Interview #31: Jeff Young

Twin cities host Beat-like adventures

JEFF YOUNG is a Liverpool-based writer who has contributed work to the theatre, radio and television. He has penned broadcast essays for BBC Radio 3 and collaborated with artists and musicians on sound and installation performances. Until recently he was Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at the Screen School of Liverpool John Moores University.

We review his latest book Wild Twin, a riveting feral adventure published last year, elsewhere in the pages of Rock and the Beat Generation. Here we interview Young about his inspirations, including the Beats, and his lifelong passion for popular music, all evidenced in a vibrant and revelatory memoir he subtitles ‘Dream maps of a lost soul & drifter’…

Simon Warner: Your book Wild Twin has multiple literary and musical references. What relationship do you see between novels and poetry and popular music? What alchemy occurs at this intersection of words and sound? It's a topic of particular fascination to me as this R&BG website explores that terrain where music inspires literature and fiction feeds into rock and other such styles.

Jeff Young: I’m not sure I particularly categorise the different forms. In my own work I’ve tended to drift across the fields – writing for theatre, memoir, stories, essays, poetry and performing in collaborative groups with musicians and visual artists. In some ways I see Wild Twin as a series of prose poems. It’s not a linear narrative, it has passages of stream of consciousness, uses dissonance as a device, breaks up the temporal flow of the narrative with flashbacks and asides to the reader and so on.

There are references to music throughout – someone compiled a Spotify Playlist of music referenced in the book and it’s over twelve hours long! A musician friend has composed short soundscapes for passages from the book using my voice in a spoken word collaboration. There are a lot of literary references in the book – particular inspirations, books used as guides to certain places, poems quoted in search of insights into certain emotional states.

If the book had an index, it would be long and full of the names of musicians, writers and artists. I use music as a stimulus to write. It’s a crucial part of the process. Certain types of music will conjure certain moods – Miles Davis or Thelonious Monk gets me into one atmosphere, Captain Beefheart gets me somewhere else. I have written sections of the book listening to Pere Ubu or John Cale and other sections listening to glam rock. The book is saturated in sonic atmospheres.

It's just the way my mind works – a constant flow and churn of books, architecture, songs, films, paintings. I don’t have an ordered imagination and I think I nurture creative chaos. My hunger, appetite and thirst for culture feeds into the writing and I’m trying to evoke the potency of that on the page. I guess this where the alchemy lies – in the potency of the spell conjured by the multiple sounds and visions of culture.

SW: Your adventures were determinedly unbound and you struggled at times with your picaresque life and toiled for your art. To what extent were the Beats your touchstone?

JY: The Beats were a huge touchstone. The Beats and their precursors and those who came after. Because I read a lot of Beat and countercultural literature in my teenage years, they were an inevitable part of my thinking. One of the main impulses for my journey to Paris was the Beat Hotel because I’d read Corso, Ginsberg and Burroughs and was fascinated by the hotel and the creative inferno the took place there.

I’ve always been fascinated by ‘scenes’ - Left Bank Paris, Greenwich Village, Soho and so on – and my interest in Parisian ex-pat culture, Americans in Paris, jazz musicians in Paris, people like Trocchi, all this created in my mind an imaginary Paris. I’d never even been abroad when I went there but I’d invented my own Paris from books and films and paintings.

I don’t think it’s a particularly good book but Kerouac’s Satori in Paris would have been one of the inspirations for my journey. Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer was another inspiration. It’s a problematic book in many ways, particularly the way he writes about women, but there’s such a vivacious lust for life in its pages that – despite the squalor – made me think of Paris as THE place for me to be. And of course, Miller is a forerunner of the Beats, so it fits.

The struggles in the pages of these books, the struggles and deprivations the various writers went through seemed to me at the time to be part of the adventure. Poverty and bedbugs were part of the romance! So, the Beats were inspirations for the journey and to a degree for the writing, although I draft and redraft carefully so what I do isn’t ‘first thought, best thought’ at all, it’s much more considered and shaped.

Yes, the Beats were certainly a touchstone for the wanderings, less a touchstone for the writing although there is a Kerouacian atmosphere to stretches of the book. People who you might describe as ‘Beat adjacent’ such as Kenneth Patchen and Kenneth White are influences on the writing too. The Journal of Albion Moonlight and Travels in the Drifting Dawn are shadow presences in the pages of Wild Twin.

Pictured above: Jeff Young

SW: Your European odysseys fed you valuable material and fuelled your original voice. How do you feel now about those somewhat restless escapes: all worthwhile or any regrets?

