Interview #15: Chris T-T

Established UK singer-songwriter and Beat follower who has retired his guitar for the pen articulates the tensions between poetry and lyrics as his complete song words is published

FOR CLOSE TO 20 years, the British songwriter Chris T-T was a fixture on the indie rock scene in the UK, frequently taking his own solo show on the road and creating a significant body of recorded work, playing with bands and collaborating with friends, adding his playing skills to other acts, including Tom Robinson and Frank Turner, and also performing further afield including at SXSW in Austin, Texas.

In 2017, this Brighton-based composer with a strong political twist and for whom words were an essential tool of expression, sometimes attack, decided to retire from the live circuit and the recording studio, leaving a musical legacy of more than ten albums and well over 2,000 stage appearances.

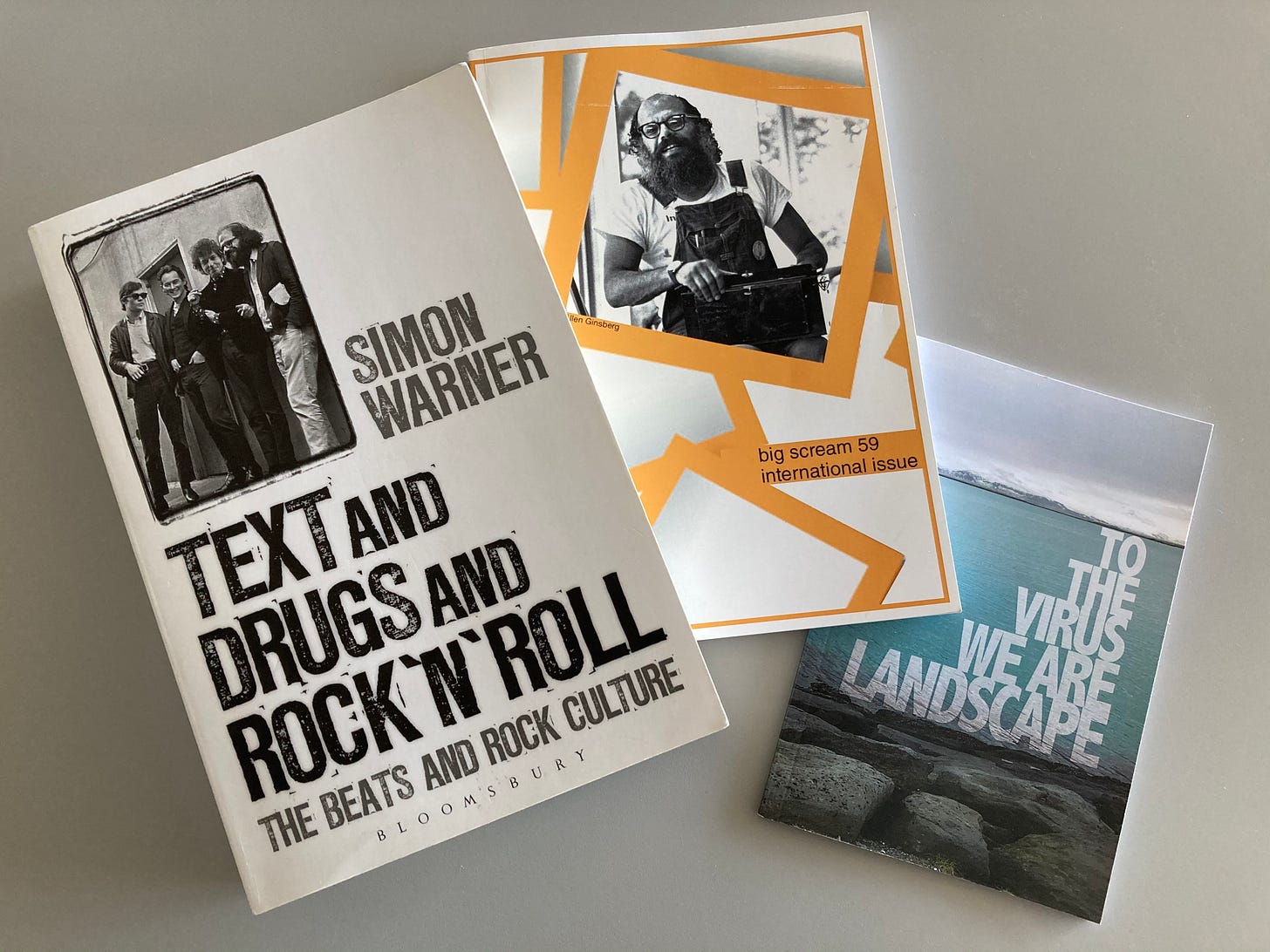

Compared by the critics to Blake and Neruda, he has, since stepping back, focused on journalism, broadcasting and poetry. His debut LP in 2001 was called Beatverse, a hardly-veiled reference – he has always admired Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti and Corso – and he shared his particular Beat inclinations in an interview in the book Text and Drugs and Rock’n’Roll in 2013.

His own poems, under the name CJ Thorpe-Tracey, have appeared in print in more recent times. Work was included in Ginsberg alumnus David Cope’s long-running journal Big Scream in 2020 and, in the same year, his verse collection To the Virus, We Are Landscape, a response in part to the pandemic, emerged.

