Inspired by madness? Beat, rock and the unstable mind

Psychiatrist's take on mental health & creativity

STEVAN WEINE is an academic psychiatrist and professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, with expertise in trauma and global mental health. Decades ago, when he was a medical student, Allen Ginsberg entrusted him with materials not previously shared, including psychiatric records which documented how he and his mother Naomi Ginsberg struggled with mental illness.

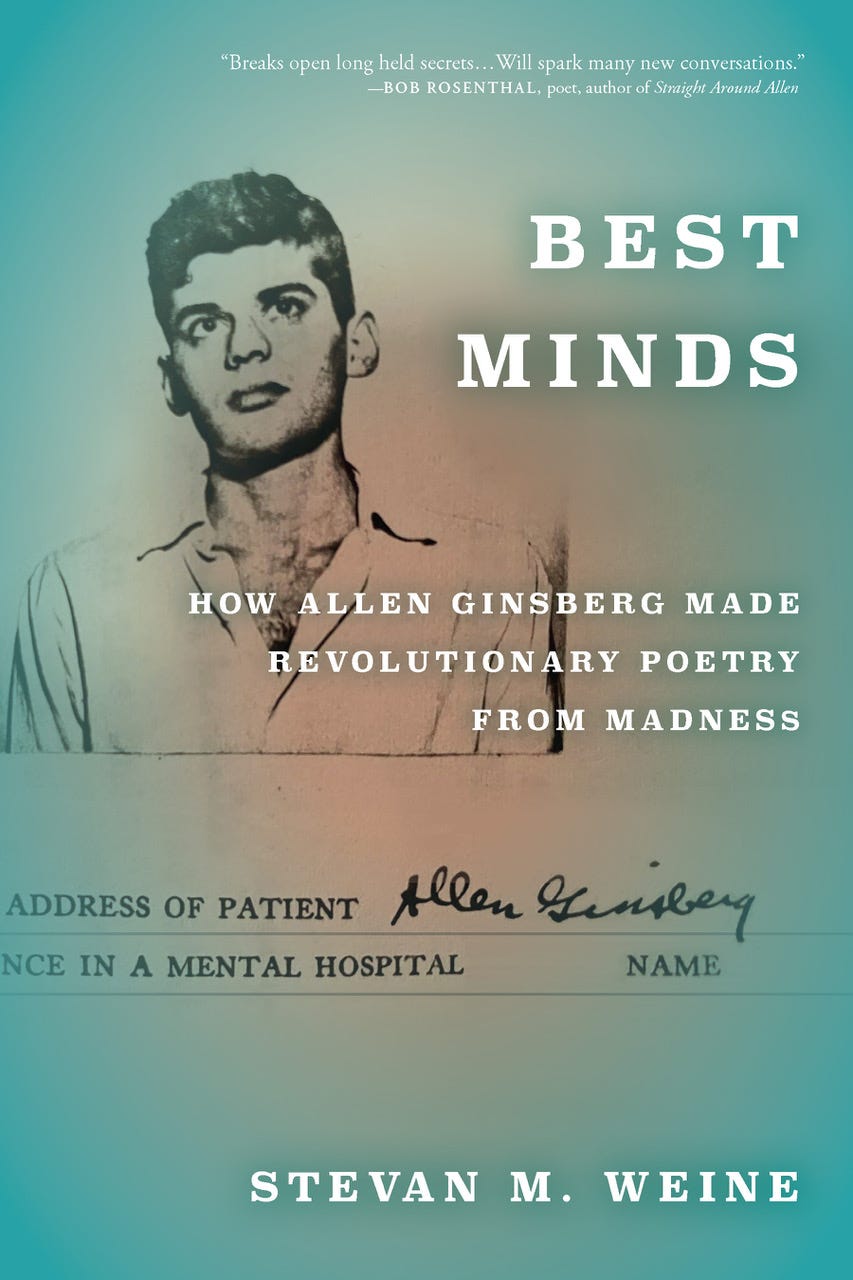

In his recently published book Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness, informed by a 40-year career studying and addressing trauma and writing about culture, Weine provides an exploration of the poet and his creative process especially in relation to madness.

