How bard of the Beat put pen to paper to produce Jack-inspired classic

More than 40 years ago a Canadian tripster travelled to a major Boulder convention with Kerouac at its heart. Ten years ago he sat down to put on record the story of that remarkable personal odyssey

BRIAN Hassett has spent decades wandering the Beat Generation trails in North America and Europe, rapping with the writers, mixing with the movers and shakers and, through a series of acclaimed books, documenting his travels as troubadour, raconteur and all-round scenester.

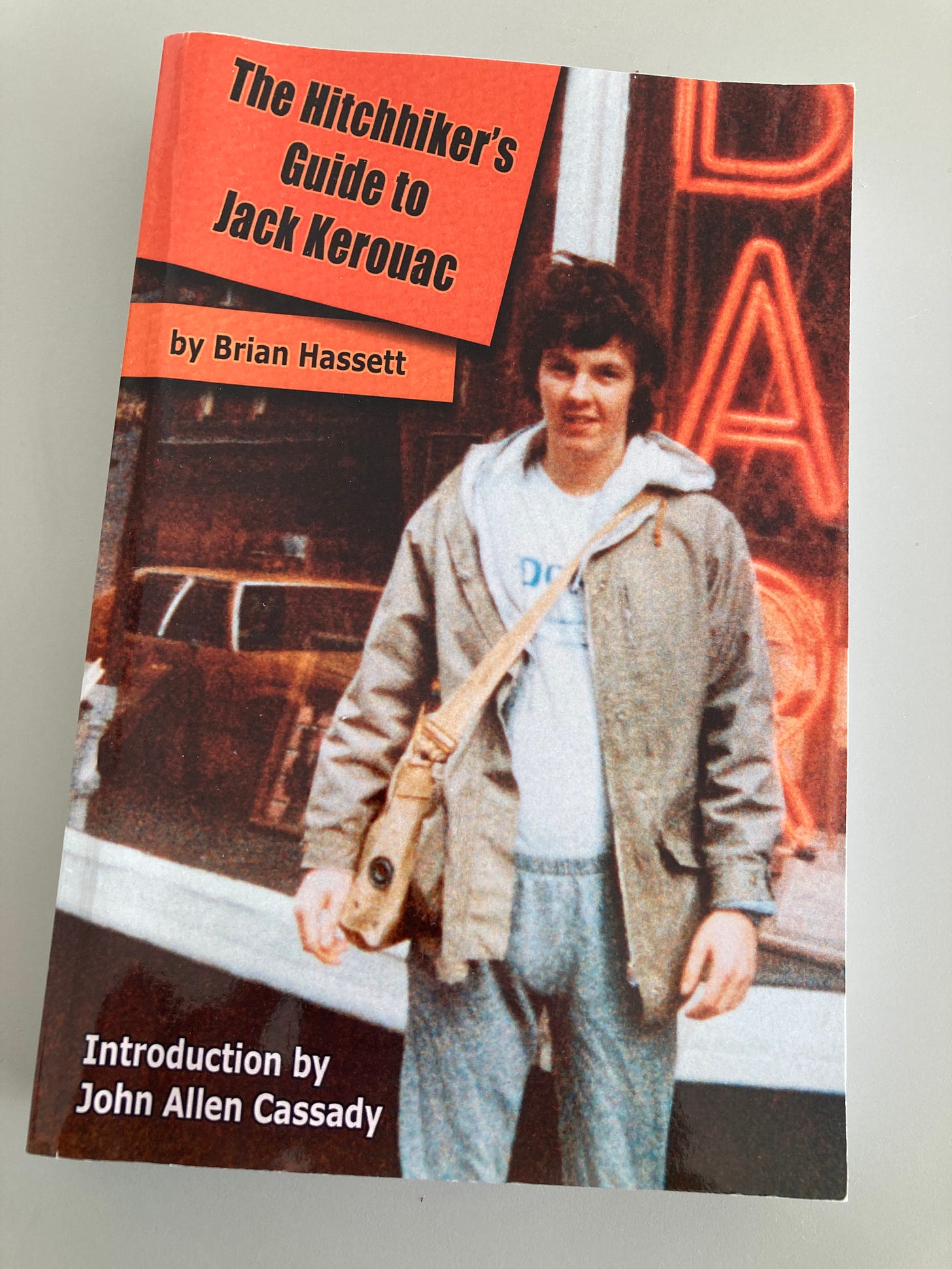

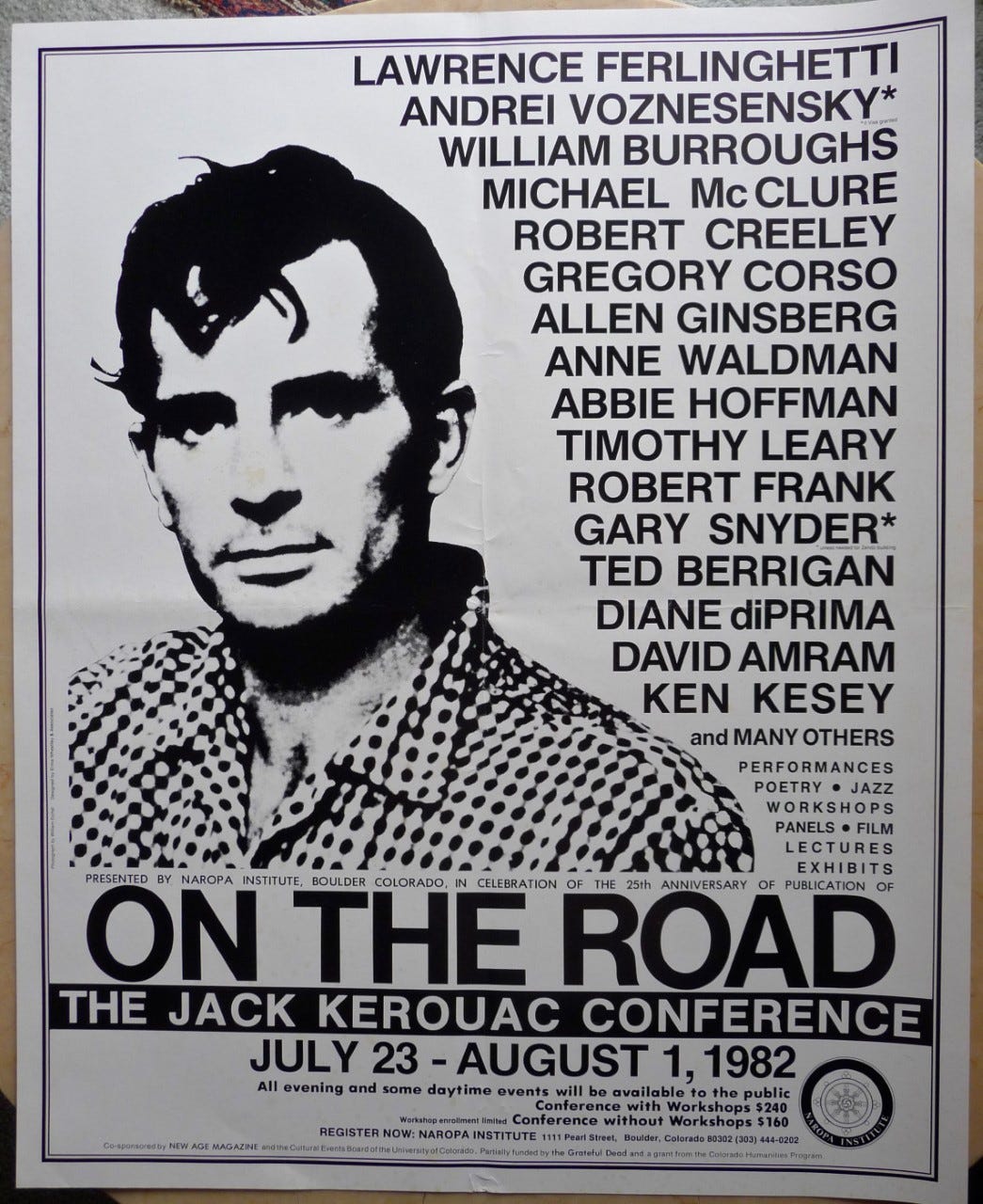

Ten years ago, in 2013, he began his own Duluoz Legend of sorts when he embarked on a book he would entitle The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Jack Kerouac. At the heart of his first autobiographical account was his presence at the 1982 conference in Boulder, Colorado, which commemorated the 25th anniversary of the publication of On the Road and drew a galaxy of Beat heavyweights to a 10-day party.

