Black Surrealist: The Legend of Ted Joans by Steven Belletto (Bloomsbury, 2025)

By Jonah Raskin, Chief Book Reviewer

HOW MANY BLACK Beat poets have there been over the past seven or so decades? And who are they? North Beach’s Bob Kaufman for sure and also New York’s LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), before he became a Black nationalist and when he and Diane di Prima, the author of Memoirs of a Beatnik, were lovers and the editors and publishers of The Floating Bear which put the work of Phil Whalen, Charles Olsen, Robert Creeley and others in print. What about Jack Kerouac, who Ted Joans described as ‘white and Black' and ‘neither white nor black’.

The 'King of the Beats’ might have accepted and even embraced the notion that he was indeed a Black poet. After all, at times he insisted that he wanted to be Black, and in On The Road, his alter ego, Sal Paradise, imagines that he’s a Negro in Denver, Colorado. Joans says that Kerouac was not only a writer but also a ‘poem’. Joans called himself a ‘poem’. Curiously, he argued that Kerouac’s inspiration for On the Road was Langston Hughes’ 1935 short story ‘On the Road’ and that thus the novel had its roots in the lived experiences of Black Americans. That's a possible influence, but unlikely.

What about Joans himself, who was born in Illinois in 1928 to African American parents and raised in a Black family and the Black community? Was he a Black Beat? Joans knew almost all the major Beat figures – Kerouac, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti and Gregory Corso who called him ‘a big professional spade’ who sold his ‘no soul to people for 50 dollars an hour’ (170). Harsh criticism, but it has a kernel of truth.

In the chapter titled ‘The Notorious Rent-a-Beatnik Business’, author Steven Belletto shows how Joans made a modest living in New York by performing as a beatnik and by staging pseudo-beatnik happenings and events mostly for white people. Joans certainly knew how to recognise and read the Zeitgeist and how to ride it for his own benefit.

On various occasions, he claimed that he was an authentic Beat writer and a genuine member of the Beat Generation. Beat academic Bellettto, the author of the new book, Black Surrealist: The Legend of Ted Joans, seems to agree. In a chapter titled ‘The Coming of the Beat Generation’, Belletto, who is white, a major Kerouac scholar and a professor at Lafayette College, insists that Joans ‘was present at the beginning of the Beat Generation’. That’s a stretch. Belletto allows that Joans didn’t actually meet the Beats until the 1950s, when they were already a literary circle, but he argues that in the 1940s he had been ‘a bop hipster’ and that he circulated around some of the ‘hip spots’ on the Beat literary map.

By those standards, Norman Mailer, the author the essay ‘The White Negro’ might be considered a Beat. Mailer frequented Greenwich Village cafes, thought Black people were ‘cool’ and briefly regarded himself as a hipster. In fact, neither Mailer nor Joans were present on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the 1940s when Ginsberg, Kerouac and Burroughs first rendezvous’d, nor were they present in San Francisco in the 1950s when the Beat Generation was busy being born after the Six Gallery reading.

Black Surrealist is the first book about the Illinois-born author of books with titles such as Funky Jazz Poems, The Hipsters, Black Flower Poems – he could certain play with words and phrases – and who also wrote many unpublished works such as Niggers from Outer Space, Spadework and A Black Man’s Guide to Africa, which is part anti-imperialist screed and part handbook for tourists to ‘The Dark Continent’.

Black Surrealist is a welcome addition to the library of modern American literature and culture. Published in 2025, two decades after Joans died at the age of 74 in Vancouver, Canada – the last stop on his whirlwind odyssey that took him from the US to Europe and Africa – Black Surrealist is the product of prodigious research. It offers 60 pages of footnotes, a 15-page bibliography, an extensive index with entries such as ‘Black Surrealist’, ‘the Black Arts Movement’, ‘hypermasculinity’, ‘Negritude’, ‘Charlie Parker’, ‘jazz influence’ and plenty more.