As Weine explains: ‘Allen Ginsberg’s 1956 poem “Howl” opens with one of the most resonant phrases in modern poetry: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness”. My book offers a revelatory look at how poet Allen Ginsberg transformed experiences of mental illness and madness into some of the most powerful and widely read poems of the twentieth century.’

Pictured above: Author and psychiatrist Stevan Weine

Widely published – from the Chicago Tribune to USA Today and with prior books to his name – Weine says he is ‘very heartened’ at the pre-publicity the book has generated. Michael Schumacher, author of Dharma Lion, a well-regarded biography of the poet, wrote: ‘Allen Ginsberg's decision to allow doctors to lobotomize his mother was a devastating one that he spent a lifetime trying to understand.’

Schumacher adds: ‘Stevan Weine's unprecedented access to Allen and Naomi's psychiatric hospital records has provided a fresh understanding of the origins of "Howl" and "Kaddish" and illuminates the great distance that Allen travelled from his uncertain, troubled youth to the acclaimed poet the world came to know. Best Minds is a crucial advancement in Ginsberg and Beat studies.’

Weine’s research interests also extend beyond the Beats. He has also presented at conferences and published in academic journals on Ginsberg’s long-time friend Bob Dylan. This collision of concerns is serendipitous to Rock and the Beat Generation. We recently interviewed this leading psychiatrist about his book, about Ginsberg and Dylan, of course, but also about the ways in which rock music and concepts of madness have become entangled.

Our subject also delves in to some of the debates which enlivened our very pages in recent months, specifically the Jack Kerouac and bipolarity conversation prompted by Charles Shuttleworth’s book Desolation Peak, published late last year. We invite you to read this wide-ranging exchange…

Madness is a somewhat loaded and potentially dangerous word in the hands of the amateur analyst, Stevan. What in a succinct sense is madness? Does it have a use, a place, in creativity in the broader arts?

Madness is often equated with insanity or mental illness. But I see it as a much broader category which includes a wide range of phenomena including mental illness, but many other experiences such as ecstasy, visions, inspiration, liberation, deviancy, and more. The literary scholar W.J.T. Mitchell has even spoken of the need for a ‘Cultural and Symbolic Atlas of Madness’ akin to psychiatry’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

Allen Ginsberg has done a great deal to advance this concept of madness. In Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness, I discuss how Ginsberg’s poetry enlivened, explored, and elaborated a madness which for him was a disruptive and potentially redemptive life force. Through his poetry and countercultural leadership, Ginsberg offered himself as a witness to both the liberatory and destructive powers of madness.

Yes, madness can have a place in creativity. However, let’s avoid romantic notions which either equate madness with creativity or don’t adequately acknowledge the real suffering and loss which can come with some forms of madness. When Ginsberg wrote ‘I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness’, he was writing from the position of a witness to both breakthroughs and hardships.

Pictured above: Weine’s most recent publication

It’s helpful to look back to the Surrealists, who taught and inspired both Ginsberg and Dylan. At the Art Institute of Chicago I recently viewed Salvador Dali’s ‘Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and of the Rights of Man to His Own Madness’. Here Dali writes: 'When, in the course of human culture it becomes necessary for a people to destroy the intellectual bonds that unite them with the logical systems of the past, in order to create for themselves an original mythology […]'

The Surrealists found inspiration in the schizophreniform experience of the ‘stimmung' or 'truth taking stare'. This stare became a core strategy for breaking through the limitations of rational consciousness which shackled modern society. In the truth taking stare, the person sees reality in a heightened sense and mysterious unreality, as never before. They experience a powerful new way of seeing the world.