In bringing this debut memoir to life, Hassett made even Kerouac, that speeding typester and king of the keys – the man who who turned out his classic 1957 novel in an extraordinary three weeks – seem like something of a slacker! Hassett’s homage to his great literary hero was written, start-to-finish, in a mere 11 days and eventually published in 2015.

A decade on, Rock and the Beat Generation fires the questions at Brian Hassett himself about that memorable book and the entertaining escapades of a mercurial existence on the move: the poetry, the music and even the politics of life, the universe and everything…

Greetings, Brian. As we hit the 10th anniversary of you writing The Hitchhiker's Guide to Jack Kerouac we'd love to talk to you about it and the wider inspirations of your life as a wordsmith. One thing I've always wondered about was the title. I don't know how well-known Douglas Adams is on your side of the Atlantic, but his Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy has been a huge influence on two or three generations of British readers. Was it an inspiration to you?

Strangely enough, no. Except for the hitchhiking part. As you probably know, he got the title from The Hitchhiker's Guide to Europe, so mine's just the latest in The Hitchhiker's Guide series.

Well, that succinctly clears that one up! I know your work from The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats back in 1999, but was The Hitchhiker's Guide to Jack Kerouac your first full-length book?

I wrote The Temp Survival Guide (Citadel Press, 1996) about surviving and thriving as a temp worker back in the crazy free-flowing '90s. And I wrote a book similar to Hitchhiker's about the Adventure at the 25th anniversary of Woodstock in 1994 that was finally published for the 50th anniversary in 2019 as Holy Cats! Dream-Catching at Woodstock.

Hitch and the Woodstock book are similar in that they're both epic improbable big-arc true-life Adventure Tales — one ignited by literature and the other by rock n roll. Both were inspired by touchstone cultural events of the not-too-distant past that were re-played out with gusto in the present. Both are about an outsider quickly becoming an insider, and both are told in the language of their inspiration — Hitch with a kind of Kerouacian free-flowing Adventure prose, and Woodstock like the lyrics to songs.

How did you get hooked up with Holly George-Warren's earlier excellent compendium on the Beat Generation? The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats, which came out in 1999, was one of the first publications to really get to grips with that intersection between those writers and our musical heroes, a book that inspired me and I’m certain inspired you…

My girlfriend at the time was an editor at the Village Voice and I was writing a bunch of 'shorts' and 'briefs' — paragraph-long tips on cool bands or things to do in New York. Holly was doing the same thing. And in music journalism there's a kind-of despicable trait of pride in cynicism, this cooler-than-thou arrogance, sort of a race to show who can look down on things more. I couldn't stand it then, and can't stand it now.

But Holly was actually positive — there was a light beaming from her instead of being a black hole that sucks in all beauty and kills it. Holly was effervescent and excited about art and music. THAT's what we're doin' here, man. It's about shining the light, not stomping on flowers. So that was how we connected. We were celebrating the goodness of life all around us — which really wasn't that common in that pretentious world of cynicism. We were just two lightbulbs that noticed each other shining from across the room.

Speaking of lightbulbs, what was the flash that went off in your head that made you feel as if The Hitchhiker's Guide was a book?

I told this story as a 'hidden track' within The Hitchhiker's Guide and then again on my website for the tenth anniversary. (https://brianhassett.com/2023/02/writing-the-hitchhikers-guide-to-jack-kerouac/) It's a crazy-great birth story. It all started with someone posting to an online group that Jerry Aronson photo of a bunch of the original Beats on Allen's front porch in Boulder in 1982.

People were going gaga over so many of them being together in one place, but to me it was just a picture of my summer vacation. People were asking me to share memories of it, so I started to write about it. Pretty soon I realized this was going longer than a comment on a photo: ‘Maybe this should be its own post.’ Then it kept going and I realized it was more than a social media post: ‘This has gotta be its own page on my website.’ Then a day or so later — ‘This is a book!’

