Interview #34: Rikki Stein

Talking Burroughs, Gysin and Joujouka

Best known for his association with Nigerian Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti, RIKKI STEIN has had a long and fascinating life in music. As a music manager he has overseen tours with a gallery of groundbreaking artists from the the Grateful Dead to Jimi Hendrix and Fela himself.

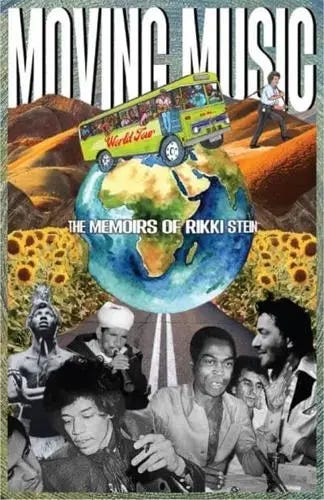

Shortly after the recent publication of his rollicking autobiography Moving Music, our contributor DAVID HOLZER connected with a man with many intriguing tales to tell.

Says Holzer: ‘Rikki told me about his friendship with Brion Gysin and Willam S. Burroughs and how living in the tiny Moroccan village of Joujouka – legendary among Beat and counterculture aficionados – between 1971 and 1973 transformed his life, that period when he forged his connection with the renowned Master Musicians Of Joujouka.’

He adds: ‘For me the highlights of Moving Music are his accounts of life in Joujouka and his time managing Fela but there’s plenty to feast on including vivid descriptions of hanging with the Grateful Dead, living on a commune, surviving Woodstock and Altamont, sitting at the feet of Krishnamurti, helping to make the Glastonbury Festival what it is today – he brought the Master Musicians of Joujouka there three times – managing African artists, who include Les Ballets Africains, Rachid Taha, Les Nubians and Keziah Jones, plastic and, as they say, much more.’

Pictured above: Rikki Stein

Holzer points out that London-born Stein, now 82, remains active in the music world as ‘the self-appointed guardian of Fela’s legacy’ and as CEO of the Kalakuta Sunrise label outside the US. ‘As someone who describes his “proper pay” as “seeing an audience transported by the music”, Rikki will, I’m sure, live and breathe music for as long as he lives.’

‘I don’t know whether he is just a born storyteller or if he learned the art in Morocco but he has a wonderful, anecdotal way of answering questions.’ This colourful exchange for Rock and the Beat Generation confirms as much…

David Holzer: What did the Beats mean to you?

Rikki Stein: I didn’t have much of a connection with them until I met Brion Gysin, William Burroughs, Anthony Balch and Ian Sommerville. By that time I had hair down to wherever and was in the follow-up crew.

I am very fortunate in having struck up a real friendship with Brion particularly. I spent a lot of time with him. He gets first acknowledgement in my book as someone who taught me what history was all about. He had this extraordinary gift of being able to tell you stories about things that happened a thousand years ago as if they were yesterday and told with this wonderful sense of dry humour.

I'll tell you a nice little William story. I had an assignation one Saturday night which finished early in the morning and found myself walking down Piccadilly at 7am on a Sunday. In the doorway of a shop there was William standing there with his hat and his coat on.

I stopped and said 'Hello, William' and he replied, 'Hello Rikki. Can I take your photograph?' I said 'Sure' and he pulled out this little Brownie camera and went click. 'Can I take your photograph?', I asked. He said 'Sure' and handed me the camera. Click. I handed the camera back. He stepped back into the doorway and I continued on my way (chuckles).

Pictured above: Stein’s new autobiography Moving Music

DH: How did you end up in Joujouka?

RS: I'd just brought the Grateful Dead to Paris and a dear friend of mine called Ronnie Bird, who was at that time the boyfriend of Françoise Hardy, had just got back from Morocco. He said, 'Rikki you have to go to Morocco, OK?’ I replied, ‘I’m broke right now but when I've got some money I'll go.' And he said (adopts portentous voice) 'No, no, no. You have to go to Morocco' and I replied, 'OK'.