Ginsberg learned from the Surrealists, William Blake, and William James, and from his own difficult life experiences with his seriously mentally ill mother, and then devised his own innovative ways of engaging madness in his writing, especially his great poems ‘Howl’ and ‘Kaddish’.

As you will have seen, this website is particularly interested in overlaps and interactions between Beat writing and rock music. The questions below delve into both areas. This fascinating new book of yours plainly focuses on Ginsberg but you also have this Bob Dylan interest, so my gentle interrogation on both fronts should hopefully catch your attention!

You have given us so much to think about regarding the Beats and rock and roll in your books and website. Thank you for enlightening us about this relationship.

Those who are aware of Ginsberg’s story, know that, at age 22, he experienced visions and soon after was hospitalized at the New York State Psychiatric Institute for eight months. Until recently, not enough was known about what Ginsberg was struggling with, what led up to his hospitalization, and his experiences in psychiatric treatment.

In 1986, I reached out to Ginsberg when I was a medical student at Columbia University. I asked him for guidance regarding how literature and psychiatry looked at mental illness and madness, and he asked me for help in examining these aspects of his life history.

We knew the importance of not looking solely through psychiatry or literature, but both, and of being open to new insights and perspectives. Best Minds is the result of my research and it brings forth important new revelations about Ginsberg’s life and visions, his mother Naomi’s life and lobotomy, and new readings of some of his most important poems.

Regarding Ginsberg and Dylan, I recently presented a paper in Tulsa at the ‘World of Bob Dylan’ conference, entitled ‘My Generation Destroyed: Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg in Witness’. I sought to understand how Dylan drew from Ginsberg’s poems of madness, especially ‘Howl’ but also ‘America’ and ‘Kaddish’, and creatively reworked them in different directions so as to confront racism and violence in his protest songs. You can see how Dylan uses Ginsbergian language and adapts the position of the witness, which he got from ‘Howl’. This paper is being published in a special issue of the Dylan Review.

I was prompted by your investigations to consider the various signs of madness in the Beat circle (Ginsberg to Burroughs, 'Don't hide the madness'): Ginsberg and Carl Solomon and Naomi all in the asylum; Burroughs, Joan Vollmer and Kerouac all exhibited psychiatric issues. Did Neal Cassady, too, exhibit personality disorders? Burroughs, as a career addict, surely raises questions about his sanity in the conventional sense. The principles of the Beats’ ‘New Vision’ seem to frame in themselves a commitment to a madness of sorts…

Like several other notable 20th century artists and thinkers before him, Ginsberg derived inspiration and techniques from his encounters with mental illness and psychiatric treatment. Beginning in his childhood, he was exposed to his mother’s serious mental illness and damaging psychiatric treatments. As a young man, he faced his own mental health problems and in-patient psychiatric treatment with psychotherapy. He also had a close up view of madness and its mixed outcomes among his friends, such as Carl Solomon and many others.

In Best Minds, I tell the story of how Ginsberg not only avoided being crushed by these experiences, but turned them into remarkable art that inspired and uplifted many.

You can find the beginnings of this creative turn in Ginsberg’s writings on the ‘New Vision’, which grew out of dialogues at Columbia College with Lucien Carr and others about the role of the artist in society. In 1945, Ginsberg journaled: ‘The new vision lies in a highly conscious comprehension of universal motives and in a realistic acceptance of an unromantic universe of flat meaninglessness.’

Drawing from Rimbaud, Ginsberg believed the writer should take in the world as it is, ‘without ordered, rational preconception’, then, through writing, create an entirely new order and consciousness. It was largely up to Kerouac and Ginsberg, to write this new vision into reality. They welcomed crises which would disrupt the lifestyle and mentality of mainstream culture. For Ginsberg, giving consent for his mother’s lobotomy propelled him into a crisis which led to his 1948 Blake visions and eventually to new approaches to writing.

In my opinion, a psychiatric diagnostic approach to Ginsberg, to his Beat brothers and sisters, or to other artists, isn’t going to get us very far in terms of understanding who they were and the work they did as artists and intellectuals.