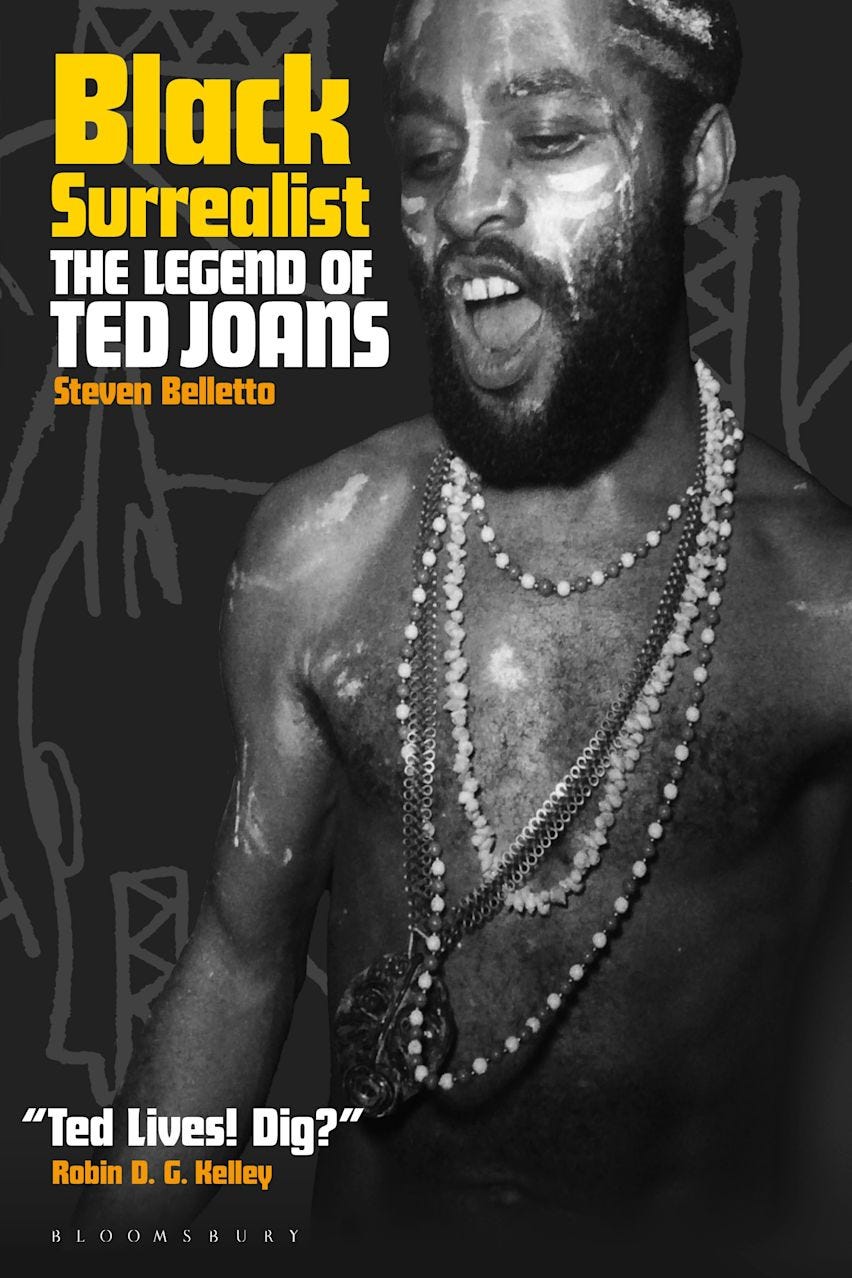

The dozens of illustrations, photographs and pictures of archival material provide a context for Joans’ wild life and untamed art. The cover photo, titled ‘Joans as Mau Mau’, in which he wears beads and is nude from the waist up, seems to be his idea of what the Kenyan rebels against British colonialism looked like. The folks at Bloomsbury are certainly to be applauded for putting together an extraordinary book.

The words ‘birth date change’ appear in the index, but not the words ‘dying and death’. Their absence suggests that Belletto, like Black scholar Robin D. G. Kelley harbours the notion that Joans is alive. ‘Ted Lives!’, Kelley’s blurb for the book reads. (In the 1950s, Joans, a preeminent, notorious graffiti artist, wrote the words ‘Bird Lives!’ on New York City walls after Charlie Parker died. Like ‘Bird’, Joans lives in the hearts and minds of fans.

Black Surrealist is part biography and part hagiography, which the dictionary defines as ‘the writing and critical study of the lives of the saints, or a biography that treats the person with excessive or undue admiration.’ Belletto is certainly adorning and worshipful, though at times he aims to be balanced and to explore Joans’ flops as well as his achievements, his flaws (egocentricity) and his strengths (identification with the oppressed).

