A GREAT excitement for Allen Ginsberg was the notion that his work, and Beat work generally, was having a trans-generational impact: the stanzas, the paragraphs, the verbal interactions, on the page, on stage and in recordings, were being consumed and enjoyed and utilised by those who followed in the wake of his unique clan of poets and novelists. He dug the fact that musicians like McCartney, Patti Smith, Thurston Moore, Cobain and KRS One had tuned in.

And let us say that if Ginsberg’s own epic statement ‘Howl’ was born of a particular moment – a grey America, a cold America, a repressed America, fearful of itself and those beyond itself – its material, often anxious, alienated, angry, was not merely a critique of the mid-1950s setting.

Its visions were bigger and bolder, its ideas neither time nor place specific: the Zeitgeist breathed through its bellowing lungs. This magnificent Babel verse, stacked several storeys high, hoped that the outsider – racially, spiritually, economically, sexually – might eventually inherit something.

In the decade after that poem was first read, initially published and then sturdily shook off charges of obscenity before a San Francisco judge, Ginsberg’s explosive account would catch the ear of hundreds of thousands of younger listeners and readers and they would put the essence of Beat – challenging and unsettling but also joyful and releasing – to their own uses and causes.

This particularly happened, of course, within the circles of the new rock fraternity who emerged in the heart of the 1960s. If the raucous and reckless thrills of rock‘n’roll had energised US teenagers around the time that ‘Howl’ was being written, 10 years on a fresh wave of music makers had now combined those earlier visceral sounds with personal manifestos: expanded minds delivering thoughtful commentary and anarchic revelry.

Many of those groundbreaking actors – Bob Dylan and the Beatles, Jerry Garcia, the Velvet Underground and Jim Morrison, David Bowie and Van Morrison among them – had plugged-in to the power of Beat writing to shape a dynamic version of popular music which transcended the adolescent love song and dealt rather with matters of the psyche, the sexual and the political.

One of those potent players was a an LA-based performer called Tim Buckley – a distinctive guitarist with a prodigious vocal manner and range – and his collaborative partner Larry Beckett, initially as drummer and then as inventive lyricist, was certainly absorbing the influence of the new writing, reading Ginsberg and Kerouac with great hunger during these years of shift and transformation.