In the 2022 book Strangers to Ourselves, Rachel Aviv describes cases of people with ‘unsettled minds’ who don’t fit any existing diagnostic categories. Persons who also show remarkable co-existence of traumatic experiences, mental illness, brilliance, creativity, and resilience. That’s closer to how I think of Allen, not to mention Burroughs, Kerouac, and Corso. Biographers do not have to pigeon hole their subjects into an existing diagnosis. Instead, they should describe accurately what they find, preserving the nuance and complexity of co-existing vulnerabilities and strengths.

There has been a sparky debate at Rock and the Beat Generation about Kerouac's possible bipolarity. Charles Shuttleworth in his recent book suggested he might be exhibiting such symptoms during his stay on Desolation Peak in 1956.

In the essay introducing Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Peak, Charles Shuttleworth writes, ‘I’ve concluded that Jack did suffer from bipolar disorder, and I think anyone who reads the journal will agree, as he demonstrates virtually every symptom associated with the condition.’

As a psychiatrist, I don’t endorse making a diagnosis without actually interviewing the person. No matter how intimate and revealing the journals, it is not the same as meeting and talking with the person.

Making a diagnosis involves identifying symptoms, but it is more than checking them off a list. One must rule out other better explanations and pay attention to the chains of causality among the symptoms. You learn this through training and practice.

In my opinion, writers and critics should avoid directly diagnosing their subjects and have more important work to do. But if they have access to facts or opinions about symptoms or diagnosis, they can share them. They can cite evidence which they think speaks to the fit or lack of fit of a diagnosis, e.g. Jack’s symptoms of X, Y, and Z, appear consistent with bipolar disorder, but other characteristics do not.

They can also talk about their subject’s experiences or perceptions of the diagnosis or condition which a professional assigned to them, and the responses from friends, family, and helpers. Lastly, they can talk about the treatment their subject received or didn’t receive and its impact. They can also talk with an expert who can give them some guidance.

More than anything else, readers of Kerouac, or any other literary or musical work, want to know why does the presence of a psychiatric condition matter? Does it change our experience of their art? Regarding Kerouac, Shuttlesworth didn’t offer much along these lines, except for saying his decline began on Desolation Peak. It is left up to the reader to decide whether this matters at all.

My impression is that Shuttlesworth’s intentions were not bad, that his conclusion was an unforced error, and that we must all strive to do better.

Poet Jim Cohn has critiqued this interpretation at length in R&BG…

Although I find the acrimony tiresome and unhelpful, Jim Cohn’s letter is full of many significant insights about Kerouac.

I agree with his calling for a more comprehensive review of materials, and caution against drawing conclusions based upon very selective evidence.

I agree with his key insight that Kerouac’s journaling ‘is not solely the representation of his own personal mental health, but also serves as a representation of 1) his own artistic persona, 2) the writer’s own thinking about his semi-autobiographical-cast-as-fiction Duluoz Legend series’ organizational and aesthetic development as the Beat author envisioned it that summer, etc…’

I am also aligned with his formulation concerning ‘…the distinct possibility that Kerouac used mood swings, or came to use mood swings, as an aesthetic counter-narrative device throughout his bebop-influenced writing’.

I don’t know Jim Cohn personally. But it seems to me that he wants to protect Kerouac, and Kerouac studies, from psychiatric reductionism, even when it comes from a literary scholar purveying a ‘pseudo-diagnosis’. Further, he is trying to protect him from an unsubstantiated and undeveloped claim that Kerouac’s emotional problems while on Desolation Peak somehow explain his subsequent downfall. These are reasonable positions.

How can we do better in terms of understanding creative individuals like Kerouac and Ginsberg? I am in favor of promoting interdisciplinary inquiry, information sharing, dialogue, and collaboration, to unpack the complexity of these phenomena. In my experience, invitation works better than attack. Let’s invoke the spirit of Allen Ginsberg, who called upon poets, writers, and psychiatrists, to step up to higher levels of understanding, and more open and tolerant positions.