Pictured above: The young Brian Hassett features on the book cover

I read a lot of nonfiction and I hate it when authors repeat themselves, and I think that comes from them writing the book over many months and they forget that they've already said something. Or that the tone or tempo changes. Like, at one point the sentences are really sharp and snappy, then the next chapter is lugubrious and ponderous.

When I got the contract to write the Temp book, I wanted it to have a consistent flow and tone, and not repeat itself, so one of my internal directives was to write it fast. You can remember what you wrote two days ago, but maybe not eight months ago. So I wrote it really fast. I wanted to write it in a week, and I did it in six days.

This time, once I realized on day three or so that the Boulder Adventure was gonna be a book, I wanted to match the Temp book and have it done in a week. But I kept finding new notebooks and tapes and folders of material and then it became, ‘Alright, make sure it's done in ten days.’ It turned out to take eleven. But I wrote the whole arc of that book — from first seeing the conference poster in a bookstore in Vancouver to leaving Kesey's farm in Oregon — in eleven days. That's how the voice is consistent throughout — cuz I wrote it all in one continuous flow.

Pictured above: The poster advertising the 1982 Boulder conference

It does feel that way for the reader, I think. Did you pitch the idea to regular publishers or did you feel that self-publishing was always the best way forward?

Once it was a book, I contacted my literary agent in New York, Janet Rosen at Sheree Bykofsky & Associates, who I'd met through David Stanford when he was the editor at Viking–Pengiun. She coached me through the whole book proposal routine and was shopping it around for a while and there was interest but ultimately it came down to — I had no 'platform’. Publishers by 2013 when all this was going down wanted authors with a million Twitter followers or their own TV show or something.

Then this wild thing happened — after about a year of her trying to sell it, I started to look into self-publishing. It seemed like CreateSpace (now KDP), the Amazon subsidiary, was the go-to place. So, I waited one more week to see if any news came in, then finally called them on a Friday afternoon. It was funny — the lady asked what stage the book was at, and when I said it was finished there was this surprised, ‘Oh!’ I think most of their inquiries come from people who are thinking of writing a book.

So, she starts pitching me their services — how much to do a cover, and various editorial services — and then I asked, ‘How much does it cost if I don't use any of those services?’ ‘Oh, well then it's free.’ WHAT?!?! I would pay money to have someone not mess with my book! I can't freakin stand 'house style' or having some desk jockey tell me how my brush strokes should look. I know what I'm doing. I know how I want my artwork to work.

You're a music guy — I used to write music on a staff — I'm very aware of quarter notes, whole notes, rests ... I know how I want my prose to read — particularly the tone and the tempo — the key and the meter. And I know when and how and why to break rules. When the great Jeff Beck died a couple months ago, a quote of his that circulated around was — ‘If I don't break the rules ten times in every song, I'm not doing my job properly.’

All the writers I enjoy the most and inspired me to create in the written form had very particular and unique styles — their work wasn't all genericized by house style copyeditors. Whitman, Thoreau, Twain, Joyce, Jack, Hunter, Kinky. And of course Jack's problems with editors is well documented including the clause in all his post Road contracts that his prose couldn't be touched.

It's like someone saying to Van Gogh, ‘Yeah, we'll publish your painting, but we're just gonna clean up all these brushstrokes.’ Or saying to Dizzy, ‘We like your song about “Salt Peanuts” but we're going to slow the tempo and put in some strings.’ No. You either like the work of art or you don't. You don't get to change it.

Anyway, right after that head-exploding Friday afternoon phone call and I found out I could do it myself, the book got accepted by a publisher in L.A.! But I had just learned that I could publish this badboy myself and control every aspect of it. So, when they accepted it, I asked if I could keep control of the digital file it would be printed from, and they were like, ‘Of course not.’ And this was a very hip publishing house.

At this point I'd been tweaking the book for a while and it read exactly how it was supposed to. I'll be damned if I'm gonna let some person read it once and think they know more about its flow and style than I do. So that's how I happily ended up in the self-publishing world. Someone can like or not like my books, but at least the brush strokes are as I painted them.