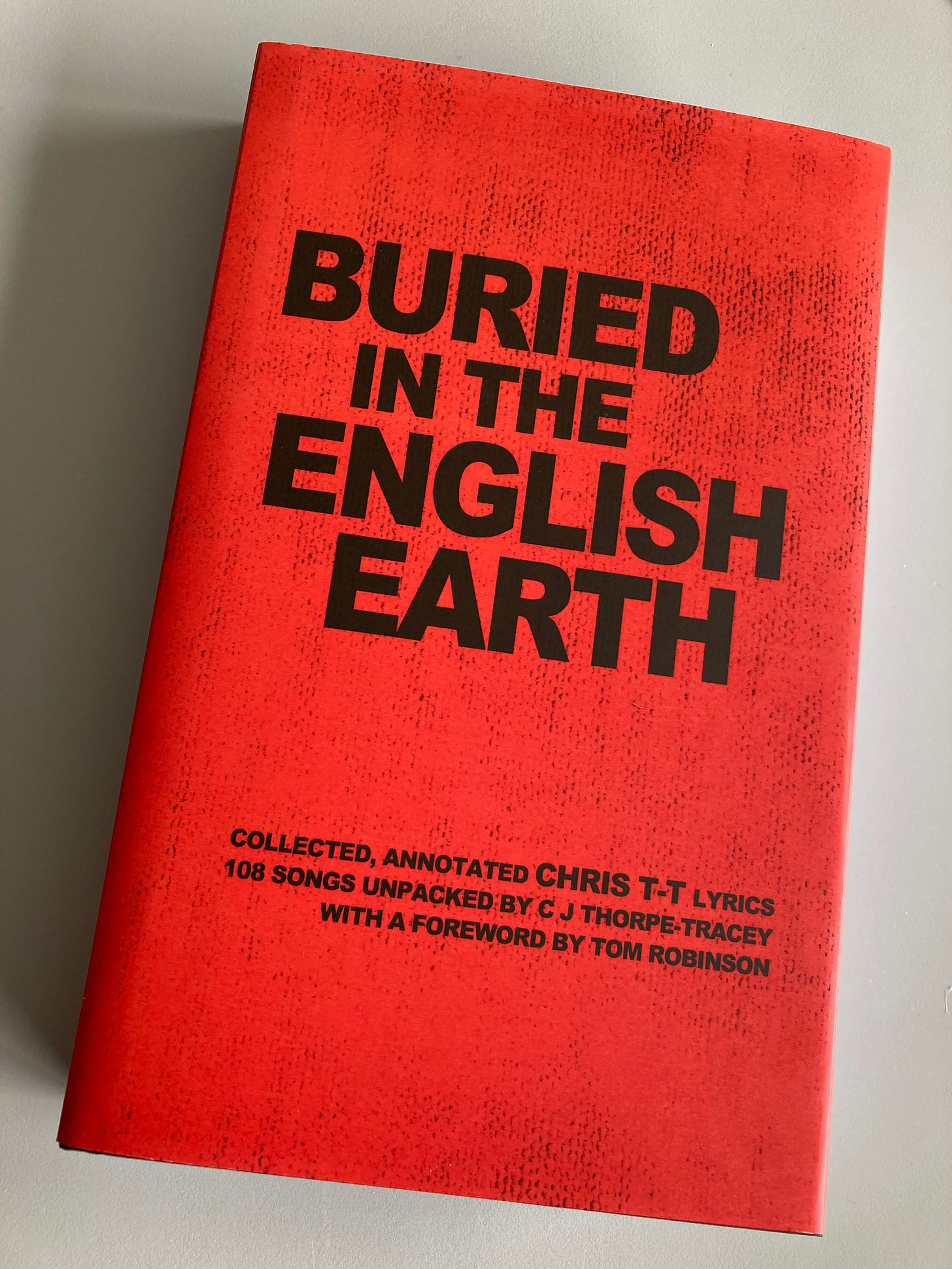

Now, the former singer’s pop life and lyrical voice come together in Buried in the English Earth, a handsome new volume providing a complete overview of his musical stanzas, rhymes and choruses, plus anecdotes and annotations, between hard covers.

Pictured above: Buried in the English Earth, just published

A previous contributor to these very webpages – he wrote about Ted Joans back in August – Rock and the Beat Generation has invited him to reflect on the overlap – or otherwise – between words in a song and words in a poem. Here are his thoughts…

What is a song lyric? What is it for?

Ha, I properly laughed at how huge a question this is, to start off with.

I think song is a fascinating, standout art-form, because it is comprised of two entirely different crafts, squished together, that is, a highly structured type of short-form music composition, plus an equally highly structured, formulaic kind of poetry.

With that in mind, I’d say that a song lyric is only half of a piece of art, both in intent and in outcome. The words do a bunch of different jobs, in collaboration with the music – convey emotions and tell stories, but with flourishes and nuances built upon the notion that they are being sung. Often (though not always) there’s the repeated memorable choruses and refrains to attract attention and hook the whole together.

So, intertwined with music composition, the song lyric is shaped around a pile of external factors.

What is a poem? What purpose does it serve?

By contrast, a poem is such a pure, solitary labour of written craft, punting for perfection. Writing a poem wrestles a piece of art – art that can stand alone and share truth, in and of itself – out of only language and human feelings and nothing else. The pen and paper and the will to finish the poem, that’s everything.

I think expressing the differences between the two in that context; in terms of the different stuff involved in songwriting and poetry-writing, is probably better than trying to dive into technical minutiae of form and rhyme and such. They’re real – but probably beyond me to articulate!

