FEW INDIVIDUALS triangulate better with the themes of this website – the Beats, popular music and poetry – than the British rock journalist and cultural historian Steve Turner, someone who has more than dabbled in all these fields and has quite regularly joined up the connecting dots.

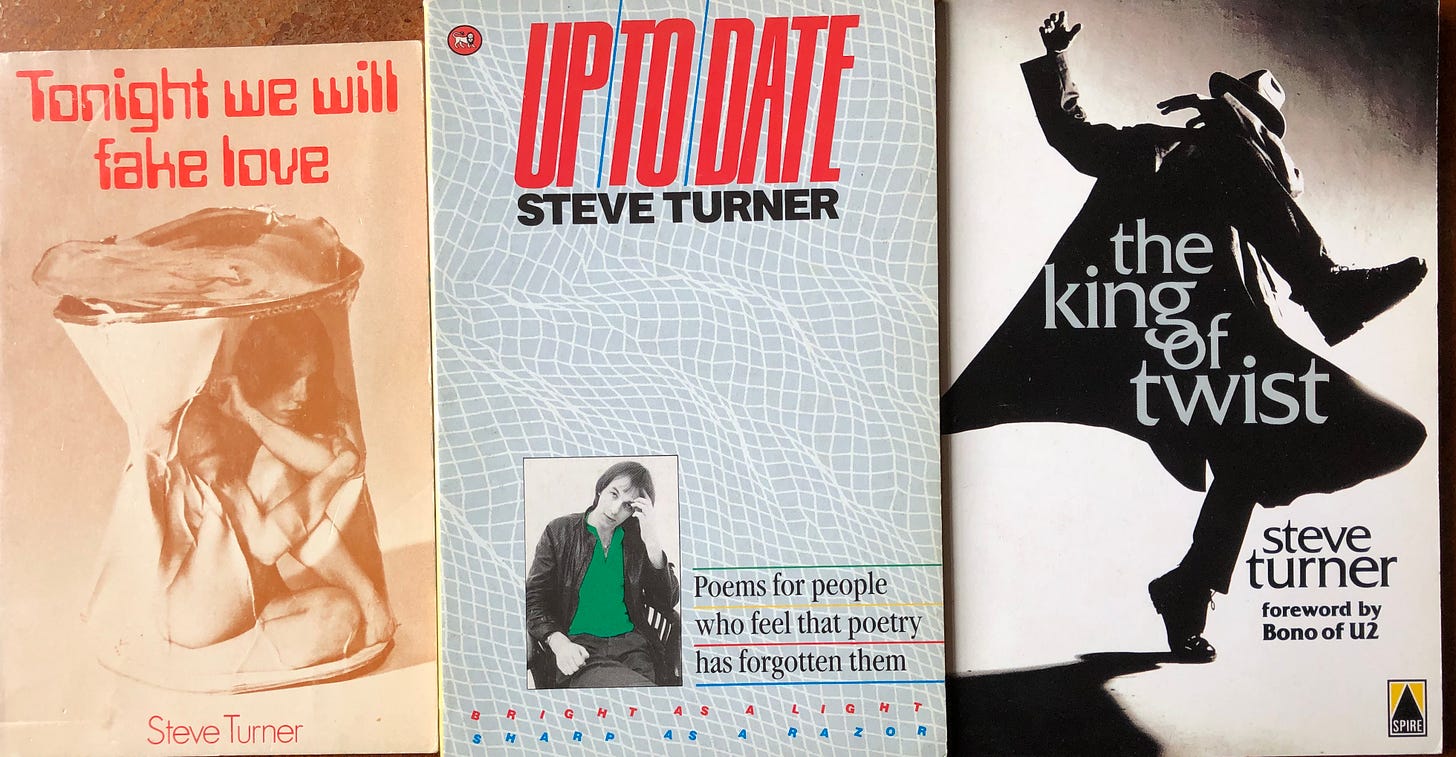

Exactly 50 years ago, Turner, who wrote the highly regarded Kerouac biography Angelheaded Hipster alongside best-selling music titles on the Beatles, Van Morrsion and U2, not only published his first collection of verse but also generated a headline review in the national UK press, his name in lights, some feat for a still-young writer.

