FRANCIS KUIPERS is a musicologist and virtuoso guitarist who makes his home in Italy and worked on film scores for the directors Godfrey Reggio and Abel Ferrara. In 1988, Gregory Corso with the Music of Francis Kuipers was released on the Red Record label. Kuipers performed live with Corso.

This interview was conducted by leading Beat scholar KURT HEMMER, living just outside of Chicago, Illinois, via email with Francis Kuipers in Rome, Italy, on June 22nd and July 13th, 2025. A mutual friend, Bobby Yarra, suggested that Hemmer interview Kuipers. This is part of Hemmer’s research for his work in progress The Poem Human: A Biography of Gregory Corso.

Hemmer has a significant track record as Beat historian and biographer, commentator and filmmaker. He is also the secretary of the US-based Beat Studies Association.

_____________________________________________________________________

Kurt Hemmer: Francis, can you tell me a little about your background? How did your family get from the UK to Holland? How did you become such an accomplished musician?

Francis Kuipers: All of them possessing dual nationality, my grandparents and parents were forced to leave for Britain when Germany invaded Holland to escape imprisonment. As a result, I was born in 1941 in a hospital in Woking, UK. At that time, my parents were living in a primitive caravan in a field of mud. My father, an economist, who had first been enrolled in the Dutch army, then served as an officer in the British army. When the war ended, he returned to civilian life, and we returned to Holland by military ship. I well recall that our hometown, Tiel, was mostly bombed flat.

I have been involved with music since the age of 15. I’ve played guitar and sung professionally all my life and have done many broadcasts and radio series. On my travels, I collected and studied global ethnic music. This developed into ongoing research on the functions of sound. I am much concerned with the environmental issue of sound. My vast sound archive is unique.

KH: When did you first come across Corso’s poetry and how did it strike you?

FK: I first read ‘Bomb’ by Gregory Corso in Holland in the ’50s when, still at school, I was involved in producing KLAT, the innovative Dutch poetry magazine published by Ritsaert ten Cate. Contributors included Hans van Sweeden, Jan Cremer and Simon Vinkenoog. During the Cold War, European adults insisted that the young followed rules written in stone. Used to restricted freedom, I was stunned by ‘Bomb’ and strongly affected by the explosive force of the Beats.

Counterculture spread with the speed of a bushfire. Young people wanted to break free from existing schemes and from their past and from themselves, and because they wanted to stay themselves. Every young person who wanted to be free identified with the Beats.

Pictured above: Guitarist Francis Kuipers

KH: When did you first meet Gregory?

FK: I think we first met in Rome around 1986.

KH: Why did Gregory move into your apartment in 1987?

FK: Because Gregory and I were friends and my wife and I had a room for him.

KH: What was is like living with Gregory?

FK: In 1987, Gregory lived at my apartment in Trastevere for a number of months. He slept on a mattress on the floor of the tiny room that I used as a studio. Gregory was a perfect guest, both my wife and I loved having him, and he became my son’s godfather. Before mass tourism and with less gentrification, Rome was a lot of fun in those days. For a start, it still had clubs with great live music.

The city attracted some incredibly talented artists and musicians from all over the world. Eventually, my wife somewhat tired of Gregory, especially after he brought a sweet Scandinavian girl back home to sleep with him in the middle of the night. His departure was no problem. He was welcome at my friend Maurizio Raso’s place nearby (where he remained for months also) and he dropped into see us whenever he felt inclined.

Gregory and I continued to do shows, usually big official events and universities, and we spent time on the road together, staying in the same hotels. ‘Set it up!’ Gregory would urge me with a roguish grin when he was in the mood and felt prepared. He insisted that we only did quality shows. ‘First find out what it is, then where it is, then at the end you talk about the money!’ he would tell me.

Well-off amateur, or would-be, poets were always trying to involve him in their ambitious self-aggrandizing schemes. He was offered sizeable sums by some poets eager to share the stage with him. They even provided important theatres with all expenses paid, but, above all, stipulated that they had to be top of the bill! Gregory had an answer prepared for that: ‘OK, that’s fine. We’ll take the money, but on one condition, that we go on first!’ After that, we seldom heard from the poets again. They didn’t dare go on stage after Gregory because, as in a familiar ritual, most of the audience invariably followed him out of the hall to some nearby bar or hostelry where, over drinks, his show really took wing.

Gregory’s energy was contagious and he could be incredibly funny. He constantly generated joyous and outrageous pandemonium, drawing in all kinds of persons. The possibilities of art were limitless, but you can’t do without beauty and humour, he maintained.