How do these formats differ from other kinds of writing or prose? I have often mused about the terms fiction and non-fiction. What do those terms mean when we discuss lyrics and poetry? Are they relevant?

I’m not sure ‘fiction’ or ‘non-fiction’ categories are relevant; to me poetry is an entirely different kind of creative act. So even if I’ve written a piece that tells a narrative story, contains non-real characters and plot-lines, if it is a poem, I don’t think of it as a ‘fiction’. The language and underlying meanings are more important. Also, in the wider publishing world, boundaries between ‘fiction’ and ‘creative non-fiction’ are blurring like mad anyway: we’re in the great era of traditional definitions and barriers being overturned and left behind.

Perhaps poetry has always been ahead of that curve. For me, the special bit that blurs the edges of genre and discipline is the live performance of spoken poetry – though that’s the furthest kind of poetry from my own.

Key early influences on my lyric-writing were the Beat poets, who I know you focus on and we’ve chatted about many times over the years, and secondly, early 1990s hip hop. Both Allen Ginsberg and Notorious BIG have the functional rhythm of verbal delivery, without the melody of music, so it’s a middle ground.

Rhythm and vocal performance are a great scaffolding for a poem’s assembly; so the words remain of paramount importance. They’re not superseded by music. Once melody gets into the mix, with the words sung instead of declaimed, the syllables are stretched or squished, all the verbal purity goes out the window, to foreground the singer’s skill in a different way.

Pictured above: Contributions to Text and Drugs and Rock’n’Roll and Big Scream plus a solo poetry collection

Which lyricists do you admire and why?

Impossible! Okay, I’ll just go off the top of my head for forty-five seconds.

Stephen Sondheim has been in my head because of his dying and the West Side Story reboot.

There are many shit lyrics in grime, but some of the better lyricists in that genre are incredible, Ghetts is outstanding, Wretch too.

Both the last two Little Simz albums have devastating, complex narratives. She’s in that grey area between rapping and performance poetry.