I'm sure you will know of Clinton Heylin, one of the significant historians of Bob Dylan. He also published a book in 2012 entitled All the Madmen: Barrett, Bowie, Drake, the Floyd, the Kinks, the Who and the Journey to the Dark Side of English Rock. It might be of interest.

I’ve read his Dylan writings, but not All the Madmen until you brought it to my attention. It's a group biography of six musical artists who ‘traveled to the end of sanity’: Pete Townshend, Ray Davies, Peter Green, Syd Barrett, Nick Drake, and David Bowie. Coincidentally, this book picks up in 1967 where Best Minds leaves off.

At the famous ‘Dialectics of Liberation Conference’ at London’s Roundhouse, organized by anti-psychiatrists R.D. Laing and David Cooper, Allen Ginsberg, Stokely Carmichael, Gregory Bateson and others spoke and explored the relationship between madness, politics, society, and art.

At the same time, a group of English singer-songwriters and their bands were themselves exploring similar territory. Heylin tells their stories and shares their art, which ‘signaled the start of an era when songs directly addressed the damage (being) done to eccentrics, and the end to a time when poking fun at them was a bloodless sport for English songwriters.’

The book’s hodgepodge of interviews, critical analysis, biographic study, cultural and intellectual study partially succeeds in presenting the challenges and achievements of this cultural moment. It gets frustratingly close to understandings that would need much more data and space to adequately explore, such as David Bowie’s relationship with his half-brother diagnosed with schizophrenia who suicided in 1985.

Again, one has the sense of being limited by selective evidence, partial understandings, and slogans more than theses which are rigorously examined. Madness is rendered as too much of a plaything for musicians and not appreciated enough as mental illness and public health problems requiring treatment and prevention.

The book ends on a somber note, where the anti-psychiatrists are forgotten, and the destruction wrought by madness seems to overshadow the artworks themselves, undermining the supposed link between madness and creativity which seems to animate much of the book, and not reaching conclusions which could help inform artists, practitioners, and scholars.

What about the so-called ‘27 Club’: Morrison, Joplin, Hendrix, Jones, Cobain, Winehouse – early tragedy, death; drink, drugs, excess (several with Beat allegiance). Are these behaviors a form of madness?

I read Howard Sounes’ book, another group biography of rock and rollers, this time of six highly talented and famous musicians who each died at age 27.

This is madness if we understand madness to be a big circle in which lies many different forms of experiences, including substance abuse, which is what really ties these cases together.

Substance abuse is itself a form of mental illness, characterized by dependence or addiction to alcohol or drugs, leading to physical, emotional, social, familial, and occupational problems and impairments. Different circumstances can lead to substance abuse, including family history, peer and cultural values and practices, exposure to adversity and trauma, and poor coping strategies. Substance abuse can also be associated with other co-occurring mental disorders or symptoms, such as Major Depression or psychosis.

Substance abuse is treatable. Yet one of the most striking themes among these musicians is that they did not get the treatment they needed to get better and save themselves from drugs and alcohol. The people around them either tolerated or encouraged their substance abuse, including doctors and mental health professionals. This is one kind of harm that rock gods and other VIP’s are especially vulnerable to.

There is a romance to these stories of self-destruction which is in some ways amplified in their retelling. For that reason, it is so important that we counter such narratives with accounts of rock and rollers and other artists who have gotten the support and guidance they needed from family and peers, from psychotherapy, and from alcohol and drug rehabilitation to face and manage their demons, and keep pursuing creative work. I just finished Lucinda Williams’ Don't Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You: A Memoir, which is one such powerful example.

Dylan, in the 1960s, was duplicitous, quixotic and mysterious, a kind of trickster who made up his biography. Was his falsehood a kind of madness?

