Interview #16: Ramzy Alwakeel

A Music graduate who focused on the politics of pop, its subcultures and resistance, not to mention the Beat Generation, now has two praised band biographies on his journalistic CV

FOR CLOSE to 20 years I taught classes on popular music and politics, subcultures and, indeed, the literary voices who formed the Beat Generation. The intersection of styles from jazz to folk, rock to rap, with arguments of the day provided multiple ideas about cultural resistance, protest and activism, social change and the power of art to influence and challenge, even alter, attitudes to critical topics such as race, sexuality and identity.

Ramzy Alwakeel, today a successful investigative journalist in London in the capital’s active weekly press, was one of those students who took those courses in the Leeds University School of Music, all the time working frenetically as a would-be music critic on the campus’ student newspaper.

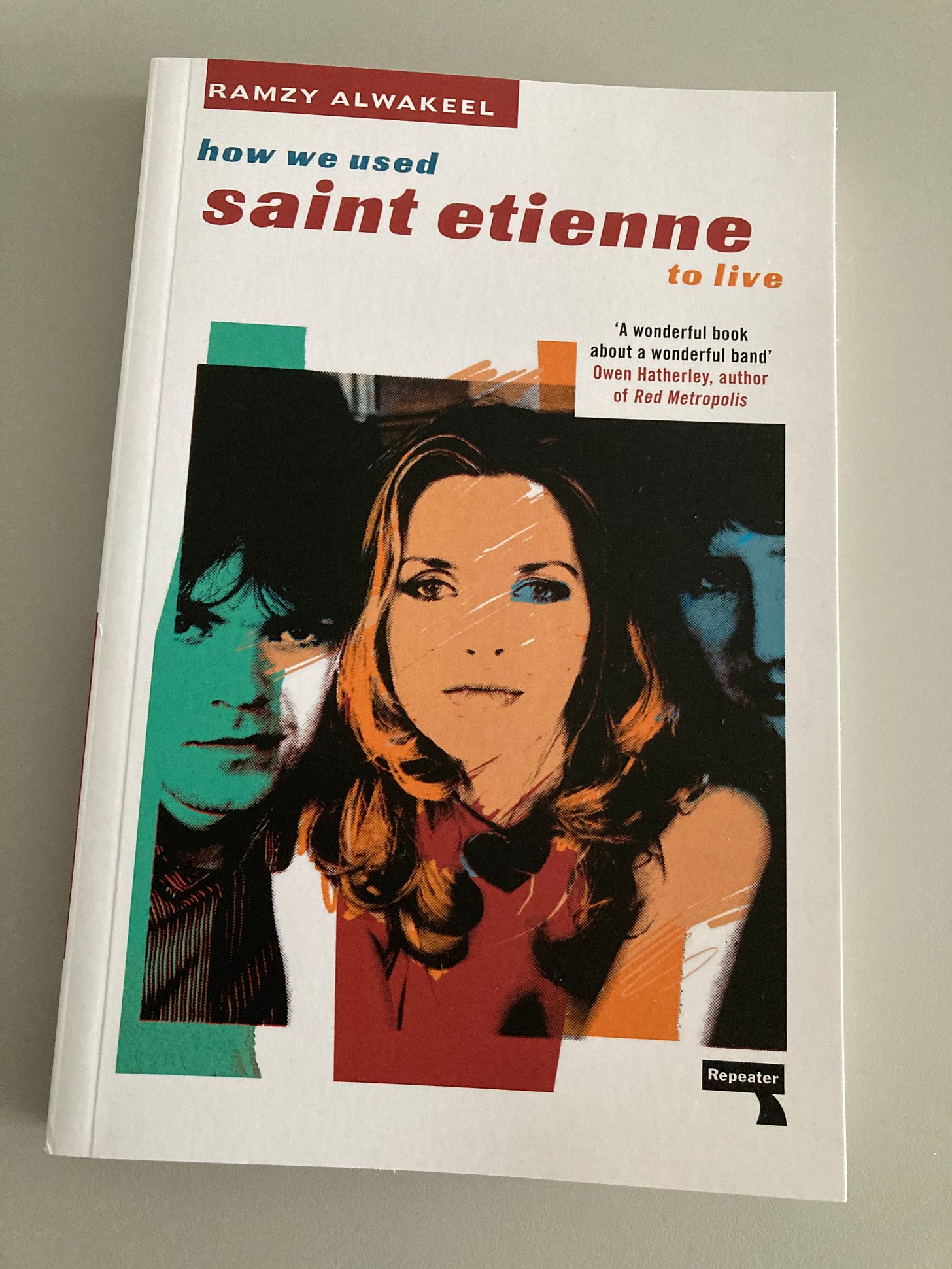

Pictured above: Ramsay Alwakeel’s most recent pop biography

More than a decade on, Alwakeel has just published his second pop biography, a history of UK indie favourites Saint Etienne to follow his debut volume on the Pet Shop Boys in 2016. Long out of the academy but still as intellectually engaged and politically conscious, I was interested to hear how his degree studies might have shaped his attitudes and particularly his various present projects. I interviewed him as 2022 ticked to a close…

You explored the relationship between the Beat Generation writers and popular music as part of your degree. Did the connections that were investigated give you an understanding of or insight into notions of subculture and resistance and do they have any relevance in the post-millennial world?