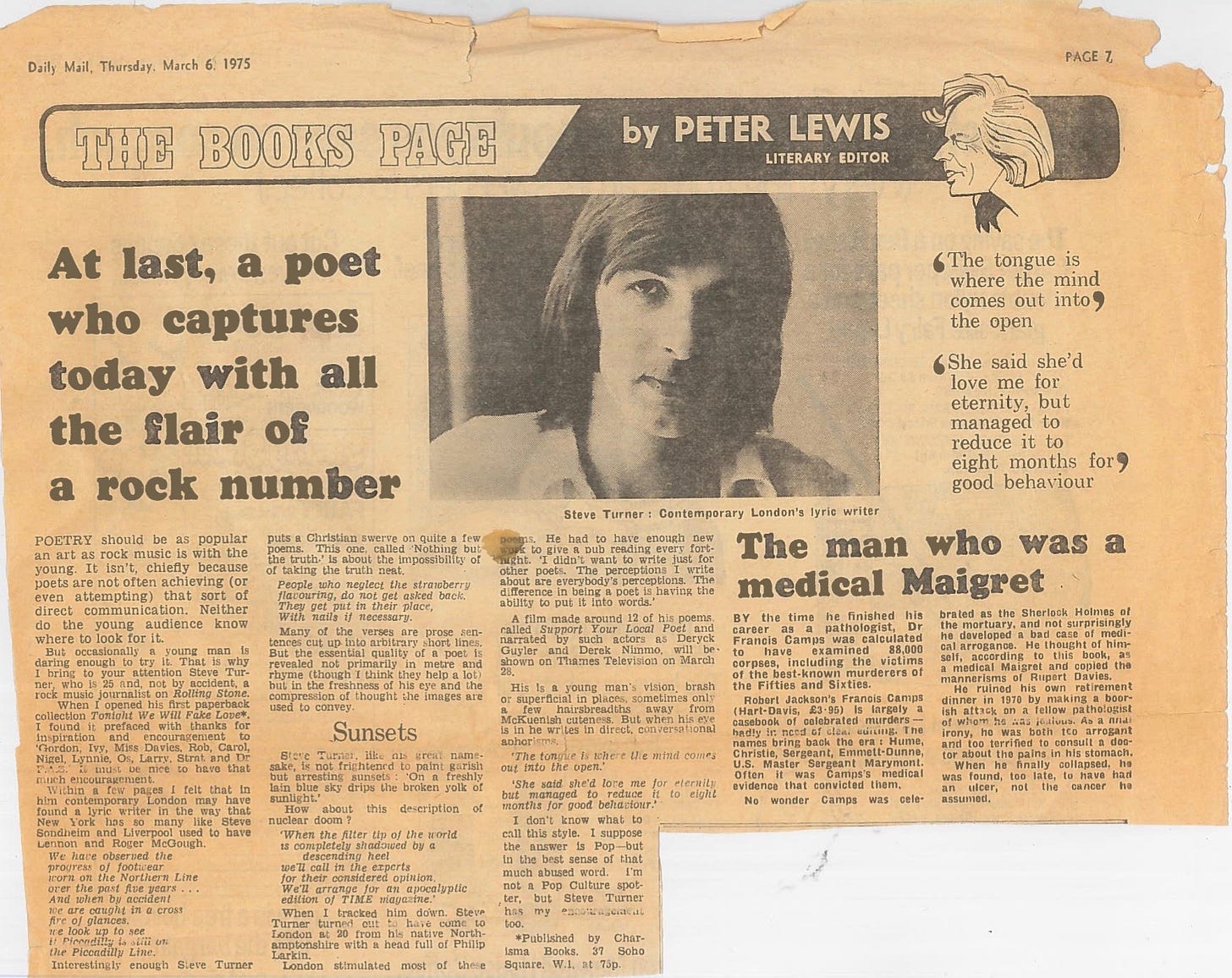

The literary editor of the Daily Mail raved about Tonight We Will Fake Love as the 25-year-old Turner released a collection of poems that had evident links to a number of voices associated with the British pop poetry boom, from London to Edinburgh, Oxford to Liverpool, of the 1960s.