In terms of more conventional singer-songwriting, my favourite lyricist of the past five years has been Phoebe Bridgers. Her key influences, Elliott Smith and Conor Oberst (of Bright Eyes) have both written words I’ve adored in the past, folding poetic flourishes into excoriating self-analysis. For me, Bridgers shows signs of being better than both those men, if pop stardom doesn’t ruin her.

With Bridgers’ rise to quite mainstream stardom in the USA, she’s spearheading a revival for nuanced, emotively powerful lyricism within otherwise mainstream alt/pop/folk songwriting, mostly by women. So we get Lucy Dacus, and now, for example, the excellent young UK lyricist Holly Humberstone. In a sense, Phoebe Bridgers is even tangentially responsible for dragging Taylor Swift into the alt/folk world, which has been great for her songwriting.

I was a huge admirer of the Scottish indie musician Scott Hutchison, sadly no longer with us. He was songwriter and frontman of Frightened Rabbit. That was a band with beautiful musical awkwardness, which coalesced via his intense power of words into something intoxicating and affecting.

Is rock poetry an oxymoron?

The problem with the phrase ‘rock poetry’ is not the merging of ‘poetry’ ideas with a music form (that’s fine) or giving poems a musical soundtrack (also fine) but simply the outdatedness of that particular music form. Rock is dead!

In all seriousness, I’d argue that rock music (at least as we tend to understand it: song-based collaborative group music, played on guitar, bass and drums, mostly by white western men) is fundamentally finished as a mass audience art medium, certainly as a cultural or counter-cultural force. Its sounds, techniques and images have all been long appropriated by more contemporary genres and the kids are moving on.

Rock has remarkably quickly become just a peripheral, niche art-form, lost within the pop diaspora, similarly to what happened to jazz when rock’n’roll happened in the 1950s. That doesn’t mean rock music won’t still get made, nor even that great rock music won’t still emerge, occasionally. It’s just, it won’t have the same immersive mass cultural appeal.

When a rock band breaks through now, those artists swim alone in a pool of different musics, rather than as it was in the 1970s-1990s when many of the biggest artists in the world were rock bands, so they acted like they owned the swimming pool.

I suspect there’s a tendency among the more venerable schools of rock criticism to presume that the old fashioned rock songwriters were ‘the Great Lyricists’, while people working today in pop, R&B, hip hop and electronic music are not good lyricists. That is a wrongheaded prejudice and misses profoundly brilliant lyric-writing.

Young artists across all genres are writing sublime, complex, visionary words that leave conventional rock far behind in scope, nuance, turn-of-phrase, emotional excavation, basically every aspect of lyric writing.

There is a long tradition of poets working with musicians – from Ginsberg to Horovitz and Henri, Patti Smith and Linton Kwesi Johnson to Simon Armitage and Kae Tempest. Does this approach inspire you or otherwise?

I wonder if there’s two different kinds of exploration going on, which ought to be differentiated: first, poets whose already completed works are set to music (as if they’ve been given a soundtrack, to be performed alongside musicians) and secondly, poets attempting to write songs instead of poetry. Like the Beats and hip hop, Kae Tempest’s words are rhythmic and sit on a blurred line between hip hop and spoken verse. So they lend themselves to musical accompaniment.

I do think some of the artists and works of art you mention inspire me greatly. I guess any kind of cross-cultural collaboration or exploration is interesting. A decade ago, I had a go myself, setting a bunch of A.A. Milne’s children’s poems to music for a solo show on Edinburgh Fringe.

Obviously, Milne was easy to collaborate with, because he was dead. It was one of the most rewarding things I did. That said, those poems were easy to turn into songs because in some senses they already were songs. Milne wrote chiming, repetitive rhythms and cadences to suit a sing-song repetition by children. It was like traditional folk song, more than modern poetry.

I love guitar-based rock music where the lyrics are proclaimed, instead of being formally sung. Right now, in a small way, there’s something of a resurgence of that style, led by acts like Sleaford Mods, the Hold Steady, Courtney Barnett, with a newer burst of UK bands following those lines, such as Idles, Fontaines DC, Pigsx7, Shame and Yard Act. Spoken words without melody can be rapped, or shouted, or screamed. Which makes them very flexible across genres.

Could you see some of your song words standing alone as verse?

I’d say only a tiny handful of my song lyrics might work as standalone poems. Off the top of my head, just three or four (out of 108 songs) where the lyrics may – just about! –have that self-contained quality, the sense of ‘wholeness’, of being unencumbered by the formality of music.