I have a slight confession which is that I never really felt like the Beats and the music that they influenced were ‘for’ me – which is perhaps more to do with the way their work is used as a cultural signifier than necessarily by any of the writing or music itself (even though I do love some of the musicians who drew from the work of Beat writers, particularly when it came to someone like Burroughs and his chaotic methods and influence).

The way Beat writers and 1960s musicians are hallowed, I suppose, triggers my hatred of the fetish for ‘authenticity’ that typically seems to me to be more about form than content, even when that form is itself mass-produced and aestheticised, and to have overtones that are problematic and tend to exclude art created by different groups of people.

The culmination of which is something like the ‘Disco Demolition Night’, which it’s hard not to see as being driven at least in part by racist, sexist and homophobic instincts about what counted as ‘real’ music and the feeling that music used by queer and black communities was somehow ‘replacing’ the music used by straight white men. None of this, of course, is Bob Dylan’s fault!

The reading list for another of the modules you taught, on pop music, politics and protest, directed me to the work of academics like Steve Redhead who kind of dismantled the idea that subculture was real. I don’t know whether he’s entirely correct, but I suppose I’m quite sceptical of the idea that communities of artists, musicians and writers simply being angry about things can change much in itself because they don’t wield much economic power – and there is, as I said above, a certain aestheticisation of protest movements that you get through the way the Beat Generation’s work is now used and referenced as this kind of golden era of protest, that I don’t think is particularly helpful.

But equally it might just be that I don’t really ‘get’ their work because of my own positioning, and that it did what it needed to do at the time. I do, though, think that benchmarking a particular generation of largely white American men as how protest or subculture are supposed to look and function isn’t, in my view, that useful and means we’re likely to miss, or misunderstand, acts of resistance happening today because we’re looking for the wrong things. I suppose, though, if I’m being blunt, I don’t know that music or creative writing have that much to do with resisting immigration raids or destroying fossil fuel infrastructure.

You studied music at university, but to what extent is music merely a cultural expression and to what degree does it have the potential for political influence?

Undoubtedly music has been used to raise spirits and to organise people and to name and explore shared trauma and to reinforce communities that have gone on to achieve political change as a matter of life and death in different parts of the world throughout history, but all that I suppose I’m qualified to talk about is the limited amount of western late twentieth-century and early twenty-first century music that I’ve studied and listened through my life.

There’s a line in the first chapter of my new Saint Etienne book that says the ills of the world can’t be fixed using popular music, but that popular music might at least be the soundtrack to praxis. What I suppose I mean is that I believe it is politically useful, and perhaps even a political act in itself, for music to bring together people with common interests, and to fire those people up, either simply by placing them in safe and common spaces where passions run high and organisation might happen, or by communicating certain things to them, through lyrics, and through the way that music is positioned in relation to power.

For instance, I explore a little in the book (and I believe I wrote an essay for you on this subject while I was at Leeds) about legal and illegal sampling in the 1980s and 1990s and how they drew attention to copyright and the extraction of value by the record industry, and about the proscription of certain kinds of socialising like the Criminal Justice Act that tried clumsily to illegalise rave parties and almost inadvertently politicised an otherwise arguably apolitical scene.

On a more materialist level it’s hard to know how much pop music is a genuine potential force for change, versus how much it is some sort of opiate, a way for politics to be aestheticised and sold back to people by the same structures that oppress them, so that they let off steam and then go back to work. I guess both things can be true at once. But it’s certainly the case that we haven’t yet brought down capitalism, using pop music or indeed anything else.

I learnt a lot about, and was indeed quite fired up about, struggles in recent history over workers’ rights, housing inequality and queer liberation thanks to the pop music I listened to when I was growing up, and still do. I now have a job that relates directly to shining a light and campaigning on those things. But the true effect of that – how much I would have been interested in those issues anyway, and how much journalism is even a real tool for change – is hard to assess.