Peter Lewis, in his glowing write-up, made flattering comparisons to Broadway lyricist Stephen Sondheim, Merseyside wordsmith Roger McGough and rock giant John Lennon as he weighed up Turner’s contribution to a new verse scene which was striving to attract younger readers in a language that was lively and informal yet challenging.

Pictured above: Author, journalist, poet Steve Turner

Scanning the Turner lines extracted in Lewis’ notice, I was personally seeing something of Adrian Mitchell, perhaps Michael Horovitz or Lawrence Ferlinghetti even. There was certainly an Anglo-Beat edge to work that employed a certain whimsy to mask deeper meanings.

Half a century on from his media splash, I interview Turner, a one-time scribe for legendary pop inkies NME and MM and currently at work on an epic Beat and rock history entitled Hydrogen Jukebox, about that favourable reception in a high-profile newspaper and his lifelong relationship with poetry and music and the various ways they have overlapped over the decades…

Simon Warner: How did you come to publish this 1975 poetry collection?

Steve Turner: I started writing poems in 1965 and somewhere along the line developed the ambition to have a book published before I was 21. I didn’t quite make that deadline! I used to regularly send work to poetry magazines and had poems published in girls’ magazines like Honey and Cosmopolitan and other publications like the Sunday Times and Rolling Stone.

I read about the formation of Charisma Books in Melody Maker in (I think) 1972. Tony Stratton-Smith of Charisma Records (Genesis, Monty Python, Van der Graaf Generator) formed the company with Leonard Cohen and Cohen’s lawyer Martin Machat in the belief that there were literary equivalents of Neil Young and the Beatles out there. It coincided exactly with my vision.

I sent the poems to Strat (as he was fondly known) and, a couple of weeks later, had a call from him. ‘As you can imagine we a lot of book submissions after that story came out and we can’t publish all of them,’ he said. ‘However, yours is one that we do want to publish.’

I always took what I thought of as a rock‘n’roll approach to the presentation and marketing of my work. All the publicity photos for Tonight We Will Fake Love were taken by Mick Rock, who I loved because of his image of Syd Barrett on the cover of The Madcap Laughs. When I did Nice and Nasty we had T-shirts, posters, envelopes, notepaper and badges using the cover design. The book was illustrated in punkish style by graphic designer Philip Miles.

The King of Twist had a foreword by Bono and was launched with a reading at the Theatre Museum in Covent Garden. On a lot of readings, I was the support act to a folkish musician.

Pictured above: The Daily Mail review of Tonight We Will Fake Love

SW: In your mid-twenties, did you see life as a poet as a career prospect or gateway or merely a sideline to your other writing?

ST: Ideally, I thought I could become a writer who did many forms of writing. I started writing poetry seriously in 1965 but didn’t write a music feature until 1969. In the mid-1970s, I can remember walking along Piccadilly thinking, ‘I’m not sure if I want to be Norman Mailer or Allen Ginsberg.’ How naïve! I certainly thought of myself as a poet who did journalism rather than a journalist who did poetry.

SW: You must have been delighted by the review in the Daily Mail. References to Sondheim, Lennon and McGough must’ve been quite mind blowing…plus television paying you attention. Some entrance!

ST: Yes. I lived near Shepherd’s Market, just off Piccadilly, at the time. I knew that the Mail was going to review the book because they called to ask some background questions, but I wasn’t prepared for the extent of the review and the fact that Lewis highlighted things I intended to achieve.

In January 1969, I wrote my dream review: ‘A sensational volume of poetry,’ it would say. ‘These poems are full of experimentation and drenched in the spirit of today.’ Beneath this I had added: ‘What I would like to do in poetry is what the Beatles and Stones have done in music…’

After I’d bought the Daily Mail that day I just ran three laps of Green Park; it was too much to absorb. I didn’t know who Sondheim was at the time! I wrote to Peter Lewis to ask. Roger McGough reviewed the book for New Musical Express.

I shared my West End flat with three other guys, one of whom was Norman Stone, then a student of film and television at the Royal College of Art. He and I thought alike in so many areas and he needed need to make a film as his final presentation that would showcase his skills as an animator, artist, documentary maker and director of drama. My poems gave him the opportunity.

