RON WHITEHEAD – ‘crazy as nine loons’ according to his late friend Hunter S. Thompson – is an award-winning poet, author, editor, teacher and activist, a visionary word-slinger who shoots from the lip, bullets grazing your head in ‘a dazzling mix of folk wisdom and pure mathematics.’

In the first of an extended, two-part exchange, regular Rock and the Beat Generation interviewer LEON HORTON goes beak to beak with the legendary US poet to discuss his life, work and his new book Crow and Outlaw: New and Selected Works, which includes an introduction by the great musician David Amram.

Released earlier this year through Keeping the Flame Alive Press, the new volume is celebrated by Kentucky Poet Laureate Lee Pennington as ‘poetry real, magical, mystical and stunningly powerful’ – an accolade fit for a mountain.

Horton delves deep into the craggy life of an extraordinary artist with talons still firmly gripping the branch of Beat. His conversation with Whitehead is both vivid autobiography and, at times, a work of epic verse in its own right…

____________________________________________________________________________

Leon Horton: How did you make your poetic choices for the book? Is there a running theme or philosophy?

Ron Whitehead: I rise and shine every morning at 3am, the time when the veil between worlds is thin, in the quiet hours before dawn, when most of the world still sleeps. My goal is to write a new poem or story every day, which I then add to a Google doc. The doc contains both new works plus old(er) works I continually reshape into new works. The doc presently contains five hundred pages of poems and stories. So when I receive an invitation from a publisher I have plenty of material to choose from. Since I was a boy, Crow has lived on my left shoulder. As a teenager I chose to be an outlaw, to live outside the law, to be honest.

LH: What is the significance of the Crow? I often think of Hunter S. Thompson as a personification of Coyote, the trickster god, and there are many interpretations of the Crow in mythology: sometimes a good omen, of transformation, wisdom and intelligence, but also representing death or misfortune. Is the Crow your spirit animal?

RW: Crow and Outlaw: When I was a boy Daddy taught me how to talk with crows. One winter's day we went hunting. A murder of crows flew near. Daddy said, ‘Boys, watch this.’ Then he called them. He lifted his shotgun and shot one out of the sky. It fell, wounded, near us. Daddy put his foot, lightly, on the crow. The crow let out a godawful scream. The other crows screamed. More came. They all flew right above us. Daddy shot another one. When he left to get the other crow I knelt and silently spoke to my dying friend. When it died its spirit lifted up and perched on my left shoulder, where it has remained for all these years.

From time to time, my crow travels to who knows where and returns with poems. One time my crow left for a week. Here's what Crow brought back: ‘Is the span of my life, or your life, of a crow's life measured in exact time? What gives you the right to assume that you are more intelligent than a crow. For an idiot you're all alone, standing in a field full of idiots. From the dark recesses of an old church basement a crow and a self winding clock turn the lights on and off on schedule. Did you know that in 1733 Lancashire England John Kay patented the flying shuttle. And, in 1760, John's son Robert invented the drop box. Spinning and weaving, from hand production to steam powered machines, the Industrial Revolution was born. The Industrial Revolution sold exact time. Crows use tools. Crows make the tools they use. The potential for democracy has a perpetually westward movement. Democracy is not a self winding machine. What does that say about exact time. A crow knows what exact time is. A crow is aware of the wisdom and the futility of a machine world. Crows score high on intelligence tests. Crows laugh hysterically, Caw Caw Caw, when the subject of humans testing crows comes up. Crows spin tales. Crows weave time. Crows are cawing mathematicians. Crows know which way the wind blows. Crows wrote the I Ching, the original book of changes’

Pictured above: Ron Whitehead’s Crow and Outlaw, published earlier this year

‘ON BEING AN OUTLAW POET’:

‘The Ending of Time, An Alchemical Rant’

‘To live outside the law you must be honest.’

– Bob Dylan, ‘Outlaw Poet’

‘An outlaw can be defined as somebody who lives outside

the law, beyond the law, not necessarily against it. By the

time I wrote Hell’s Angels I was riding with them and

it was clear that it was no longer possible for me to go back

and live within the law...There were a lot more outlaws than

me. I was just a writer. I wasn’t trying to be an outlaw writer.