In his press conferences with hapless journalists Dylan brilliantly performed madness, as in carrying a large lightbulb to a London press conference in 1965.

To me, this is more of an artistic provocation and effort to build a cultural legend. He is playfully disrupting the genre of the press conference which he found intolerable. People expected they were talking with either an entertainer or the spokesman of his generation who took himself way too seriously, and he let them know he was an artist with a ripe sense of humor.

His falsehood was not a kind of madness. Again, he is deliberately toying with the journalists’ and the establishment’s expectations of him in a performance.

Along those lines, I would like to point out that Dylan’s biography makes an interesting contrast with that of Ginsberg. In 1961, when Dylan visited Greystone Psychiatric Hospital in Morris Plains, New Jersey, which he renamed ‘Gravestone’, he came with his guitar to meet Woody Guthrie.

This cannot be compared to Ginsberg, who as a 9-year-old took the bus on weekends with his father to see his seriously mentally ill mother Naomi between damaging treatments of insulin, metrazol, and electroshock therapies.

Decades later, in 2004’s Chronicles, Volume 1, Dylan confessed that upon first arriving in Greenwich Village that same year, he ‘shucked everyone’ by replacing his placid Midwest upbringing with farcical hard knocks origin stories.

As far as we know, Dylan had an unremarkable middle class childhood with no known adverse or traumatic experiences of his own. Yet, as he later testified in ‘Blind Willie McTell’, Dylan absorbed the blues and all its adversity and suffering. He also absorbed Ginsberg’s madness and Ginsbergian language, but put it to different uses to protest war, racial disparities and injustice in his early songs. This is what I explore in the Dylan Review paper.

By the later 1960s and after, Dylan became a reclusive, asocial individual. Ginsberg, his great friend and almost father figure, was outgoing, personable, and gregarious. The two could hardly have had less similar personalities in the latter quarter of the century. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Why should Dylan and Ginsberg be similar? Just because they were friendly? Or because they have influenced one another artistically? I’m not seeing it. How or why is either one’s strategy inherently superior to the others?

Ginsberg had a genius for attentiveness and generosity, whereas Dylan despite his fame and never ending touring is intensely private. You don’t need to evoke madness to understand that. Who we think we are and how we carry ourselves in the world is driven by a great many factors, internal and external. It’s not for me to either diagnose or judge.

What is most important to me, and I imagine to most fans, is how they continued to do high quality creative work late in their lives and artistic careers. To me, that matters far more than the quality of their relationships, or the idea that they are a good friend or great guy (as long as they don’t deliberately hurt others). Each was following their own recipe for success and longevity.

Ginsberg made himself available to many, especially as a teacher. I was very fortunate to get to know one of my idols and to collaborate with him. No way I’ll ever meet the other, no matter how many concerts I may attend, or what I write. Yet I can still love Dylan’s art.

Thank you for your responses on all fronts. And it would be fun to meet some time…

For me, this interview has been a riot. I hope we can continue the conversation. Will I see you at the European Beat Studies Network gathering in Paris in September? Or, if not, do you have any favorite cafes or pubs in Leeds where we can meet up someday?

We’ll make something happen, I’m sure!

Note: Stevan Weine’s book Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness was published by Fordham University Press in the spring of this year

See also: ‘Weine, Ginsberg & madness: Raskin responds’, July 23rd, 2023; ‘Correspondence #21: Charles Shuttleworth’, February 17th, 2023; ‘Correspondence #20: Jim Cohn’, February 17th, 2023; ‘Book review #13: Desolation Peak, January 8th, 2023; ‘The legend of Zimmerman’, September 24th, 2021

A thoroughly engaging interview. I very much appreciate the robust and spacious concept of madness that Weine articulated, his encouragement of authors to avoid psychiatric reductionism and to explore the complexities of poets and authors' lives, and his call for collaboration across disciplines. It's rare these days to see such a fine case for nuance in interpretation, and it is most welcome. Your questions opened this dialogue marvelously.