JY: Someone asked me a similar question at a recent book event and after a few moments of thought I answered that I’d do it all again but this time I’d wear warmer clothes. I don’t think of wrong turnings as mistakes – they’re part of the accumulating story. I made some naïve and ridiculous wrong turnings and go into some terrible and dangerous situations, but they make such good stories that it would diminish the life lived if you could somehow correct them.

I’ve always been someone who goes down the alley you’ve been warned not to go down. I want to see what’s down the alley. Of course, now that I’m older and have numerous health problems, I live a very careful and quiet life and as my partner tells me I’m frightened of change. In those days I was all about the change and the restless search for the wildness. Now I go to bed at 9pm and seldom leave the house.

SW: The voice you express in the pages of Wild Twin is frequently fragmented and impressionistic, wayward and promiscuous, in the trails it pursues. Did a version of Kerouac sketching feed into your process?

JY: Yes, so sketching is the main event. Ever since I started writing properly in 1985, I’ve kept pocket notebooks in which I scribble thoughts, phrases, things overheard, drawings, lists of books and records to look out for and so on. As time moved on the notebooks became more elaborate – more consciously artistic – and they have been a crucial part of my creative process for 40 years.

To a degree, I like the books to have at least a suggestion of this – the voice changes, the style evolves and mutates, the tone varies. I’m not interested in consistent tone; I like to shake things up. Kerouac’s Visions of Cody is a talismanic book for me and I think that much of his best writing is in its pages.

In the 1970s, it was quite hard to find Beat literature in Liverpool but there was a great shop called Atticus which was like Liverpool’s answer to City Lights. (In fact WSB visited the shop at one point and gave a book reading and signing) I bought most of my ‘Beat Library’ there, and this played a big part in forming my attitude to life and art, to my restless desire to travel, to my restless imagination.