I never heard of the term, somebody else made it up. But we

were all outside the law, Kerouac, Miller, Burroughs,

Ginsberg, Kesey, me. I didn’t have a gauge as to who was

the worst outlaw. I just recognized my allies, my people.’

– Hunter S. Thompson, ‘Outlaw Writer’

‘I Refuse, I Will Not Bow Down, and I Will Never Give Up!’

– Ron Whitehead, Outlaw Poet

‘Time was. Time is. Time will be no more.’

and it’s the big bang epiphany

in the gap between thought and image

voices streams racing

whispering through my throbbing blood

pleading through my dancing bones

strange activities of my laughing nerves

the unconscious life of the ecstatic mind

a tetrameter of iambs marching

shouting

alchemically transmutative symbol decipherment

the book as sacred elixir

manger du livre

eat the book

and the words

will set you free

'The shortest distance between two points is creative distance.’

and Allen Ginsberg howls

‘I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

Madness, starving, hysterical naked’

and Diane di Prima rants

‘The only war that matters is the war against the

imagination all other wars are subsumed in it’

and Amiri Baraka chants

‘They have turned, and say that I am dying, that

I have thrown

my life

away. They

Have left me alone, where

there is no one, nothing

save who I am. Not a note

not a word.’

and William S. Burroughs eats

Naked Lunch

and Gregory Corso pours

‘Gasoline’

and David Amram sings

'Pull My Daisy’

and Herbert Huncke is

‘Again, The Hospital’

and Neal Cassady died naked

on those long distance railroad tracks to nowhere

and Lawrence Ferlinghetti paints

'‘Pictures of The Gone World’

and Jack Kerouac is still

On the Road

Mysterium tremendum Gnostical turpitude

Allen Ginsberg Diane di Prima Amiri Baraka

William S. Burroughs Gregory Corso David Amram

Herbert Huncke Neal Cassady Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Jack Kerouac

numinous howls and rants and chants and paintings

and years of tears come fiercely flowing streaming

all the pain wells up

years of failure of not being enough for anyone

years of wandering lost on the outside

outlaw

being told ‘You ain’t shit you don’t fit what the

fuck are you doing here? All you’ve done is

create pain and sorrow

wouldn’t you be better off dead?’

turning away from walking away from disappearing from

bullies authorities tyrants the past the dead

in the hermetic corridors of authority the dead

somberly splash in their shallow sewers

devouring and regurgitating themselves

and with tears in my eyes a snarl on my lips and

peace in my heart

I’m failing as no other dare fail

and I’m in the gap between thought and image

how’d I get here after all the years

of not being self

after all the years of being other

of floating out of my body on the ceiling

watching skin blood bones nerves going through the motions

believing in space and time without realizing I was already

out out of sync beyond chaos

breathing rhythms at the ending of time

and now here in the gap between thought and image

where the only distance is creative distance

here now at the ending of time

I focus all three eyes in wolf fashion

closing time

I walk through the stone

I float through the fire

I enter the upper chamber

and the crystal tip of the golden pyramid

the confluence of all streams

polyglot commingling of all voices

Thalass feeds herself

and as I float over the open sarcophagus

I am

the ocean of consciousness

LH: Kentucky (your birthplace) is present, of course, and looms large across the greater body of your work. It is something of a rhetorical question for a writer, but how important were your formative years to your development as a poet?

RW: No matter where I wander, no matter how far I roam, the most beautiful place on the planet is always singing my song, calling me home. The place and the people shaped me, helped make me who I am. Until the day I die I’ll be thankful, I’m forever Kentucky bound.

LH: There is a spirituality to Kentucky in your writing. Is it fair to say there is also a mythical quality?

RW: Raised by birds and dogs, I slept on grass, near the woods. I wander with one foot in this world and one in spirit realms. Nature keeps my enlarged heart soft. Tears run from my eyes with unexplainable joy. I have conversations with beings from other worlds. History is the little myth created by victors. Poetry is the big myth that perpetually rebirths us. Humans were invented by dogs, to do their bidding. The Middle Way is best found by watching the clouds. Clouds look far different in day than in night. I have always searched for those weird enough to be wise. Through tall cedars and pines we race, one stride ahead of fires and flood waters. Once upon a time, I created seven authors. Each wrote in a different genre. These days, all my characters write me, the solo author of their works. It is less and less a problem for me to get out of my own way. Some days, I'm barely here. That's when I'm gone baby gone. Some days I hold time and timelessness in the palm of my hand. How many more times will we see more than can ever be put into words. I get all my news from poems. We live in the most interesting times.