More generally, on the whole I’d say no, because in the writing of the lyrics I was knowingly doing that half a job I mentioned earlier – and I placed a lot of the emotive and creative weight onto other parts of the process; the singing, musicianship and production.

You have written, recorded and played in different modes, as solo artist and bandleader: your styles span thoughtful introspection, political proselytising, rock music fuelled by energy and driven by noise. How do these varying platforms change the lyrical elements in your composition?

Funnily enough, I think it was mostly the other way around for me. The varying platforms didn’t impact the lyrical elements, so much as they were chosen and finessed to support the lyrical elements, which had been created first and were more fixed. It’s all a matter of degrees, of course.

Sondheim famously said ‘content dictates form’. So usually my explorations of varying music styles and arrangements didn’t tend to impact lyrics. What was happening — for me at least — was the shape of the lyric and its style would determine how the music came together. If I did decide in advance on a particular style of a record, it was more a case of picking which (already in progress) songs might work best in that style.

Could the poems you have been writing in recent times (or maybe longer than that) be set to music with suitable effect?

I’m still new to writing poetry and on a steep learning curve. Though it was the Beats who inspired me to write songs in the first place, with their potent declamatory stuff, my own poetry is primarily of the page, not spoken.

In some ways it is (deliberately) quite small-c conservative, conventional poetry, especially while I’m still learning. It’s not meant to be in any way declamatory or performed. I haven’t done any poetry readings.

Having spent decades performing and utilising my honed stage-craft to ‘sell’ my music to an audience, I’m honestly not interested at all in doing that for poetry. I’ve not gone to any poetry open mics or anything like that; they don’t interest me. And to be fair, nobody’s expressed any interest in me doing that either, so it’s golden.

It’s the words on the page that interest me. So I think (and hope) that the poems I write now would be tricky to set to music. I’m steering clear of formal rhyming and rhythmic structures. I’m trying not to write anything that sits in an even format, let alone formal ballads.

Sometimes I think that the current vogue for spoken word over an uplifting musical background is more about capturing one particular kind of – phoney – emotional hue, rather than expressing something truthful. It’s about conveying a bland sense of possibility and aspiration to the listener, teasing them with some vague possibility of empowerment, exactly like they do in advertisements (and they use this same kind of spoken word performance in adverts!) without actually giving the listener the recipe, or being specific enough, to attach real meaning.

What are the creative problems posed by these binary components of lyric and verse – or perhaps you see them as complementary forms rather than in opposition…

For me – in the moment of experiencing doing it – it feels as different as painting and dancing. There’s never been a moment, not once, where I’m writing something and unsure whether it’s a poem or a song. So I don’t think there are creative problems at all.

With all kinds of writing except poetry, I have an idea and note it down, then over a few weeks, I sketch it out further and once it’s more than a paragraph, I’ll know what it is, whether it’s a short essay or story, or a song, or a script, or just a tweet, or whatever. The form emerges from the idea.

The exception to that is poetry, because it’s not ideas but phrases and words themselves that drive my poetry. A phrase or single line or couplet will appear and I’ll write it down in the Notes app on my smartphone.

Okay, so that means my verse sits specifically separate to all my other forms of creative writing. I hadn’t thought about that until now.

Since quitting music in 2017, I’ve written six or seven potentially good songs. They showed up and I’m not refusing them, even though they don’t have a public outlet anymore. I write them to completion, make them as good as I can, then put them in a box. Well, a hard-drive, but you get my point. And there has never been a moment when I’ve wondered it they were in fact a poem. It’s never felt remotely connected.

After more than two decades identifying as a songwriter and a live performer you decided to cast off that skin and become something else. What have you become?

I think I’ve become a writer. With the caveat that honestly I haven’t yet had enough work published or enough external reaction to justify the label. But that’s what I’m doing with my time.

Through 2022, I'll try to finish a couple of larger works that I’ve been plugging away at, and sell them to agents or publishers. If that works out, I’ll have more confidence to own the sacred label ‘writer’.

In Spring 2021, I won a DYCP grant from ACE (Arts Council England) to develop my writing career. That grant specifically doesn’t require me to deliver any actual written work, it’s about developing the business and networking side of a writing career.