Pictured above: Poet Gregory Corso

‘Poetry is OK, it’s poets that fuck it up!’ Gregory used to say. Unless it was Allen Ginsberg or some other Beat Generation big shot, or an eminent artist like Francesco Clemente, Gregory avoided any kind of artistic collaboration. ‘People do terrible things!’ he once said, glancing nervously over his shoulder.

It has been pointed out to me that Gregory must have trusted me a great deal to want to work with me. He was certainly wary of me at first. Coming from a hellish background, he didn’t give his confidence easily. There were some nerve-wracking moments and disagreements, but we soon became family. Our shows were largely improvised; you never knew what was going to happen. Success was more enjoyable won against the odds for Gregory. Relying on intuition, he enjoyed playing precarious games with the audience. When matters risked getting out of hand during a show it was like walking on a tightrope or balancing on the edge of a razor.

‘Lady Poetry came to me!’ Gregory would say. ‘Allen and the others grew up with books around them, their parents had books in their libraries. They searched out poetry, but Lady Poetry came to me, in prison, to save me!’ Gregory mostly wrote his poems down on paper in parks, bars and cafés. All he needed was a place to sit and linger for as long as possible. His brain was always busy with his poems, however, honing them and fine-tuning. A quantity of his work was lost. Usually, his only luggage consisted of a used plastic shopping bag that he repeatedly forgot somewhere.

With Gregory, life could be full of merriment and surprises but hardly smooth sailing. On the road, after a night of carousing and emptying hotel minibars of alcohol, he might fall asleep with a lit cigarette, setting fire to bedclothes and mattresses. When reprimanded by Allen for his bad behaviour in hotels, Gregory was sorry and racked by guilt. I suspect that his irresponsibility, and the damage he caused, didn’t upset him in the slightest, but he was worried whenever he caused a problem for Allen.

Gregory loved Allen and felt beholden to him, knowing also that he owed his fame and economic survival to him. Allen untiringly promoted the Beats, many of whom were acquainted with each other through him. Gregory told me Allen was curious about me because he liked our LP. Without Allen’s faith and organizational ability, the Beat Generation wouldn’t have existed as a movement.

In 1997, on his deathbed Allen's final word to Gregory was a jolly ‘Toodeloo!’ After he told me about this back in Rome, Gregory asked me urgently what I thought ‘toodeloo’ meant.

‘Maybe, it means “see you soon”!’ I answered.

‘Yeah, I thought that, too,’ Gregory replied looking briefly troubled. ‘I'm the next!’