LH: When did you start writing poetry? Who were your first poetic influences? Did your parents encourage your imagination?

RW: Thanksgiving in Kentucky

I always loved to climb. It was Thursday, a warm Thanksgiving Day. I climbed to the top branch of the maple tree in our front yard. Even though I was thin, the limbs swayed with my weight. I was watching for my Render relatives, coming from Louisville to visit for the weekend. We're a huge family, the size of a small army. Mama's the oldest of thirteen. I'm her oldest. She's our mother but she's also second mother to all her sisters and brothers.

When the Renders came to visit, which was often, we slept everywhere: on army cots, on couches, in chairs, on floors. eight to a bed: four at the top, four at the bottom. We slept in tents and in cars. Sometimes folks slept in the hay in the barn.

Grandaddy and Mamaw will be coming over the hill, in the distance, any second. They'll be followed by at least three or four more cars, filled with Renders and their families, and I'm gonna make sure I'm the first to yell real loud, ‘Here They Come!’

I loved to hear my brother and sisters scream, while running all over the yard, ‘They're coming! They're coming!’ And I had to be all the way up in the top of the tree so I'd be the first to see them so I climbed and I climbed all the way up to where the limbs were so thin the branches started to sway back and forth. I had the best balance. I held on tight. I swayed with the branches in the breeze, high atop the giant maple tree, and that's when my brain began to sing and my heart pounded with joy. And in that moment I saw them and I yelled, ‘Here they come! Here they come!’

Mama and Daddy are here in the kitchen with Mama's parents, Mamaw and Grandaddy, and some of their kids, my aunts and uncles: Adeline, Kendall, Linda, Becky, Donna, Danny Boy, Stevie, and Timmy plus my brother Brad and our sisters Paddy and Edie. Edie's just four months old. It's Thanksgiving. I turned seven today. Daddy's home from the mines.

Thanksgiving Day. My Louisville relatives are visiting. I'm excited by all the family energy, by the laughing, the loud conversations, the singing. We love music. There are many singers and musicians in our family. Mama and Grandaddy are singing, "When They Cut Down The Old Pine Tree." Grandaddy is playing the ukulele. Daddy asks me to recite the "Trees" poem. In certain situations I'm shy, but I finally find the courage, so I stand straight, take a deep breath, and let go:

‘Trees’ by Joyce Kilmer

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth's sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow was lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me.

But only God can make a tree.

I spend most of my time in nature and feel close kinship with trees so I memorized the ‘Trees’ poem right after I first read it. Everyone is clapping and yelling. The kitchen is full of family. People fill the two doors, one leading to the utility room and the other to the living room. They're leaning in, looking over shoulders, to see and hear. I turn to Daddy and say, ‘Do “Hiawatha”.’ I love that poem and I love to hear Daddy recite it.

‘The Song of Hiawatha'

part XXII

Hiawatha's Departure

By the shore of Gitche Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

At the doorway of his wigwam,

In the pleasant Summer morning,

Hiawatha stood and waited,

All the air was full of freshness,

All the earth was bright and joyous,

And before him, through the sunshine,

Westward toward the neighboring forest

Passed in golden swarms the Ahmo,

Passed the bees, the honeymakers,

Burning, singing in the sunshine.

Bright above him shone the heavens,

Level spread the lake before him;

From its bosom leaped the sturgeon,

Sparkling, flashing in the sunshine;

On its margin the great forest

Stood reflected in the water,

Every treetop had its shadow,

Motionless beneath the water,

From the brow of Hiawatha

Gone was every trace of sorrow,

As the fog from off the water,

As the mist from off the meadow,

With a smile of joy and triumph,

With a look of exultation,

As one who in a vision

Sees what is to be, but is not,

Stood and waited Hiawatha.