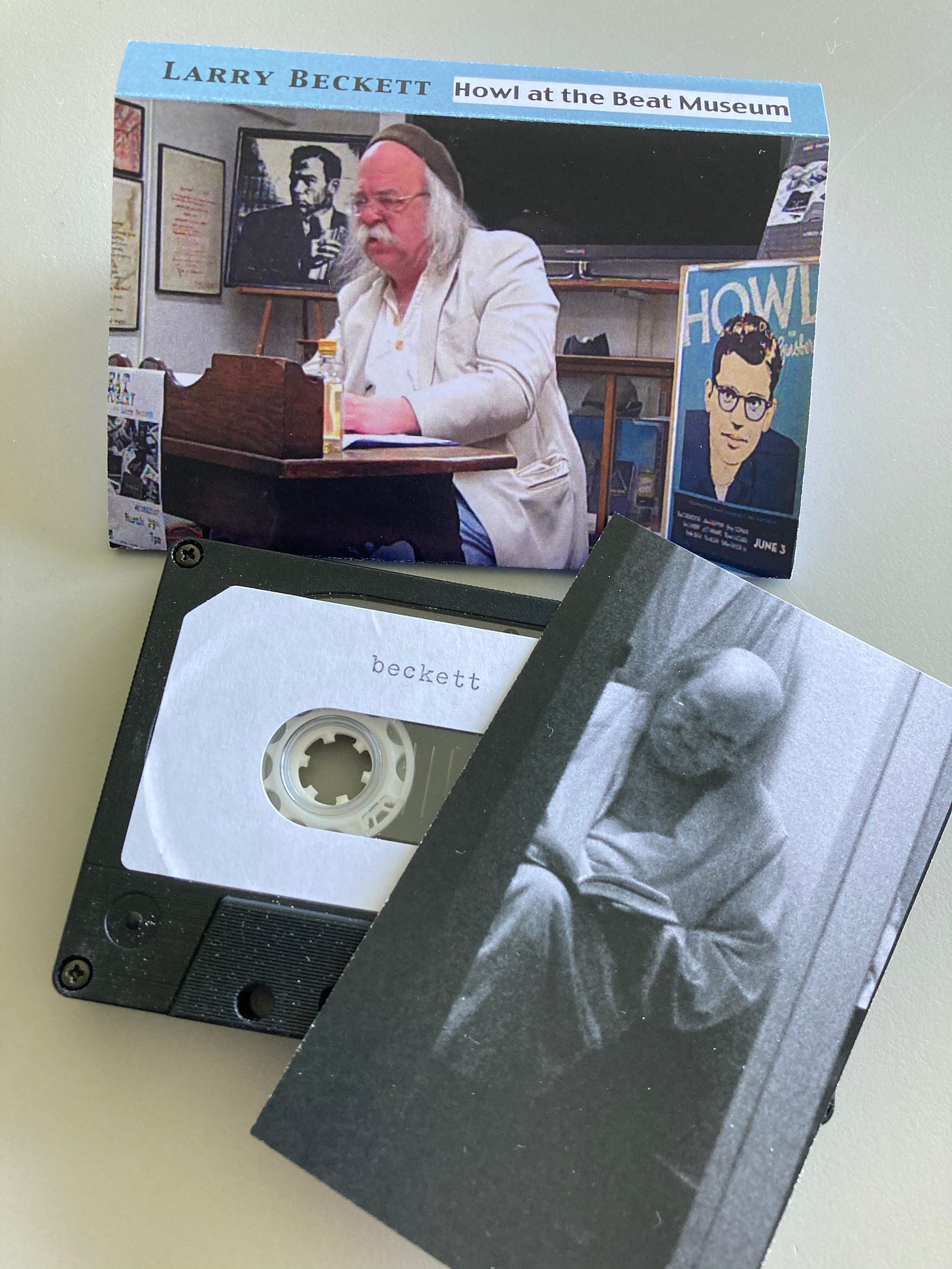

Pictured above: Beckett’s Ginsberg reading taped

Beckett definitely provides a fine example of the trans-generational nature of Beat and the fact that he would go on to spend decades as a poet, long after Buckley had succumbed fatally to the numbing desperation of alcohol and narcotics, only adds to. that powerful notion that a baton had been passed. The rocker reads the writers and then becomes the versifier.

So there is something pertinent indeed about a new release of Beckett reading ‘Howl’ to a live audience at the Beat Museum in San Francisco. Although it has been quite some time arriving – the recording was made back in 2017, some 60 years after the poem had faced its day in court – the results are reassuringly worthwhile.

If we bear in mind that Ginsberg was not even 30 when he stood up in 1955 at the Six Gallery – a reclaimed auto shop in the same city – to give birth to a poem that would perhaps rival ‘The Waste Land’ as the most impactful verse work of the modernist century, it was some feat for one so young to both pen and then declaim so capably such a lengthy and multilayered narrative on stage, even if we only have witness accounts to that – Kerouac and Michael McClure, for instance – as no record exists of the actual debut reading.

His heir Beckett is just short of 70 years as he takes to the lectern for this much later presentation and the maturity and deep sonority of this older man suits the profundity, the gravity, of the interlocking images, the frequent tension of the cracked yet crackling syntax.

In addition to the rendering of the first part of ‘Howl’, the cassette tape, produced by his regular tech ally Paul Walmsley and released by Dutch company Counter Cultural Chronicles, features an extended introduction by the writer himself, commentary on the historic context and references from Beat Poetry, the poet’s own 2012 book about this body of innovative writing, plus a question and answer session with the audience to close.

Is there room for another interpretation of ‘Howl’ when a number of versions by Ginsberg himself exist on disc? I think probably so. I recall having the lasting pleasure of engaging a young actor called George Hunt to read the piece at anniversary events in the UK – Howl for Now in 2005 and Still Howling the 2015 – who proceeded to learn the text in full. Some feat for sure, driven by youthful vim and dedication.

Beckett’s take is sagely, calm, deep: it is his tribute to a hero and you feel that this extraordinary soliloquy – Ginsberg’s massive synthesis of history and myth, of faith and secularity, of dreams and autobiography – is a form of inspirational fuel to any poet who takes it on. The words, the lines, roll on his tongue like mystical nourishment, protein-packed mantras capable of feeding soul and mind in equal measure.

At the start of the live reading, Beckett tells those gathered: ‘Around the corner is a shrine –1010 Montgomery Street – where you can look through the first floor window into the room where Allen Ginsberg wrote the poem.’

In many ways, this re-visiting of an important symbol in the contemporary artistic canon, allows us to look through a window ourselves as an acclaimed poet of today, author of the widely-celebrated epic American Cycle and a figure who clearly venerates the radical literary tradition built on the foundations of ‘Howl’, takes the opportunity in a most suitable venue to reboot a classic text in a respectful manner.

Note: Larry Beckett, ‘Howl’ at the Beat Museum, MC, Counter Cultural Chronicles 123, 2023

See also: ‘Beat Soundtrack #20: Larry Beckett’, June 19th, 2022; ‘Muse and music: Bridging the gap’, May 26th, 2022; ‘Radio date for McGough and Beckett’, January 9th, 2022; ‘Radio review #1: “Song to the Siren”’, December 8th, 2021; ‘Interview #3: Larry Beckett’, November 27th, 2021

It was amazing to hear the recording by Larry Beckett live. I'm so glad that others now have the chance to experience it.

Your descriptions of 'Howl' and the recording make me want to listen again - and I will!

Yay! & don't forget Patti Smith's "Spell" which includes some of the text of Howl as well...(!)