How has the web impacted your writing process? Have you always viewed it as a great opportunity?

Well, yeah. Hitch just celebrated its 10th anniversary, but my website just had its 15th! It was actually Levi Asher's LitKicks site on the Beats where the lightbulb first went on for me in 1994-ish. And the WELL — the Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link — remember that one? It was a forum message board out of the Bay Area, and when Jerry Garcia died in the summer of '95, that was the first time there was an event that I could participate in in-person at the Imagine circle in Strawberry Field in Central Park ... and then come home and read other people's experiences from all over the world. That was a real eye-opener.

I'd been reading about the web, of course — it was this huge tsunami that forecasters were writing about for a while. I first got on through AOL like millions of others. I'd been reading about these things called 'hyperlinks' and I remember the first time I saw one — it could have been on LitKicks — where a word was in blue, and if you clicked on it, it took you to another page that dug deeper into that subject. ‘Ohhh ... THAT's what this is! This is gonna be GREAT!’

Up to that point, you'd be reading an article in a newspaper or a sentence in a book and you'd want to go look something up that it was referring to. I had the most incredible home library in New York. I prided myself that I could answer any question that came up with a book I had on hand. And now the internet was replacing that whole process of having to put down the book you're reading and go pull some 700-page tome off a shelf to start looking something up. Suddenly all the background information was one click away. That changed everything.

And then the fact you could dialogue with people you didn't know all around the world. Deadheads were always big on sharing stories and tips and information — and so we all took to it like kids to candy. Then there was that BEAT-L message board created by the great Bill Gargan for all us beatniks to be able to gather in one place. Then of course that infamously flamed out, but it was the beginning of the online interaction that like-minded Beat people could participate in.

Living in Manhattan was like real-life social media in that you were always meeting people from all over the world who were sharing really cool perspectives and ideas. I always carried a notebook every night I went out because people were always sharing great tips of books to read or music to hear or movies to see. Now, you can sit at home and be engaged in the most interesting literary salons the world has ever known — and you don't have to get out of bed!

As we’ve mentioned, the central event of your Hitchhiker's Guide is the remarkable 1982 conference in Boulder, Colorado, where the extended Beat family gathered to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the publication of On the Road. Obviously, the man at the centre of that could not be there, having died in 1969. How did that gathering affect you as a young man, and how was Kerouac's absence felt, do you think?

Well, that event changed the trajectory of my life. It took a 400-page book to even scratch the surface. The way I look at it is — he was there. That's the magic of art — that it lives on. There's a brilliant scene about this in the new cinematic masterpiece Babylon where a writer (played by Jean Smart) explains to an actor (Brad Pitt) how he will be immortal because people who aren't even born yet will be able to experience his creations 50 or 100 years from now. Jack is still alive any time any person reads one of his books. My house is full of Van Gogh prints. He ain't dead. I look at him every day. John Lennon is in my blood. Every word I'm speaking to you today is coming from a part of him.

We're only here for a short time — so create as much art as you can and it will long outlast your mortal coil. Jerry Garcia is still playing guitar. Some movie you saw didn't just play for the two hours you watched it — it's still playing over and over in your soul. All art is eternal and stays with us forever whether the artist still happens to be alive or not.

You've written two other books about the Beats since The Hitchhiker's Guide and seem to live your life as a travelling troubadour, author on the run, spreading your stories and adventures through both performances and on the page. Do you feel as if you're carrying forward the Beat torch in some way?

Well, of course. I just heard this great line in the biopic Barry about a young Barack Obama coming to New York. In fact Jack Kerouac is actually namechecked in it as an inspiration that Obama is chasing. But the Barack character meets a social activist elder who says to him, ‘You carry the baton from the ones who have come before, and you carry it as far as you can, and then you hand it off.’ I'm very aware that yesterday I was a hot happening kid on the scene grabbing the baton from my heroes, and now to many I'm an elder. People tell me all the time that I inspire them in a torch-carrying way. My current ‘Jack on Film’ stage collaborator, Julian Ortman, is 27 years old. My Jack & Neal stage partner, George Walker, is 82 and is constantly telling me how I inspire him.