Daddy knows the entire poem but he just recites the last section tonight because it's a long poem and others are gonna sing and play. Everyone is spellbound by the music of the poem. I've seen tv and movie westerns but ‘Hiawatha’ helps me feel and see deeper into what I imagine the Indians are like. I wonder why they are called Indians. Who are they? What are they really like?

This is a special moment, listening to Daddy recite the poem, seeing everyone pay close attention, listening to the story. I'm waking up to a new mystery, to many mysteries. I want to know about the lives of these strange people everyone called Indians. Why do I feel close to them?

I realize now that I'm a poet. My mind isn't sure what it means but my heart knows and that's enough for now.

Daddy is a farmer and a coal miner. He's worked hard all his life for Peabody Coal Company and has never missed a day of work. He's the strongest, hardest working man I've ever known. Daddy loves poetry. He knows many poems by heart. He encourages me to learn poems and I do. I already know quite a few. Daddy always asks me to do "Word Power" with him when the Reader’s Digest arrives in the mail. Words, poems.

The spirit in poetry brings Daddy and me close. My heart grows big. I hold back tears. I am thankful.

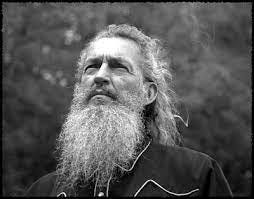

Pictured above: Poet Ron Whitehead

LH: You are a prolific writer by any standards – over 40 authored collections, and over 40 audio recordings – but are you much of a rewriter? Is first thought best thought?

RW: First, I let go, let it flow, first thought best thought. Then I do lightning fast edits. Numerous edits in a matter of seconds, of minutes. But before I write I have to have something to write about so I listen. Listening is the greatest art of all. I learned to listen to my heart, my intuition, to the voice(s) coming to me through the wind, the wind coming through cedar and pine, whispering through the holes in my attic walls. I listen, then I write, then I edit, then I share.

LH: I think of you as very much a performance poet – dare I say, a shamanic, rock star poet. I still covet that jacket of yours, but is it accurate of me to perceive you that way?

RW: Thank you! Poems must stand up on the page and on the stage. I’ve presented a few thousand performances of my work in over 20 countries around the world. Some poems work better for live performance than others. But those poems must also stand up on the page. And like the ancient bards I realise that when I perform a poem it must be filled with a lightning electric energy that connects with the listeners on the deepest emotional levels.

The last thing I want to do is bore the fuck out of listeners. Boredom is a killer. You ever go to an academic poetry reading? I’ve been to too many of them. And I learned quickly that I better drink a few extra cups of coffee ahead of time so I can stay the fuck awake. So many academic poets read their works in a fucking boring ass tick tock monotonous metronomic monotone that’ll put you right to sleep. I want to engage, to entertain, to grab the listeners by the collar, pull them up into my face, stare them in the eyes and say Listen, I’ve got something to say so Listen, please. And when you present your work I’ll do the same, I’ll listen!

LH: Is poetry purging? I don’t mean therapeutic, so much, and I don’t mean emetic. Actually, I’m not sure what the fuck I mean…

RW: Poetry is purging, therapeutic, emetic, a journey through the known and into the unknown. Poetry embraces not knowing.

LH: Should poetry always be sincere? I think it was Gregory Corso who once said some of his best works were lies.

RW: Poetry can be whatever the fucking poet decides it’s gonna be. But whatever it is it best be engaging, otherwise the poet will be reading his work to himself.

LH: Corso appears in Crow and Outlaw (‘As Corso Stumbled Away’) and Kerouac features in several poems. The Beats have been an important influence on your work, but what do they mean to you on a personal level? Are they still relevant?

RW: Corso in Louisville. When Gregory got off the plane he yelled, ‘I wrote new poems for you!’ Then he leaned over and softly said, ‘And all I need is heroin. And I'm not just talking about any heroin, I'm talking about the best.’ I looked at him and said, 'Gregory, Allen called me two weeks ago and had a long talk with me about your visit.’ He said, ‘Whatever you do, don't buy him heroin. I spent too much time and money getting him off of it. So, Gregory, I can get you anything else you want, anything, but not heroin.’ Steam started coming out of Gregory's ears. His face turned red then he yelled, ‘That fuckin' Ginsy! I'll kill that fucker! Soon as I get back to New York I'm gonna kill him! Oh, he used to do everything but then he got sick and cleaned up his act and now he's Mister Goody Two Shoes! That bastard! I'll get him!’