You are a news and investigative journalist today yet you write about what we might regard as classic pop music. How do acts like the Pet Shop Boys and Saint Etienne express a form of politics through their accessible and amenable output? And how do you align your professional pursuits with creative material that might be regarded as ephemeral and superficial? In other words, I guess, what is pop music for?

This taps into the age-old pop v. rock argument that I touch on above, where pop is supposedly artificial and rock is authentic. Suffice to say, I don’t have much patience for the idea (which I know you aren’t endorsing here) that a band like the Pet Shop Boys are ephemeral or superficial just because they sound a certain way that draws more from queer and black musical traditions, that is electronic dance music, than from the legacy of white men with beards and acoustic guitars, deliberately making records that sound ‘lo-fi’.

Pictured above: A debut volume focusing on the Pet ShopBoys

There is some alignment between the two halves of my career in the subject matter that the Pet Shop Boys and Saint Etienne have directed me to. In both my books I’ve written quite a lot about housing in London, which is an interest that I first developed because of songs like ‘The Theatre’ and ‘King’s Cross’ by the Pet Shop Boys when I was very young, and gradually as I read more about what had influenced these songs I loved, I learnt more about what would eventually become a professional pursuit.

Similarly, I learnt about AIDS and the British government’s homophobia in dealing with it through reading around Pet Shop Boys songs, and my first introduction to queer subculture was probably through seeing their musical Closer to Heaven when I was 13, which isn’t exactly the most subtle piece of theatre ever created but was the first time I saw anything like a gay club represented in popular culture.

Two of the areas that I have specialised in as a journalist are housing inequality and LGBTQ rights, so, in that sense, I think there’s very likely to be a connection (though, obviously, I’m very, very gay so it’s not like I could really have avoided learning about these things at some point, and similarly I worked at local newspapers for years where I learnt about how terrible some of the conditions in British social housing were, how inadequate its supply was and the reasons for that, and so on).

The same, to be brief, is true of some of the things about Saint Etienne’s work that interests me. In short, I think it’s more about areas of interest than it is about whether or not something can be considered protest music, or political, in a conventional sense.

Artists who tapped into the Beat reservoir are many and varied, influential and significant – Dylan and the Beatles, David Bowie, Steely Dan and Patti Smith, Tom Waits and Sonic Youth. Was this a cultish trend which hardly survived the century or is the notion of the literate – and literary – songwriter still alive today?

I think the fact that Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 is all that really needs to be said here. Whether or not musicians are still drawing from the same writers that Bowie, Dylan, Smith and so on drew from isn’t a question I can really answer, but rap and hip hop are obviously incredibly literary genres.

You have someone like Akala who is both a musician and a writer, and there are musicians whose lyrics are often or always spoken word (even if they aren’t what you’d call rap) influenced by those genres and others that have been successful at different levels – Kae Tempest, Self-Esteem, Real Lies. I don’t really know what it would mean for a songwriter not to be literate and literary, to be honest.

I don’t think lyrics have got worse, or less literate, in the last 60 years. But again, it’s all about which literature and literary techniques and music you consider to be ‘authentic’, isn’t it, and that is a problematic premise.

When you are an undergraduate, although I knew you were writing and editing for Leeds Student, I didn’t really talk about your professional aspirations. I’m assuming journalism was your principal area of ambition after you left your studies based on your extracurricular activities while on campus.

I left university with no clue about what I was going to do, actually. Most of the career options for someone with a Music degree were things like being the in-house composer for an advertising agency and I knew I didn’t want to do anything like that.

I’d wanted to be a music journalist as soon as I got to university and started working at the student paper – I absolutely loved that world, as much for the feeling of being an insider as for the excuse to listen to records and go to gigs all the time – but I knew by the time I graduated that this wasn’t really something people got paid to do unless they were extremely lucky.

So I left uni, moved to Manchester, worked in an office for the NHS and got quite depressed. It wasn’t until a meet-up with all the old Leeds Student alumni at an awards do a few months later that it clicked I wanted to go back to that world in whatever capacity, which is why I applied to do a journalism postgrad.

I thought that perhaps I would end up writing about music after all, but these courses railroad you into local press and before I knew it I was a reporter in Romford covering crime and court cases and community fetes and political rows and potholes. And to my immense surprise, I absolutely loved it. But honestly I never saw myself as a writer. I didn’t even study English at A-Level. If you read the books I’ve written, I’m sure they’re terrible from any kind of technical perspective!

Thank you, Ramzy, for sharing these enlightening and enlivening ideas…

Note: Ramsay Alwakeel’s latest book How We Used Saint Etienne to Live has just been published by London’s Repeater Books. His first title Smile If You Dare: Politics and Pointy Hats with the Pet Shop Boys was published by the same outlet in 2016