Vivian Stanshall read one of my poems as did character actors Deryck Guy, Derek Nimmo and Graham Stark. We almost got Sir Alec Guinness. Bond girl Caroline Munro acted in one of the scenes. Norman went on to become a successful filmmaker. He directed the original TV version Shadowlands.

SW: From the title and the extracts, the overall work seems to have the feel of Adrian Henri, Adrian Mitchell, maybe Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Who was driving you to write? Were these some of your inspirations? Was Peter Whitehead’s 1967 documentary Tonight Let’s Make Love in London on your radar?

ST: Certainly I loved those poets and got inspiration from others like T.S. Eliot, Edwin Brock, Jon Silkin, Douglas Dunn, Sylvia Plath, Philip Larkin, Richard Brautigan, Dylan Thomas, John Updike, Richard Fariña and Russell Edson.

I was fortunate to see people like Stevie Smith, W.H. Auden, Yevtushenko, Stephen Spender, Robert Graves and Ted Joans during my first years in London. I used to get books from the library and, if I liked what I read, I’d find out their influences and even the influencers of those influencers. I didn’t see Tonight Let’s Make Love in London but I saw the title and that, plus Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Fakin’ It’ and Roger McGough’s ‘The Act of Love’, were the inspirations behind the poem.

Pictured above: A selection of Turner’s poetry titles

SW: Say a little please about the impact that the Mersey Poets, the Beats and indeed Larkin had on your progress. Was Michael Horovitz one of your early mentors?

ST: I first read about the Mersey Poets in Town magazine in 1967. There was a black-and-white photo of each poet plus one poem by each of them. They really touched me by showing that poetry could be about the recognisable landscape of late 60s Britain with references to rock music, clubs, parties and bedsits.

When I did my first reading in January 1968, I took the style and sentiment of the McGough poem in Town. Afterwards a fellow poet called Brian Ratcliffe commented to me that one of my poems was very close to something McGough had written. I thought he must also have read Town magazine.

That’s when he told me about the Penguin Modern Poets collection The Mersey Sound and Edward Lucie Smith’s The Liverpool Scene. I bought both of those as soon as I could and also Brian Patten’s Little Johnny’s Confession.

Brian Ratcliffe also loaned me the spring 1966 issue of Paris Review with Tom Clark’s interview with Ginsberg that had a big impact on me. I met Brian Patten at a reading at the ICA in October 1968 and we exchanged letters. In May 1969, I was part of a group of poets from Northampton who went up to Liverpool to read at the Samson & Barlow’s restaurant on London Road. Mike Evans, poet and musician of the Liverpool Scene band, was there.

I loved – and still do – Larkin’s poems. I was chuffed in the mid-1970s when I went to the Arts Council Poetry Library that was then in Piccadilly and, when I showed my membership card to librarian Jonathan Barker, he recognised my name and told me that he’d been part of an advisory panel for a planned reading at the Festival Hall and Larkin, also on the panel, had said, ‘Why don’t we have some younger poets – like Steve Turner?’

Mick Brown, now of the Telegraph, wrote a feature for 19 magazine where he interviewed younger artists of various kinds and paired them with an older artist. I was paired with Larkin.

I did a reading for Michael Horovitz at ‘Pentameters’ (Three Horseshoes) in Hampstead with his wife Frances Horovitz and Roger McGough. When Tonight We Will Fake Love came out, I sent Michael a copy and he responded with a long letter (typed on green paper!) in which he critiqued almost all the poems and suggested further reading.

He was a great encourage of people who I saw periodically. He came to see me interview Carolyn Cassady at the British Library in September 2007. I last saw him in 2020 at a launch for a New Departures book by Vanessa Vie. Michael Horovitz died in 2021.