Gregory had arrived for a four days and nights visit and a reading at the University of Louisville. Three days later, Corso came barging into the auditorium for his reading. He was yelling and screaming, cussing and calling me every name in the book. When I took the microphone to introduce him he started circling me, yelling louder. I stopped, turned, grabbed him by the shoulders and said, ‘Gregory, most of these people don’t even know who you are. Let me give my introduction and tell them a little about you. Then you come out and read. I gave a kickass introduction. Gregory gave an incredible reading. After David Amram watched the film footage of the reading he said, “Gregory’s Louisville reading was the best reading he ever gave.”’

Neal Cassady died in 1968, Jack Kerouac in 1969, so I was too young to hook up with them but I ended up being blessed to work with Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Herbert Huncke, William S. Burroughs, David Amram, Diane di Prima, Amiri Baraka, Anne Waldman, Ed Sanders, Hunter S. Thompson and so many other members of and those closely connected to '‘he Beat Generation.

I am often asked, ‘What does being Beat mean? What was and what is the Beat Generation?’ My brief response is, ‘Being beat down, even broken, but maintaining spiritual integrity. Helping others, even when I have no material gifts to give.’

‘The bus roared on.

I was going home in October.

Everybody goes home

in October.’

– Jack Kerouac

I stood at Jack Kerouac's grave, in Lowell, Massachusetts, shoulder to shoulder with his daughter Jan. Jan Kerouac is long dead now too. Their white bones buried coast to coast, ghost to ghost. I see them now, holding hands, far seeing, staring at me from spirit realms, Jack and Jan Kerouac, staring at me writing this poem, searching for them and I hear Jack say, ‘The Beat Generation, that was a vision that we had, John Clellon Holmes and I, and Allen Ginsberg in an even wilder way, in the late Forties, of a generation of crazy, illuminated hipsters suddenly rising and roaming America, serious, bumming and hitchhiking everywhere, ragged, beatific, beautiful in an ugly graceful new way – a vision gleaned from the way we had heard the word "beat" spoken on street corners on Times Square and in the Village, in other cities in the downtown city night of postwar America – beat, meaning down and out but full of intense conviction. We'd even heard old 1910 Daddy Hipsters of the streets speak the word that way, with a melancholy sneer. It never meant juvenile delinquents, it meant characters of a special spirituality who didn't gang up but were solitary Bartlebies staring out the dead wall window of our civilization...’ Then Jack adds ‘The World really does not matter, but God has made it so, and so it matters in God, and He Hath Aims for it, which we cannot know without the understanding of obedience. There is nothing to do but give praise. This is my ethic of “art”…’ And searching for Jack Kerouac I realise that I don’t know anything, nobody knows anything, but I embrace this fiercely beautiful mystery, this mysterium tremendum called life, and I declare that henceforth and forevermore I will do nothing but surrender my will to the creative forces of the universe and sing songs of praise of thanks of joy of happiness. Even as I lie dying, I’ll sing songs of grace and gratitude.

The Beat Generation poets, writers, artists, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, our inspirational life-affirming ancestors, are people who have stood and still stand up against unreasoning power, looked that power in the eyes and said ‘NO! I REFUSE! I don't agree with you and this is why.’ And they have spoken/written those words, not for money or fame but out of life's deepest convictions, out of the belief that we, each one of us, no matter our skin color economic status, our political religious sexual preferences, our immigration status, all of us have the right to live and dream as we choose rather than as some supposed higher moral corporate military political religious power monger authority prescribes to us.

In the next decade the Beat Generation will come to be recognized as the most important group of poets and writers in the history of America. The Beats have given birth to new generations to new energies which are waking to the realisation that the creative imagination provides salvation from suicide, from death in life, by revealing that there are alternative paths to explore in this world, alternative paths that lead away from the mundane, the superficial, away from submission to mediocrity, alternative paths opening into the inspired brilliant fire called LIFE!

