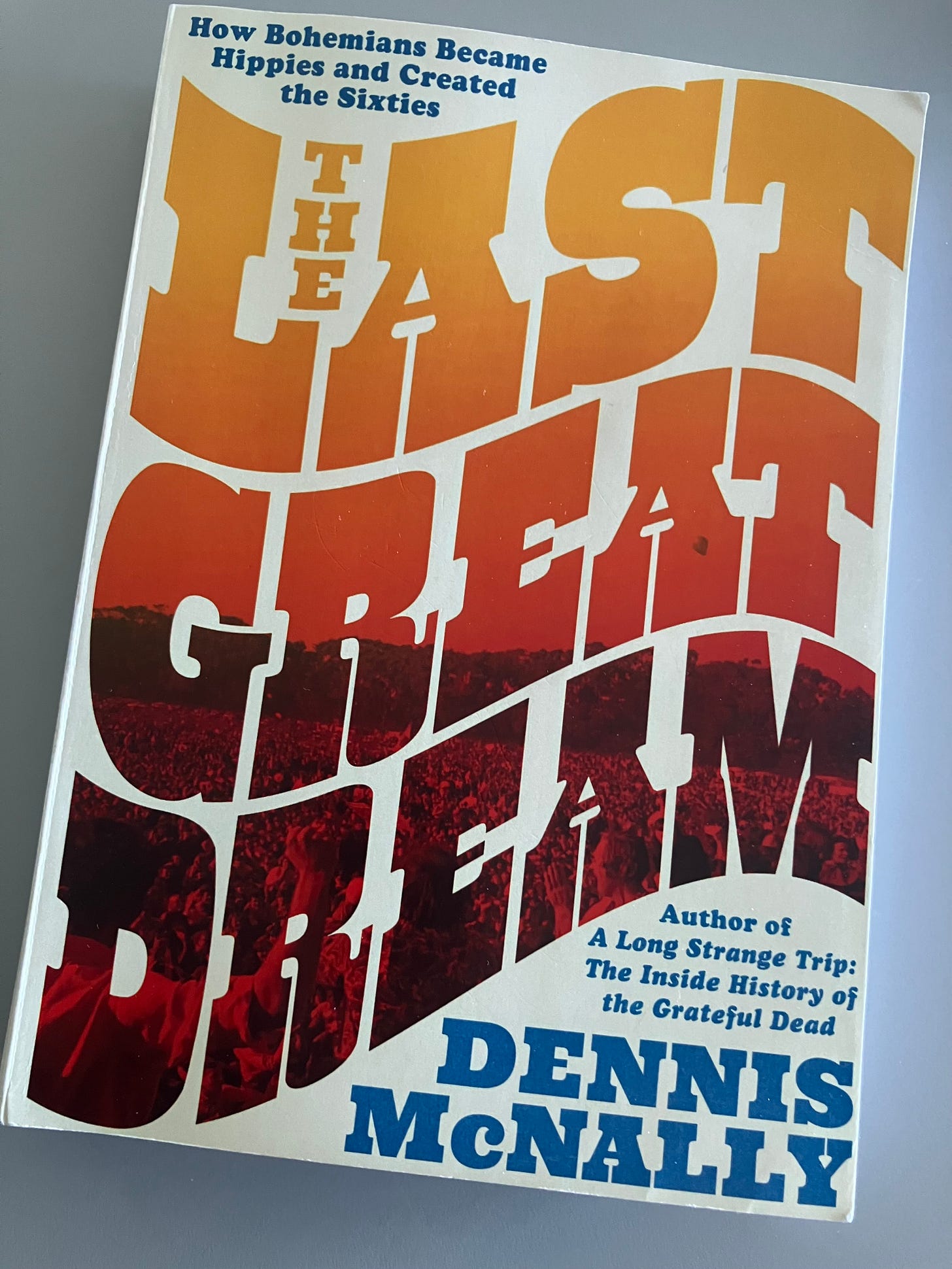

The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties by Dennis McNally (Da Capo, 2025)

By Jonah Raskin

HIPPIES DIDN’T invent ‘ballroom dancing’, not by a long shot. Long before the hippies – ‘the people our parents warned us against’ – populated the Western world, couples had been dancing the jitterbug, the polka, the waltz and more. But stoned hippies with flowers in their hair liberated long established ballrooms in San Francisco, Detroit, New York and elsewhere and danced to rock bands rather than to the big bands of the swing era.

Hippie dancing was the long overdue revenge against the New England Puritans and their descendants who frowned on playing cards and telling fortunes, wearing colorful clothing, dancing around the Maypole and cavorting with Indians. Those activities and others such as smoking dope attracted Sixties hippies who ‘let it all hang out’ and ‘shook their booty’ at the Avalon, Winterland and the Fillmore to name a few of the havens where hippies gathered.

‘Dancing was central to the ballrooms,’ Dennis McNally writes in The Last Great Dream, his dynamic history of the counterculture of the Sixties that challenged racism, the Cold War, the patriarchy and the music of Tin Pan Alley. McNally goes on to offer a telling quotation from Barbara Wohl, a member of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the anarchist theater group which entertained Bay Area audiences all through the era of the psychedelic sounds and beyond.

‘Everyone was dancing,’ Wohl says. ‘Everyone was independent in their dancing, yet everybody danced together. The dancer was equal to the musician on the stage and there was no difference between the performer and the performed upon.’