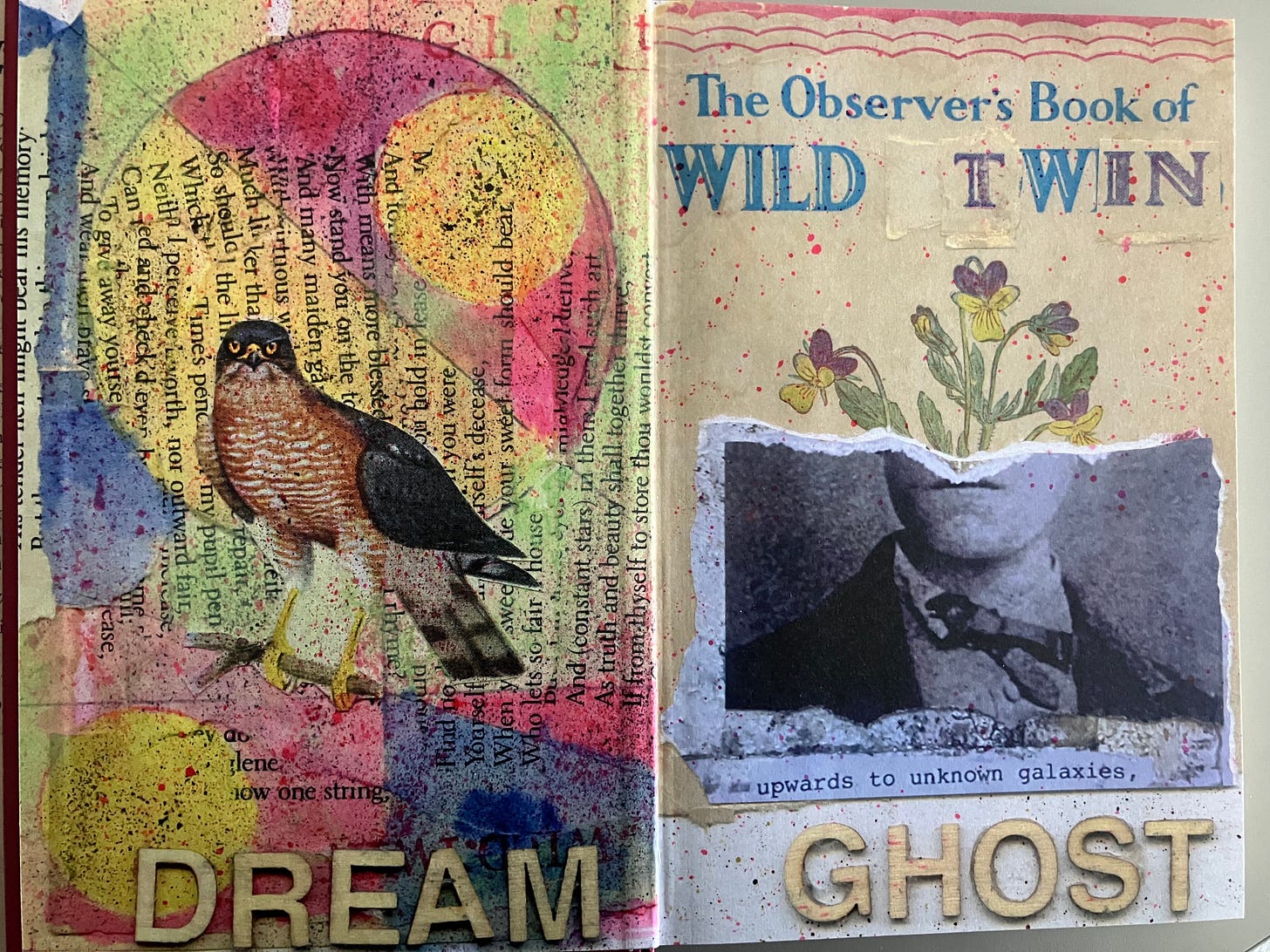

Pictured above: Wild Twin endpaper, a collage by the author

I have to say that some of Kerouac’s writing about his journeys is frustrating – his Liverpool sojourn particularly. It’s one of those pieces of writing where you’re almost begging for him to slow down, to linger, to paint the details more thoroughly. I want him to be more formal and focused and less spontaneous. But that’s probably because Liverpool is my city and I’ve always been captivated by the very idea that he came here.

SW: Your book is about a restless desire to travel, to move away, but it is also a book about family, nostalgia, the death of your father. How do you feel each separate section illuminates the other?

JY: Wild Twin begins where it ends – in the living room of my family home in a suburb north of Liverpool. In the opening pages I say goodbye to my father as I set off on the road to Paris. In the closing pages I say goodbye to him as he lies dying in a bed in the same room. I spent a lot of 2023 looking after him with my sister. He was housebound, bedbound, struggling with physical frailty and Alzheimer’s.

As the weeks went by and the long days passed very slowly, the book began to gestate. I’d struggled to write it and I was behind schedule, largely because my own health problems meant I couldn’t physically write or mentally write. I was brain fogged to such a degree that my publishers and I thought I’d never manage to write the book. And then it came to me – the realisation that I was in THE ROOM with my father; the goodbye at the beginning of the book was echoed in the impending goodbye at the end.

The book is in three parts – ‘Part One’ is the wayward trip to Paris; ‘Part Two’ is the Amsterdam years; ‘Part Three’ is the return to the family home and the caring for my father. He features in each part and is a presence in the book throughout. The first two parts of the book repeatedly fold back to Liverpool and it’s a vision of the city informed by his vision of the city to a large degree. I recall journeys through the city with my dad when I was a child.

By the time we get to ‘Part Three’ he can no longer remember the city, can’t tell the stories he used to tell about his childhood and youth, can’t even remember where he lives. So, in my head there is a patterning between each of the three sections, a lattice work of threads. And eventually the realisation that the restless quests were always going to end up her, because the book is not really about going away, the book is about coming home.

SW: When you taught creative writing at Liverpool John Moores University did you ever introduce your student to Beat creative techniques?

I did! Perhaps not directly naming Kerouac every time but certainly using spontaneity – spontaneous bop prosody – in workshops and a lot of the work we did was about word sketching, out an about in the city, impressionistic image capture. I often used Burroughs’ Last Words: The Final Journals in lectures.

Each year I gave a lecture about Journals and Notebooks, and I used Burroughs’ final diary entries to illustrate how a writer such as WSB, with all his dark and difficult character traits, could arrive at some kind of thoughtful peace wherein he contemplated the power of love.

And cut-ups were part of writing workshops games, a playful way of disrupting the imagination and showing how dissonance can play a part in narrative construction – or deconstruction. A lot of my younger students were interested in Beat culture, particularly the young men. They were versions of me, although they were better educated!

See also: ‘Book review #41: Wild Twin’, February 28th, 2025

Glad you picked up on various threads in the Jeff Young interview, Jose. You reference, as he did, some important Beat antecedents.

The Beat Hotel. Harold Norse was seminal author- died penniless in tawdry. Zen Francisco flophouse Henry Miller showed Beats the high road- his sexual conquests were integral to his oeuvre- the scene of him engaging in a sexcapade in a Paris telephone booth with a hooker is priceless- altho today Miller would be disdained as a macho chauvinist pig by#Me Too. His muse Anais Nin is my muse with her literary charm & sexuality of Astarte- ferry cross the Mersey Jeff Young the land I love