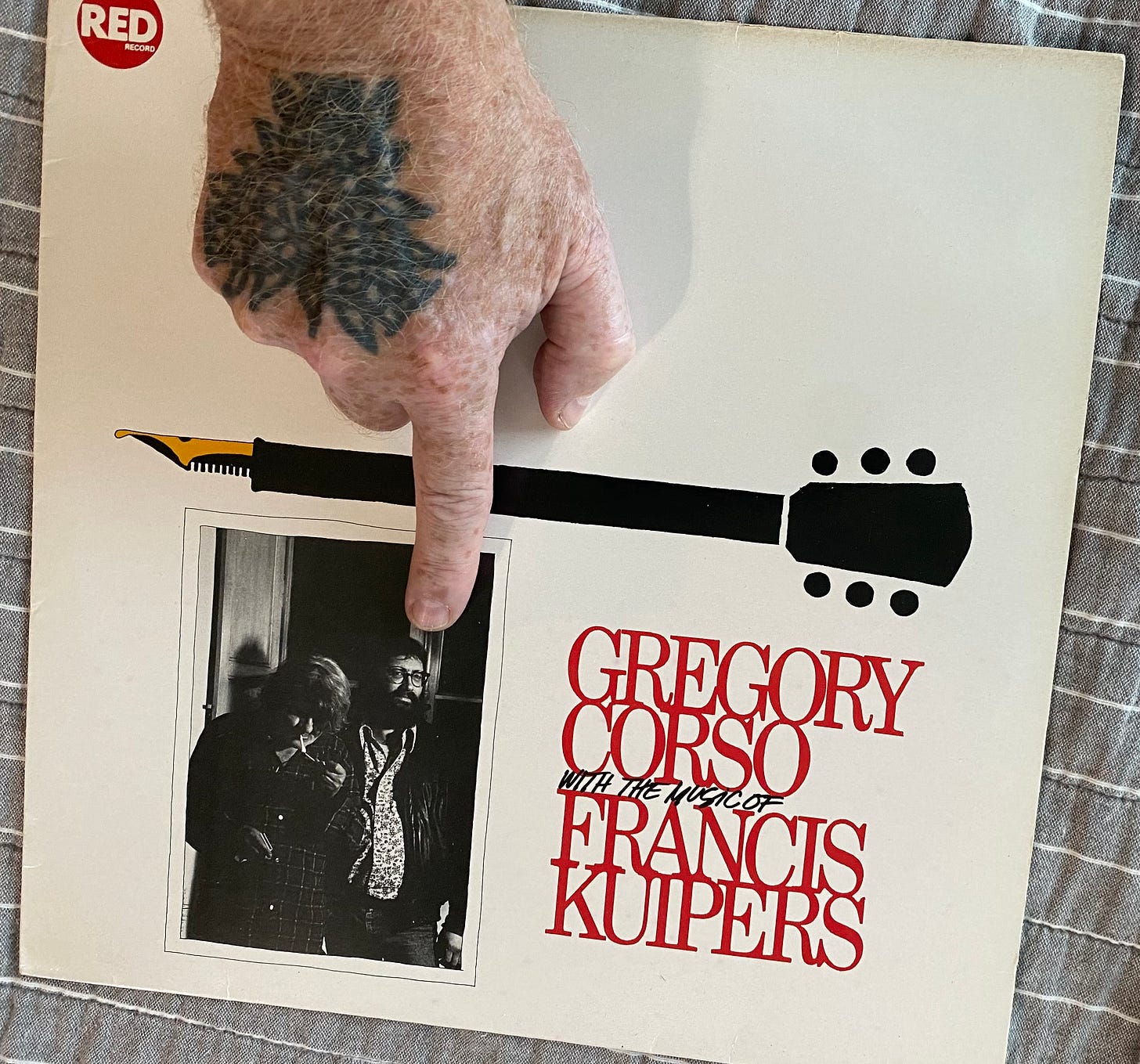

Pictured above: The 1988 album collaboration between Corso and Kuipers

KH: Do you know how Gregory got money to go out at night?

FK: Apart from earning money from our gigs, he sold his drawings and, as was common practice with a number of Beat junkies, he habitually hit all kinds of people up for cash, but not me.

KH: Did you and Gregory spend time together or communicate after you lived together?

FK: In New York, I saw Gregory regularly when I was working on the nature film Anima Mundi with director Godfrey Reggio and Philip Glass in 1991. We created a film-studio in a loft on West 3rd St., in the building in front of the Blue Note Jazz Club, easy walking from Horatio St. in the West Village where Gregory stayed with Roger and Irvyne Richards. I’d visit Gregory there (the arms of his wooden chair were scored with multiple burn marks where he stubbed out his cigarettes) or I’d meet him somewhere. Otherwise, we’d party with Vali Myers, Paola Igliori and other friends.

One day, Gregory received an invite to a New York gathering in honour of Maurice Girodias and his legendary Olympia Press. Free drinks and appetizers would be served. Spruced up as best as possible, pleased to have been invited, Gregory set off downtown with Roger and myself in the evening. A recluse for many years, Irvyne stayed at home. Apart from speaking to her pleasantly over the phone, I’d never actually seen her. I’d visited Horatio St. on countless occasions, for hours at a time, and was only aware of her being there because her feet protruded from beneath a curtain! I met her in the flesh much later, when I returned to NY for Godfrey’s film Nacqoyqatsi, and was delighted to see a lovely, elegant woman.

My first impression was that we’d come to the wrong party. Instead of the renowned literati of the Olympia Press, the empty office space was crowded with square-looking women and men in cheap suits and ties, networking and conversing agitatedly. I’d forgotten that the Paris-based Olympia Press specialised in risqué erotic books. We were surrounded by famished pornographers who were eating and drinking as fast as possible, just like us.

KH: Can you tell me a little about Vali Myers and Paola Igliori, and Gregory's relationship with them?

FK: Gregory liked them both and they were beautiful intelligent women. Vali was an Australian artist and famous bohemian. When I knew her, she lived at the Chelsea Hotel or outside Positano in Italy. My dear friend Paola Igliori still lives not far from me in Italy as well as in New York and other parts of the world. A powerhouse of energy, she wrote an important book on Harry Smith and also made a film on him, amongst other unusual creative feats. Like Vali, she was on the Beat scene for years.

KH: I've heard that Gregory was more respected in Italy than in the United States. Was that your feeling, too?