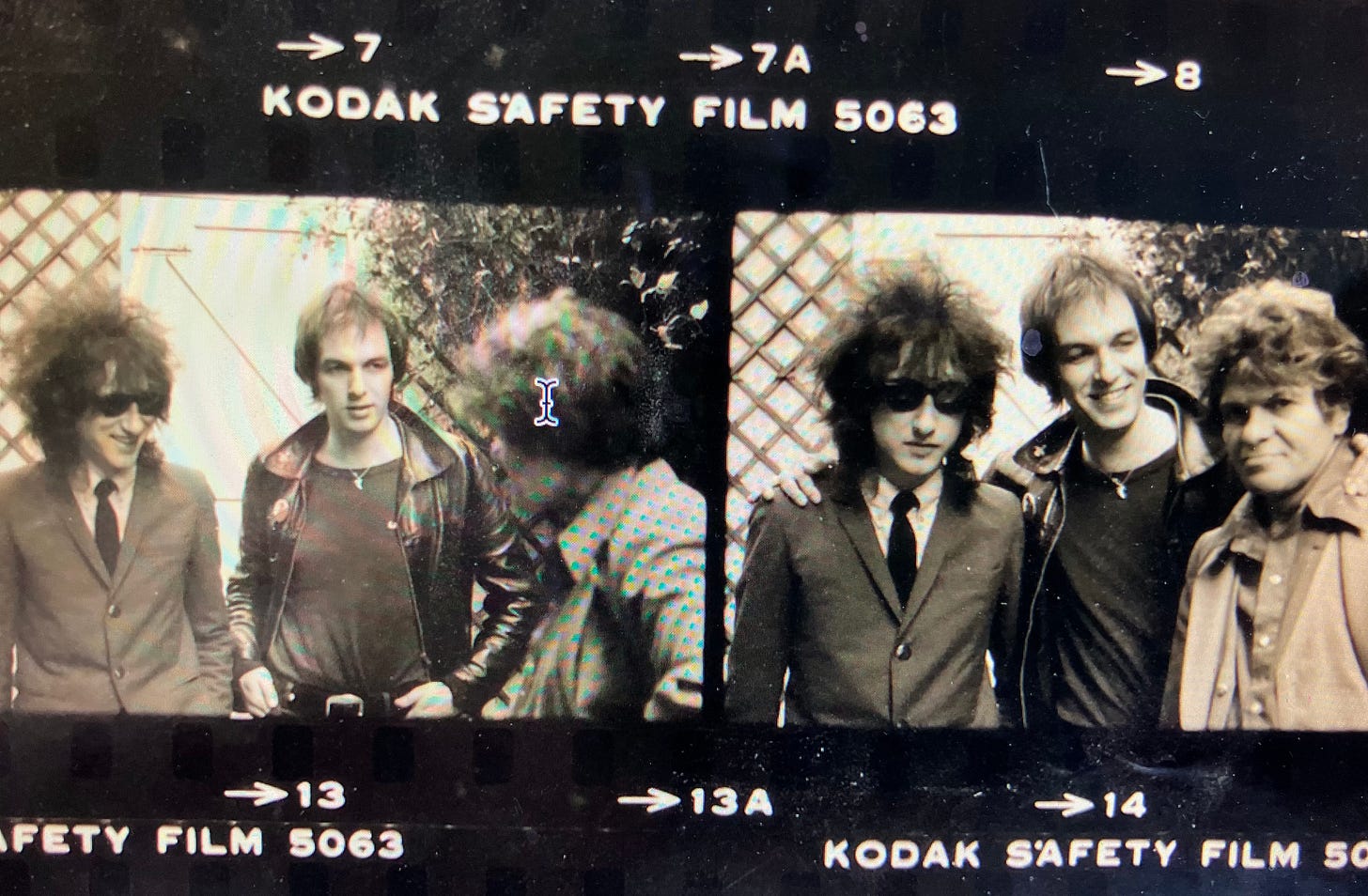

Pictured above: Turner with John Cooper Clarke and Gregory Corso, Chelsea Arts Club, 1980

SW: You have continued to publish prolifically, words and works of all kinds – musical biographies, cultural histories, children’s books. Does poetry remain a passion, an interest?

ST: Yes, poetry is still a passion. I did four books and then got caught up with the children’s poems, five titles in all, after having my own children. I recently completed a new adult poetry book called Too Much Is Not Enough, in which every poem is a response to a passage in Ecclesiastes. I have great blurbs from Billy Collins, Ron Whitehead and others and am about to tout it around to publishers. I also have a children’s book ready to go titled I’d Love to Live in a Castle.

SW: What were the links do you think between the new rock culture of the later 1960s and poetry? Were Dylan and Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Ray Davies, poets by virtue of the lyrics they wrote? Did they give you, as a young rock critic, permission to pen and perform poetry?