LH: Tell us something about your relationship with Allen Ginsberg…

RW: When Allen Ginsberg put the O in HOWL a long time ago I sold books from San Francisco, from Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City Lights Books, 261 Columbus Avenue, North Beach, including books by Allen Ginsberg and all the poets and writers of the Beat Generation, in our underground bookstore, For Madmen Only, on South Limestone in Lexington, Kentucky.

In 1992, I brought Allen Ginsberg to the University of Louisville for a reading. 1,500 folks attended, a record attendance for a poetry reading in Kentucky. Ginsberg visited for a week. The night after he left he presented a reading in Lowell, Massachusetts, at the annual Lowell Celebrates Kerouac Festival. He told the audience, ‘If you don't know who Ron Whitehead is down there in Kentucky you better find out.’ In the last five years of Ginsberg's life I worked with him on many creative projects. I published several of his poems and photographs. He opened many doors for me.

A year after Allen's death, legendary rock journalist Al Aronowitz and I produced ‘The Allen Ginsberg Tribute’ at the Naumberg Bandshell in Central Park. Ginsberg editors and publishers and fans from around the world attended, including Michael Dean Odin Pollock and his brother Danny and Birgitta Jonsdottir, from Reykavik, Iceland. They invited me to Iceland to give three readings. I ended up staying for a couple of years.

On October 7th 1955, when Allen Ginsberg put the O in HOWL I was almost five years old, a wild nature country boy growing up on a backwoods Kentucky farm. When Allen Ginsberg put the O in HOWL, the earth's magnetic poles shifted, the tectonic plates collided, there were earthquakes and volcanoes, the Mississippi River flowed backwards. When Allen Ginsberg put the O in HOWL business men ripped off their neckties, housewives swallowed amphetamines, Joseph McCarthy started drinking himself to death, J Edgar Hoover put on his pink tutu and danced, Anne Sexton had her 2nd manic episode and was encouraged by her therapist to take up poetry. When Allen Ginsberg put the O in HOWL outsiders got stoned, outlaws wailed and moaned for man. When Allen Ginsberg put the O in HOWL.

LF: You were good friends with Lawrence Ferlinghetti – you worked together on various projects, you nominated him for the Nobel Prize in Literature. I might be misremembering this, but wasn’t there talk of you writing a biography of him?

RW: Ferlinghetti deeply appreciated the biographies written about his life and work but he didn’t feel that they had delved deep enough so, yes, he asked me to write a biography that would go all the way until the wheels fell off and burned. I agreed. I did research and interviewed him several times but I finally told him I was simply too busy with my own creative work to devote the necessary time, which I felt was at least five deep dive years, and so I would, unfortunately, have to pass. I suggested, as I had to Diane di Prima, that he write his own autobiography. He said, ‘There’s too much to tell. Why don’t you write your autobiography.’ I said, ‘There’s too much to tell.’ We both laughed.

Editor’s note: The second part of Leon Horton’s interview with Ron Whitehead will appear in the pages of Rock and the Beat Generation soon. Crow and Outlaw: New and Selected Works (2025) is published by Keeping the Flame Alive Press and available on Amazon and through all good bookstores.

About the interviewer: Leon Horton is a UK-based countercultural writer, interviewer and editor. He is the editor of the acclaimed essay/memoir collection, Gregory Corso: Ten Times a Poet (Roadside Press, 2024). He also interviewed author Victor Bockris for The Burroughs-Warhol Connection (Beatdom Books, 2024). His essays and interviews have been published by Beatdom, Rock and the Beat Generation, International Times and Beat Scene.

See also: ‘“My Talk with Bob Dylan Last Night” by Ron Whitehead’, July 18th, 2023; ‘Beat Soundtrack #24: Ron Whitehead’, October 17th, 2022; ‘Ginsberg Memorial #1: Ron Whitehead’, April 5th, 2022; ‘“Searching for Jack Kerouac" by Ron Whitehead’, February 21st, 2022

A timeless sage whose conversation with Leon Horton is as rich and deep and sweeping as an ancient epic or a Nordic saga. When Ron Whitehead talks he speaks in a poetry which spans the eons…

This was my absolute privilege.