I'm carrying the torch that Allen Ginsberg and Ken Kesey touched off to me in 1982, and I've been tapping my flame to anyone who has an interest in being lit up ever since. It's one continuous flow. Kerouac didn't start it. He just grabbed the baton from Walt Whitman and Jack London and Thomas Wolfe and Charlie Parker and ran with it for a few years. Allen and Kesey were both very conscious of this. They both knew The Power of the Collective and spent their whole lives lighting unlit torches in others' hands so the flame could keep glowing and growing.

Me as an Englishman and you as a Canadian share a curious historical link through our Britishness. How has being a Canadian writing about the Beat world worked for you? Do you think being a slight outsider has been a lucky advantage?

Yeah, for sure the outsider perspective is a huge advantage. Kerouac had that blessing too, being basically French-Canadian. I lived in Manhattan for nearly 30 years, so I'm sorta half & half. Think of all the great artists who reflected America in unique and powerful ways because they weren't born there — Alfred Hitchcock, Jerzy Kosinski, Neil Young, Robert Frank — it's a really long list of artists who altered the perspectives of untold millions, especially natural-born Americans. Charlie Chaplin, Milos Forman, John Lennon, Bob Marley, Lorne Michaels ... even if we become American citizens, as I did, you're always looking at it with a few degrees of separation that even a great poet born in Hibbing, Minnesota can never have.

You mentioned Garcia in this chat and you contributed a chapter about the Grateful Dead to my 2018 edited book Kerouac on Record. You and I share a huge interest in both the musical scene and its interaction with the literature we love. What do you think about that relationship?

As I said, I see my prose as musical notes on a staff. I'm very conscious of the rhythm and tone (key) of everything I write. That all comes from music. Obviously music was a driving force in Kerouac's life and work. He doesn't write about plays or movies or paintings — it's always about music. Ginsberg didn't make a point of chumming around with Dennis Hopper or Edward Albee — he beelined straight to the master music-makers. It's the artform with the widest appeal to us humans. A half a million people don't sardine themselves in some muddy field to hear a frickin author read! The biggest bestest theaters for plays hold 2 or 3000 people. And movie theaters are a tenth of that. Music fills football stadiums! So it's no surprise that authors and wordsmiths would dig that universally appealing artform, too.

And I love that some of my favorite musicians & songwriters were also voracious readers — Garcia & Dylan in particular. So there's a real crossover. And of course besides being the name of a literary movement, 'beat' is also a key element of music.

When Kerouac was young he wanted to be like Thomas Wolfe. But as he matured he wanted to write books like Charlie Parker played. Allen often performed while playing a harmonium, and he loved to have musicians accompany him, whether that was the Clash…

…or Paul McCartney.

I love how music works in films, and when authors write rhythmically and build to crescendos. And nobody had the beat like the Beats.

Canada, like the UK, I guess, has contributed unusually, hugely even, to the US rock experience. What do you think about that north-of-the-border influence on music in the States?

Well, obviously Canadians are the superior nationality on the planet, that goes without saying (he says with a smile as he tips back a frosty Moosehead.) The Band, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Gordon Lightfoot, Bruce Cockburn, Rush, Shania Twain, Alanis Morissette, Burton Cummings, Randy Bachman and the Guess Who . . . for one thing, there's nothing to do up here for six months of the year except woodshed your instrument. It's no wonder we create so much great music — there's nothing else to do except shovel snow. I was too busy to write so much as a postcard in Manhattan. Moving up to the hinterlands, I pounded out five books in five years. Those Americans got a real distraction problem down there. It's a wonder they get anything done!

Thank you Brian, for these memories, the books and this conversation, conducted, to paraphrase again our late sci-fi writer Douglas Adams, in the virtual bar at the end the universe. Drink up, sir: it’s time to get back to life’s almost infinite possibilities and think maybe about the next chapter in your ongoing book of dreams. Bon voyage…

Thank you, Marc, for your positive response and thank you, Brian Hassett, for engaging so passionately with the questions.

Cathy Cassady writes: ‘One of my favorites, Simon... both the article and the guest. Brian is one of a kind! I'm so glad you captured him for this piece.’