He points out that Joans was not, for example, born on the Fourth of July, as he claimed, but on July 20th and that his name at birth was not Ted Joans, but Theodore Jones, Jr. Clearly Jones was far too ordinary a name and July 20th too ordinary a date. After a few serious attempts to nail down the facts, Belletto gives up and allows legends to take over.

On balance the book is perhaps more hagiographical than biographical, but perhaps iconoclastic figures like Joans, who was a legend in his own lifetime, deserve reverential treatment. Belletto rushes in where more traditional Beat biographers like Gerald Nicosia and Ann Charters have declined to tread. As a self-defined ‘self-made man’, Joans was in good company with the Beats.

After all, Ginsberg told Kerouac about one of the manuscripts he was trying to sell: ‘It’s so personal, it’s so full of sex language, so full of local mythological references, I don't know if it would make sense to any publisher.’ Ginsberg could have used the same words to describe Joans’ work. Indeed publishers rejected it because of its obscenities, mythologising and personal references.

Joans himself recognised that he had a ‘factual as well as a fictional life’ and that the reading public wanted to know ‘what was true and the real, or what was surreal and wishful imagination’. He wanted it both real and surreal and so does Belletto, which means that his book will disappoint fact-minded audiences, but delight myth makers who crave books that blur the lines between fiction and non-fiction.

Still Black Surrealist doesn’t read like a novel. It’s ballasted by facts and historical information, but Joans himself takes on the character of a celluloid hero: a Black Zelig or a Black Forrest Gump. In Zelig, Woody Allen plays an ordinary fellow who wants to be liked and who mimics the characteristics of the dynamic personalities around him. In Forrest Gump, Tom Hanks inhabits the role of an American everyman whose path in life intersects with famous folk. Joans seemed to be everywhere, from Harlem to Paris and Cairo. and at just the right time when things were happening and charismatic figures dominated the stage..

Black Surrealist is perhaps most valuable as an account of what it meant to be a talented African American, artist, poet and jazz performer in a racist society buttressed by white chauvinism that aimed to suppress the Black arts and Black creativity. In the confines of the largely white world of the surrealists, Beats and beatniks, Joans found the space to be himself, though he also seems to have frittered away his talents and increasingly lived what Belletto calls ‘a life in suitcases’.

On the edges of the Black Power movement, he flowered as an anti-imperialist and yet he rarely if ever transcended his sense of himself as an entitled, privileged male who made a habit of seducing white women across three continents, having sex with them and describing sexual relations as a political act. He had at least ten children and didn’t help to raise them. Belleto explains that Joans wanted to help Black people have what he called ‘a total revolution’.

Belletto adds that the ‘liberation of one’s sexuality being central to this goal’. In that regard, he was similar to Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver, the author of Soul on Ice which sold more copies than all of Joans’ books put together and who thought that forcing white women to have sex with him was indeed a revolutionary act.

There will probably not be another book about Joans anytime soon. But, if there is one, the author might focus on Joans’ life in Timbuktu, where he presented himself as an anti-imperialist, at least in his head, and an American tourist and entrepreneur who amassed a vast and valuable collection of the art of the indigenous inhabitants of the continent.

According to Belletto, Joans employed a staff of ‘maids’ when he lived in Timbuktu: one to shop, another to wash his clothes, a third to bake bread, a fourth to clean, a fifth to cook his meals, a sixth to collect buckets of water three times a day and a seventh who did odd jobs like collect the mail.

In 1968, with rebellion raging in Paris, Prague and elsewhere, Joans told a reporter for the Black Muslim newspaper Muhammad Speaks that Timbuktu was ‘a centre of Islam’ and ‘ancient black culture’. What he didn’t say was that it was a destination where he escaped cold European winters, basked in the African sun and lived a surreal life where he was waited on hand and foot like a regal majesty from the mother country. Alas, poor Joans lost his footing and never reached the creative heights of his heroes André Breton, Langston Hughes and Charlie Parker.

Editor’s note: Rock and the Beat Generation will interview Steven Belletto, author of this biography, in the very near future

Morning Simon

Very interesting article.

Great read.

Simon could you check your spam I sent you an email.😊

Malcolm

Fiction & non faction-FACTION Joan’s is an architect o the white negro poet who moves with effortless cool & panache navigating a world where artista lees talented than he bacame celebrities by dint of channeling black culture to represent revolutionary values and ideas. Street cool - Jazz- women derangement of the senses