FK: As far as I know, modern-day Americans rarely treat their artists well unless they’re mainstream and make money. In Europe, there was then certainly more interest in an alternative lifestyle and good poetry, as well as Black culture and jazz. Although he was manifestly proud of his Italian roots, Gregory was, in many ways, typically American. He was unique, rebellious, excessive and volatile, as well as free-thinking, superstitious and very patriotic.

In 1979, inspired by the Beats and the success of their poetry readings in the USA, theatre director Simone Carella and Renato Nicolini, the brilliant cultural assessor of the Communist junta in power in Rome at that time, organised a poetry festival in Castelporziano outside the city. It drew a crowd of biblical dimensions. Over thirty thousand young Italians, most of whom didn’t speak or understand English, sat on the ground for hours, listening, spellbound, to the poetry of the American Beats. Their attention remained riveted even during the mayhem when the stage collapsed.

Gregory was treated like a clown, and gave a clown performance for a Berlusconi TV channel in return for a large sum, but his genius was recognised by serious-minded persons. In 1987, he was awarded the Golden Lion, the highly prestigious prize awarded annually at the Venice Biennale [I was unable to verify this.—KH]. Loathe to leave Rome for Venice, he was persuaded to go there for the prize and the money that came with it. Gregory had no compunction about demanding money from people. He always wanted 100,000 lira or, later on 100 euro for personal necessities. It was his customary behaviour with those he didn’t know and, before going on the Venice stage to receive the honour, he hit up actor Walter Chiari for a 100,000 lira bill in the elevator. Carrying the Golden Lion wasn’t easy for Gregory as it was cumbersome, but he managed to bring it back to Rome.

Gregory lived poetry passionately, with every fibre of his being and soul. Understanding this, the actor Vittorio Gasman, who first recited ‘Bomb’ in Italian, told the story of a great monk of the year 1000 who explained that you have to put in something extra to achieve perfection: ‘You go inside it so profoundly you forget you are doing it. You forget it for love.’

KH: What did Gregory do or read to get the Golden Lion in 1987?

FK: I don’t know if Gregory read anything at the ceremony. I wasn’t there. Apart from the Golden Lion being awarded to great film directors, it is also awarded for great careers, etc.

KH: Did Gregory speak to you about his past? Did he say anything about his family? About the Beats or other poets?

FK: We walked a lot in NY when I had a few hours off and Gregory reminisced about all sorts of topics. One day in Washington Square, he related to me, a young man passed by, shyly handing him a handwritten piece of paper containing a poem called ‘The Times They Are A-Changing’. ‘It was Bob Dylan before he got famous!’ Gregory explained. Not long after, he pointed out a jail, where he’d been incarcerated, and where he’d recently been invited back to counsel young inmates. On another occasion, we unexpectedly came across a friendly male relative in a strange bar near the Village.

Resting in a park, we also once found his dried-out-looking uncle sitting two rows in front of us who, Gregory confided to me, hadn’t been very nice to him when he was a boy. After uneasily taking in his uncle’s sad, defeated slouch, Gregory tentatively called out his name. The effect was electric. First, the uncle became totally rigid, then he swiftly stared at us over his scrawny shoulder. It was an intense moment. I saw a grey, haunted, Italian old face dragged up from an abyss of immigrant despair and misery beyond imagining. The next second, with almost supernatural speed, the fittest and fastest old uncle I’d ever seen was on the run, crossing the traffic lights in a flash and escaping up the opposite side of the street, never looking back, his elbows pumping. He looked like a loser, but he certainly kept himself fit for his age!

Pictured above: Beat scholar and Kuipers interviewer Kurt Hemmer at Corso’s grave

KH: Where did Gregory like to go in Rome?

FK: In Rome, during the day, streetwise Gregory could often be found sitting under the bronze statue of Giordano Bruno in Campo de Fiore. Engrossed in the New York Times and his contemplations, he also enjoyed observing the low-life activity systematically going on in the piazza around him. Later in the day, when the place opened after ‘siesta’, he went to the ‘vinai’ a few steps away from the statue. A simple wineshop no longer in existence, it was frequented by locals, intellectuals and international bohemia for decades.

Joining friends, Gregory liked to kick off the evening by playing the traditional hand-game of ‘La Mora’ that required ability and intuition, in between knocking back rounds of drinks and boisterous yelling. Later in the evening he customarily headed for Pietro’s great bar behind Piazza Navonna.

KH: Did Gregory try to learn some Italian? Did he embrace Italian culture?

FK: Gregory was steeped in classical cultures. He studied the Ancient Egyptians and could interpret and write hieroglyphs, and he was an expert on ancient Greek and Roman art. He navigated all art from everywhere and every period, from the roots to the future. We were always visiting museums and art galleries in Rome and New York, as well as artists in their studios. Art was an all-absorbing interest that bonded us.