The next day Ronnie rolled up with a fistful of banknotes, banged them down on the table and said ‘Go to Morocco’.

Ron Rakow, one of the Grateful Dead crew and nicknamed ‘Cadillac Ron’, came up with the idea of Grateful Dead Records and Round Records and managed the Dead, used to come to Europe every year, buy a sports car, howl around Europe, fly it back to California and cover the cost of his trip. This time he’d bought a Ferrari.

‘Do you want to come for a ride?’ he asked me. ‘OK,’ I replied, and we hurtled around France for about 10 days until we were roaring down a road in deep countryside somewhere near Marseille which narrowed to a bridge and we just piled the Ferrari into it. Well, I didn’t know anything about fixing Ferraris.

I said, ‘Ron, sorry mate but good luck.’ And I went and got on a boat to Tangier.

From the moment I stepped off the boat and put my foot on Africa I felt an immediate connection. There was something taking place there that I wanted to be a part of.

I’d arrived in Tangier. Everything was cool. I booked into a hotel and went wandering around the city fascinated by what I was seeing and feeling. I went into a café and fell into conversation with an American couple. They asked where I was staying. When I told them a hotel just round the corner they said ‘No, no, no. We’ve just rented a big house with loads of room. Come and stay with us.’ I got my suitcase and found myself in a beautiful house on the edge of Tangier with the waves crashing against the rocks below, palm trees and all that.

Next morning they said, ‘We’re going to visit a friend. Would you like to come?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ We went to this house in the Medina, climbed up and up and up to the roof. There was a guy in a djellaba with his back to us painting. He spun round and he had these eyes like burning coals. This was Mohamed Hamri (laughs).

Pictured above: The Master Musicians of Joujouka, Centre Pompidou, Paris, September, 2016 Image: Herman Vanaershot

Hamri looked at me and he said (adopts accent) ‘Where you been? I wait you long time.’ I said ‘I got here as fast as I could’. ‘Wait,’ he said, and he ran downstairs and came back up with this album cover in his hand, pushed it into mine: Brian Jones Plays with the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka. [Note: This is the original name of the album better known as Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka.]

I turned the thing over and started to read the sleeve notes written by Brion Gysin that described the village of Joujouka. Now when I lived in Oregon I used to pump out this Atlantis Almanac. Every month, I took a myth and wrote about it. One month I wrote about the great God Pan.

I described the place Pan would like to live. There’d be running water. There’d be lots of pretty girls. There’d be music. And there I was standing on this rooftop in Tangier reading these sleeve notes as if I’d written them. And I said, ‘Hamri, you mean this place is real?’ ‘Yes!’ he replied. ‘You mean we can go there?’ ‘Yes!’ he replied.

The next day I found myself in this little van with Hamri driving like a maniac, saying ‘The people they sleeping. My job is waking them.’ And the horn went ‘Beep, beep, beep’ (laughs). That’s how I got to Joujouka.

DH: What were your first impressions?

RS: Wow. We arrived at the top of this mountain and found ourselves in a cloud of little boys running with us along the road. Hamri pulled up at this building and these people tumbled out, all wearing woolly djellabas and white turbans: big ones, short ones, fat ones, thin ones, old ones. They ushered me into the house and sat me down, gave me a kif pipe to smoke, gave me mint tea.

Someone picked up a flute and started to play. Somebody picked up another flute. Somebody picked up a little hand drum. This thing started and it built to a point where I just rose to my feet and I danced like I'd never danced in my life before. I was just, ah, transported. Put it that way.

I was so blown away by this place that I tore up my ticket and stayed for almost two years. Every day I was in that cloud of little boys learning to play drums.

Pictured above: Stein with Fela Kuti

DH: The great rock writer and musician Robert Palmer, who also spent time in Joujouka, described it as the mothership. What do you think the village and the music are?