I feel that I’ve done well this year, building good contacts and relationships in different corners of the publishing industry. But then of course, the proof of the pudding is, will I actually manage to sell some long-form written work, once it’s completed?

A more personal, troubling answer might be: though it’s been more than four years, I haven’t yet dealt with the psychological and emotional fallout from being a songwriter and music artist my whole adult life, and then turning my back on it. I suspect it did deeper damage than I felt in the first few months of 2018, after I quit. I felt liberated and bereft at the same time and I still do.

Songwriting is precarious; poetry more so. Terms like career are barely appropriate to those fields of activity in an increasingly digitised and uncertain artistic environment: the consumer assumes that music and writing will be 'free'. How does a creative individual function in the third decade of the 21st-century? Are there freedoms and opportunities or just restrictions and stifled ambitions?

Sadly, in horrible feudal late stage capitalism as we are, the primary way a creative person can function is to compromise and commodify our creative spirit, often at the most profound level, in order to make rent. Perhaps the least damaging compromise is to teach. Otherwise, we sell commercial products and services, for clients who pay us.

Ultimately, most creative people who aren’t teaching are in advertising or marketing of some kind. If we do well sucking up to the man, we’re rewarded with some time to work on our heart-driven projects on the side.

The threshold of success required to become a true creative professional has gone up and up. I think I was very lucky indeed that I got going as a musician in the CD era and began to make a name for myself before the great changes. I was also quite savvy to the internet-driven paradigm shift as it arrived.

I was still making a modest but decent income and paying my mortgage right up to 2016, 2017, when I gave up music. But I did notice, the moment I tried something different, client-based work, my income went up fast. Within 18 months of quitting music, my income had basically doubled – and I was hardly doing anything, compared with touring 150 days a year.

About two years before I gave up being Chris T-T as a job, I decided to roll back the number of shows I did each year, so I could be at home more. As a back-up I launched a micro-business producing radio and editing podcasts. Within nine months my day-rate went up above my gig fee.

The 'middle class’ of career success in the arts is decimated. Now the arts are filled with people either making no money, doing absolutely anything they can, such is their desperation to ‘break through’ to success, or who don’t need the money because its already in their family. Or, a very tiny handful of very successful artists who’ve made their fortune – and it’s that unlikely subset of people who are held up as the example of achievement for everyone else.

I wanted to be a professional genre artist. When I started out, that was hard work but straightforward. Now it is incredibly rare, across every kind of creative trade. Today, I still earn most of my income producing and editing spoken audio content (radio and podcasts), which is good because I enjoy it and it doesn’t take much time.

You have published some poems in the US; you have also issued a solo collection of your poetic writing. Do these achievements give you impetus to move forward?

They do, very much. But I suspect at first they gave me a false sense of the poetry scene’s pace. I made quite a healthy profit selling my first pamphlet, and later heard from other poets who are much better known than me, technically more successful than me in the poetry world, that actually I’d made a more money than they usually did for a pamphlet. Thing is, I wasn’t selling to poetry readers, mostly I was selling to people who already like me anyway, so decided to try my poems.

I hadn’t realised quite how tiny and insular the poetry scene is. And perhaps they might resent it a bit, especially if they’ve published a multitude of things and people have heard of them and they’ve been doing it ten years – but they still only sell 200 pamphlets each time.

I learnt: the poetry audience is small, the poetry establishment is exploitative and entrenched, and the tangible rewards for work are minuscule. But I really, really love trying to write poems.

So, I probably published that first pamphlet too soon and instead should’ve sent individual poems off to magazines or competitions first, maybe for a few years even, before self-publishing. It’s a punishing level of humility and ‘apprenticeship' that I’m not used to, coming out of the music world!

You’ve have also talked to me about publishing a large body of lyrics you have penned over many years. What is the motivation and meaning behind that project? Do you plan to explain and annotate or will the words to the songs stand alone in that planned collection?

I’m pleased to say I've finished this book, and has just been published. It’s called Buried in the English Earth and contains all of my 108 commercially released songs. The annotation is a blend of explanations, etymologies of words and phrases, and sources of inspiration.

I’ve included a few stories of practical songwriting and recording but I’ve steered clear of tour anecdotes – I didn’t want a memoir to sneak in the back door.

Note: CJ Thorpe-Tracey has his own newsletter The Border Crossing. His article ‘Ted talk: Keeping up with Joans’ appeared in R&BG on August 13th, 2022.