ST: I always saw the poetry as having a close affinity what was going on in music and I share the idea of people like Rexroth and Ferlinghetti that poetry should come off the library shelves and get down in the streets and basement clubs. The people you mention all loved poetry, had favourite poets and used various poetic techniques in their lyrics but the lyric has the support of guitars, piano, drums, etc., whereas a poem has to have its own inbuilt music

One of the great privileges of interviewing so many rock stars over the past 55 years has been to learn how they craft music and words and also to have had some of them read and appreciate my own poems – Pete Townsend wrote me a poem about my poetry, Paul McCartney called me to tell me how much he’d enjoyed one of my books and Leonard Cohen quoted one of my poems to me in response to one of my questions to him.

Lyrics prior to the rock revolution – e.g. the Great American Songbook – were also inspired by poetry, often very witty, intelligent and playful. I enjoy the songs performed by Frank Sinatra as well as the songs from musicals and the British music hall of the 19th century. There is a danger in thinking that popular music was unaffected by poetry until Bob Dylan discovered Rimbaud and Blake, but this isn’t so.

SW: Peter Lewis, the reviewer of your book, mentions ‘a Christian swerve’ to some of your 1975 poems. How have issues of the spiritual shaped your writing and your life? You wrote Hungry for Heaven, an acclaimed account the relationship between religion and popular music. You also, in your 1996 Kerouac biography, drew attention to the significant part Western and Oriental faith had on so many of the Beat novelists and poets. How has this alchemy presented itself?

ST: Though I didn’t plan it this way, all the artists I’ve written about in depth – Johnny Cash, U2, the Who, the Beatles, Marvin Gaye, Van Morrison, Kerouac– have explored issues of faith.

My Christian beliefs shaped my priorities just as Ginsberg’s Buddhist outlook shaped his. For me, the Beats, and songwriters like Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan, helped validate poetry that reached out beyond the mundane. Ferlinghetti wasn’t friendly towards the Christian faith but, even so, he dealt with Jesus. Corso had a vestigial Catholicism. And Kerouac was caught in a struggle between his fleshly passions and the faith of his childhood.

SW: Is there is still an idea of pop poetry or rock verse in 2025? Kae Tempest Anthony Szmierek come to mind, so does John Cooper Clarke, an enduring figure, also Linton Kwesi Johnson a significant presence, and we should certainly mention Benjamin Zephaniah, a recent and sad loss. They have all married verse to musical soundtracks. Does this kind of overlap interest you? You talk about regular live pub sets of your poetry in the Mail article. Did you feel you were part of a spoken word tradition when you stood up to read?

I was always interested in the relationship between rock music and poetry. I brought John Cooper Clarke and Linton Kwesi Johnson together at my flat in London in July 1979 for a joint interview that became a cover story for Melody Maker. I also met John with Gregory Corso at the Chelsea Arts Club in September 1980.

In 1980, I recorded three poetry/music tracks with T Bone Burnett in LA that featured Steven Soles and David Mansfield (Rolling Thunder Revue) on guitars and Jerry Scheff (Elvis Presley) on bass.

Also, I did a whole (unreleased) album of poems and music in 1981 with musician Nick Battle and producer Simon Humphrey. We did one live show together at the Young Vic which I found terrifying because we hadn’t rehearsed! I always felt part of the spoken word tradition that started with Dylan Thomas and the Beats and which was flourishing when I came to London in 1970.

See also: ‘Biographical Details #1: Jack Kerouac by Steve Turner’, September 30th, 2023; ‘Beat Meetings #2: Steve Turner & Herbert Huncke’, March 18th, 2023; ‘Beat Soundtrack #18: Steve Turner’, May 19th, 2022; ‘Interview #5: Steve Turner’, March 6th, 2022

Ferry cross the Mersey -MM NME. MICK ROCK- Angel HeadedHipsters. The globes most. Popular poet John Cooper Clarke. All the proper buzz symbols that represent a generational heritage- to think the aforementioned has been shopped for the Neo fascist Trump World this generation is trapped in soon to be deported to ElSalvador

Marvelous interview. I particularly enjoyed the section on the Mersey poets and his discussion of his encounter with Larkin. Love the title of his forthcoming book.