RS: I once met a blind guy in Tangier selling plums. When you went by his stand he would have only three plums. I became friends with this guy. 'Why've you only got three plums man?', I asked. 'Yeah, but, they're very sweet', he replied.

One day he took me to his house and I had lunch with him and his wife who was also blind. She cooked me up this wonderful meal. Watching them move around in their house was better than ballet. The choreography was just so beautiful.

Anyway, we wanted him to come to Joujouka. He refused so we kidnapped him, chucked him in the back of Hamri’s van and drove him up to the village. There was a battered guitar sitting on one of the settees. He picked up this thing, shook it and banged it and suddenly this fucking symphony came out of this battered guitar. All of us, including the Masters, were just sitting there open-mouthed. He was protesting at having been kidnapped but it was all so beautiful.

What I’m saying is there’s something in the air of Morocco, in the air of Africa.

Robert Palmer brought Ornette Coleman to Joujouka to play and record. Ornette was having difficulty gelling with the musicians. Robert went and sat down with his clarinet at the end of a line of rhaita [a double-reed, oboe-like instrument] and just synced in perfectly with what was taking place. He wrapped his music around Ornette and dragged him into the thing.

DH: Do you think the music of the Master Musicians of Joujouka is healing?

RS: Yes, and I can give you an example of that. I invited a friend to come up during the time I was living there. He arrived with his girlfriend who was, what's the best word to describe her, catatonic. She was really in a mess, man. And he wanted her to have the healing.

Normally people would come and they'd bring a chicken, they'd bring a torpedo of sugar. The musicians looked at this girl and said 'Rikki, she needs a sheep' (chuckles). So my friend Joel bought this sheep and they took her to the sanctuary, around the tomb of wandering Sufi saint Sidi Hmed Shikh who gave the masters the power to heal madness and infertility. The tomb is, as musicologist Philp Schyler wrote, ‘the spiritual and geographic center’ of the village.

They played the Kaimanos, their healing music. When it was over the girl laid herself down flat on the ground. It wasn’t obeisance. The musicians came round and pressed their feet and instruments on her and the girl stood up and went and cooked lunch for everybody. I mean, come on man.

When you first hear that music it’s quite painful. The second time, it’s a little easier but still very powerful. Third time, it’s cool. That music works man.

DH: What do you think Joujouka gave you in your life?

RS: It amplified my sense of wonder.

DH: Do you still listen to the music?

RS: Yes I do. I particularly like the recording made in the Centre Pompidou in 2016. I can never stop listening to the music.

DH: You went on to have a life in music with Fela and other African artists. Did your time in Joujouka change your attitude towards the rock and roll you grew up on and which was your stock in trade when you started in the business?

RS: I feel like in Joujouka and other places I’ve been the healing aspect is something that’s primordial. You can’t fuck around with it, you know? Fela always used to say ‘Don’t fuck around with music, man. You’ll come unstuck.’

Whatever we aspire to and wherever we get our jollies from is what turns us on. It doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy Jimi Hendrix or the Kinks or other people I’ve worked with. African and Western music both have relevance. The difference is one of intent.

Further information: Moving Music is published by Salamander Street/Wordville. It is available as an audiobook. You can listen to the Master Musicians of Joujouka at the Centre Pompidou and find out more about experiencing them in the village here.

Editor’s note: David Holzer is a writer and independent Beat scholar who has written extensively on Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg as well as Herbert Huncke and Mason Hoffenberg, co-author of the novel Candy. He has a particular interest in the Burroughs/Gysin Dreamachine and the music of Joujouka. Dividing his time between Mallorca and Hungary, Holzer is a member of the European Beat Studies Network and has had a number of articles published in enduring British Beat magazine Beat Scene, including pieces on Bowie and Burroughs' summit meeting, Kerouac and sound, David Amram and the British writer Terry Taylor.