As regards music, he was more interested in opera than in Thelonious Monk and other contemporary masters of jazz although he respected them highly. While drinking whiskey after a satisfying reading, Gregory was capable of singing Italian opera all night, remembering celebrated vocal parts and growing emotional like an old-fashioned Italian. Being completely toothless, he tended to sound like Popeye the Sailor Man when he sang.

He loved melodic music in general, in particular the compositions of Charles Ives. As for his command of Italian, I can only say that he made himself understood and got by, and sometimes had the ability to speak two languages simultaneously.

I discovered the short poem ‘Oh Roma’, scrawled in chalk, in Gregory’s unmistakable rushed handwriting, across a tattered poster attached to a wall near the ‘vinaio’. Copying the poem in my notebook, I showed it to Gregory, and it became the first track, ‘Americano/Italiano Rant’, on our LP Gregory Corso with the Music of Francis Kuipers:

‘Oh Roma’

Oh Roma

io molto tragico

io no homa, no papa, no mamma

Ah! No dente!

no bella donna

no dio

niente

solo io!

Oh Roma, io molto felicita’

my casa in tutto il mondo

io papa, 4 mamme, 4 bambini

I can buy dente grande come cocodrillo

ancora I got bella donna

signorina poesia

tutto io

ciao dio!

KH: I’ve been asking people I interview to try to give me an anecdote that they feel represents what Gregory meant to them. Do you have such a story?

FK: Gregory died twice! For reasons that I’ve forgotten, the major newspapers, as well as his favourite the New York Times, announced him dead three months before he was ready to go! [I was unable to verify this.—KH] Consumed by the pleasure of life, Gregory also had a life-long obsession with Death and he dreaded it. Reading about his demise, Gregory was mightily relieved and astonished. Not only was he still alive, but he had at least an extra three months of living in a terrestrial paradise!

The famous Japanese artist Hiro Yamagata had very generously rented the empty apartment next to Roger and Irvyne’s for him. Hiro also hired a Philippine male nurse to take care of him. All at once, Gregory had pristine white sheets and pillowcases, and he could happily watch baseball on TV with his friends in the greatest of comfort. Expertly looked after, not only was Gregory glad to discuss his own death notices and gratifying eulogies, but he also had time to put some neglected affairs in order.

On one on my last visits to Gregory, a few rows of wooden chairs were positioned in a semicircle around his bed. Amongst those present, there were Marianne Faithfull, Ira Cohen and the record producer Hal Willner, who was sitting by the head of the bed. Fussing about, the nurse pretended not to know about the half bottle of brandy that Gregory was hiding under his bedclothes. At Gregory’s urgent request, I’d gone down to the store to buy it.

Seated in the last row of chairs were an immobile, expressionless Japanese couple dressed in formal black raincoats. Mistakenly believing they might be associated with Hiro, at one stage I went over to thank them for their help. Not understanding a word of English, they gazed at me mutely. Irvyne later informed me they had nothing do with Hiro and that they’d probably most likely wandered in from the street. They’d climbed up the four steep floors to the apartment apparently attracted by the unusual energy there. She explained that strange things often happened around Gregory. Days later, at an informal event for him in the annex of a nearby church, I noticed the Japanese couple again, this time mysteriously lingering in the shadows.

Soon after, I was at Gregory’s bedside when his new-found daughter, Sheri, suddenly burst upon the scene, a tornado of vitality astonishing everyone, and arranged for him to move with her to Minnesota where he died.

When he was contented, Gregory Corso sometimes sang a jubilant little song: ‘Tra la lee, tra la lee, an artist’s life for me!’

Editor’s note: The 1988 recording mentioned in this interview, Gregory Corso with the Music of Francis Kuipers, carries the catalogue number Red Record 219

See also: ‘Book review #22: Corso: Ten Times a Poet’, April 15th, 2024; ‘Beat Meetings #1: Steven Taylor & Gregory Corso’, February 24th, 2023; ‘Beat Soundtrack #13: Kurt Hemmer’, March 15th, 2022

Never heard of this record before, which I discover is on the streamers. Beautifully recorded, sounds great, perfect accompaniment to reading this piece.

Wonderful remembrances of Corso by Francis K- Kurt interview marvelous- I was friends with Simon Vinkenoog. The poet of the people DICHTER VAN DE NEDERLAND- a fantastic mention of Jan Kremer author of Ik Jan Kremer - and of course Bobby Yarra in his own write a distinguished friend of Corso and biographer . FRISCO Tony