That sounds like an exaggeration; no one really danced and pranced quite like Mick Jagger or moved as seductively as Tina Turner, but there’s also a kernel of truth in Wohl’s remark. Dancers created their own space and became an integral part of the hippie gestalt. As Sly Stone sang, ‘Everybody is a star.’

It’s unlikely that anyone who reads McNally’s new book will put it aside, get up from a seated position and proceed to dance. But the book has an infectious energy. It may persuade some intrepid readers to ‘dance, dance, dance’ as the Beach Boys sang or take up ‘dancing in the street’ as Martha and the Vandellas put it.

Wohl is one of some 70 individuals that McNally interviewed for his book. The earliest, with impresario Bill Graham and Jerry Garcia, are from the early 1980s. The most recent, with photographer Dennis Hearne, blues man John Lyons, and others date from 2021.

Further, McNally’s bibliography goes on for more than two dozen pages and includes classics such as Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Tests and Michael McClure’s Scratching the Beat Surface, as well as little known gems such as Ray Manzarek’s musical memoir of his life with the Doors, Light My Fire, and Richard Fariña’s irreverent and controversial mid-1960s novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me.

Many of the items in the bibliography draw the reader’s attention to the archives of the Diggers, the theatrical, anarchist group led by non-leaders such as Emmett Grogan, the author of the autobiography, Ringolevio, who died of a heroin overdose on a New York subway train at the age of 35.

The author also offers twenty plus pages featuring a glossary of names: a veritable who's who in the counterculture, bohemia and way beyond, including John Cage, Herbert Huncke, Lenore Kandel and Odetta, the Black folk singer who inspired audiences in the early 1960s. The text provides many of the crucial tunes of the era, from Bob Dylan’s ‘With God on Our Side’ and Harry Belafonte’s ‘Day-0’ to the Who's ‘My Generation’ and The Beatles’ ‘Sgt. Pepper’.

McNally is neither an optimist nor a pessimist. He has his feet on the ground and his head in the world of dreams. ‘A dream captured is already falsified,’ he observes. ‘Only the act of dreaming is authentic.’ He adds that the Sixties ‘dream died, but the dreaming continues.’

The Diggers are the real heroes of The Last Great Dream and the vital link between the bohemians and the hippies. ‘The primary reason for asserting San Francisco as the most influential source of countercultural ideas was the presence of the Diggers, whose critical thinking about freedom and materialism put a certain intellectual spin in the often-vague effect of the San Francisco Scene,’ McNally states in his chapter titled ‘The Diggers and the Love Pageant Rally’.

Other scholars like Todd Gitlin in The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, have touted the Diggers, but no one is more enthusiastic about them than McNally who has spent much of his life in Digger territory and in the world of Bay Area rock bands such as the Grateful Dead.

McNally has a valid argument: the Diggers deserve a lot of credit for helping to create the counterculture in San Francisco in the Sixties. But they are not the only group that helped to define that world. The Beats were a decisive influence as anyone who reads about the 1967 Human Be-In recognizes.

Strangely, the words ‘Beat’ and ‘Beats’ are missing from McNally’s subtitle. Indeed, the Beats came after the bohemians and before the hippies. They are the vital link in the evolution of the cultural revolution. Surely, McNally knows this.

In Chapter 9, ‘The Beats and “Howl”’, he writes that ‘One reason for the ease with which the Beat poets attracted so much (generally ill-informed) media attention was the simple word: Beat; it was a highly effective brand name. Beat, and later beatnik, was an intricate and multilayered coded label that allowed slapdash journalists to pack all manner of connotations into four letters.’

McNally might give too much emphasis to the talismanic words ‘Beat’ and ‘beatnik’ and not enough to the originality and the creativity of Beat literature – Howl and Other Poems, On the Road, Naked Lunch, Memoirs of a Beatnik – and works by Gary Snyder, Philip Lamantia, Michael McClure, Joanne Kyger, Hettie Jones, and others.

Without Ginsberg’s tireless promotion of the work of his friends and himself the Beats might have died an early and a sudden death. Also, without the books themselves Ginsberg would not have had anything to market, publicize and sell.

This historian, the author of Desolate Angel, one of the truly great biographies of Kerouac, may have felt that he had already given more than enough attention to the literary legend and friends and didn’t want to go over the same ground. Additional chapters and information about the Beats would have augmented the power of The Last Great Dream.

Still, this book is one of the very best ever written about the counterculture in San Francisco and beyond. McNally’s chapter titled ‘Hippie in New York’ does an admirable job of explaining why hippiedom didn't take root in the Big Apple, though New York birthed the Yippies, Ed Sanders, the Peace Eye Bookstore, The East Village Other and the Fugs. And, of course, Woodstock was an East Coast thing.

‘The overwhelming energy of New York, the physical sensation of being surrounded by many millions of people, was not conducive to serenity,’ McNally writes. As an ex-New Yorker who was leery of hippies in New York but who became one in San Francisco, I can certainly echo his sentiments. I can also recommend The Last Great Dream without reservations. It's a seriously fun read.

Editor’s note: The Last Great Dream is published on June 5th, 2025

See also: ‘Interview #35: Dennis McNally’, May 1st, 2025

Thoroughly enjoyed your review Jonah! Especially the bit contrasting San Francisco and New York and the way in which you placed `The Last Great Dream' in broader historical context.