Interview #44: Joyce Johnson

Beat legend turns 90, talks music

ALTHOUGH SHE does not consider herself a Beat writer, Joyce Johnson, who turns 90 today, rubbed shoulders with that intense and alternative New York literary world of the mid-1950s, mingled with the novelists and poets who carried that radical tag, then gradually emerged as a published author and established talent in her own right.

She would spend two years, from 1957, as the girlfriend of Jack Kerouac. After that relationship ended she would complete a first novel, Come and Join the Dance, and see it published in 1962, before making her mark as memoirist, biographer and editor as well as an accomplished creator of fiction.

Born in 1935 and briefly a child star on stage, Joyce Glassman would attend Barnard College, the women-only sister institution to Columbia, from the age of 16. Through one of her lecturers, a university contemporary of Allen Ginsberg and Lucien Carr, she met various Beat figures including Carl Solomon and William Burroughs. She was also a friend of poet Elise Cowen, a sometime girlfriend of Ginsberg. The Kerouac connection would follow.

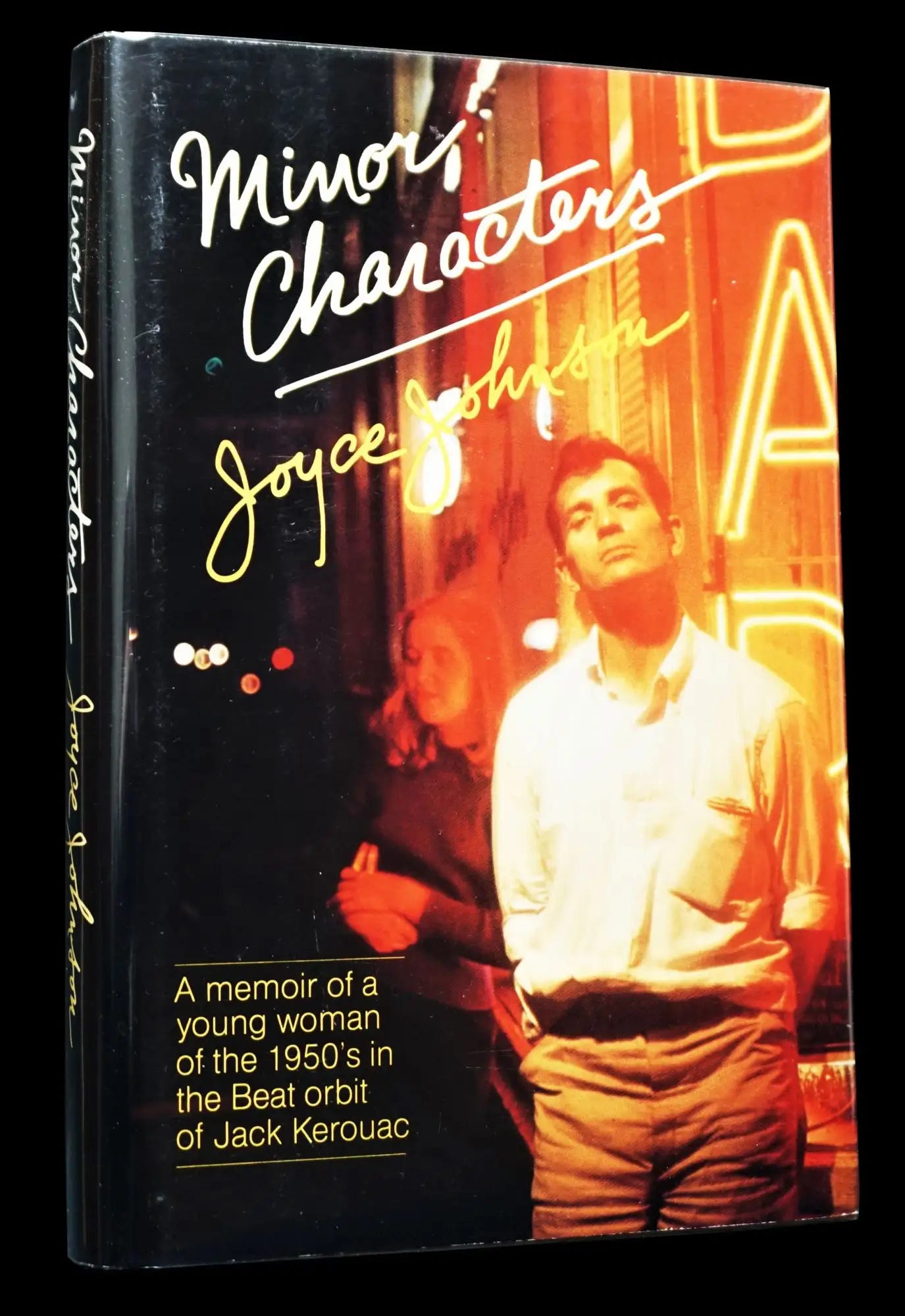

While romantically involved with Kerouac, his signature novel On the Road would be released to a rave New York Times review. His subsequent dalliance with fame and success had, within only a short time, a negative impact. He would eventually be consumed by alcoholism contributing to his early death. Joyce Johnson would much later produce Minor Characters, a prize-winning account of her time with him, in 1983.

Pictured above: Joyce Johnson, novelist and memoirist

Her other titles include an outstanding contemporary romance in Bad Connections (1978); In the Night Café (1990), a novel inspired by her first husband, the artist James Johnson, killed in a motorcycle accident the year after their wedding; Wide Open (2000), a personal history drawing on her correspondence with Kerouac; Missing Men (2005), a further memoir; and The Voice is All (2012), an important addition to the Kerouac biographical shelves.

With a major birthday imminent, Johnson, who has a writer son Daniel Pinchbeck by a second short marriage to another visual artist, agreed to talk to Rock and the Beat Generation Founding Editor SIMON WARNER about her musical allegiances and touched upon her associations with Kerouac and the Beat world…

______________________________________________________________________

Simon Warner: Do you have an interest in or passion for music?

Joyce Johnson: The music that I loved the most, I guess, was jazz. But I had a sort of unhappy history with music. When I was a child I had a mother who wanted to be the mother of a wunderkind and I had all this training in dance, training in all the arts. It didn’t work out. But I was in the theatre for a while.

And then, when that was over, my mother suddenly determined that I would have a career in music. I would be a composer and write musical comedies. I never felt I had a real talent for it and I was forced to add all that music training onto everything else I was being trained in…

SW: So you almost developed a resistance to music because of your mother’s ambitious behaviour…

JJ: The music that I liked as a teenager, my sort of my music, was folk music and I learnt how to play the guitar.

SW: Which folk artists caught your ear?

JJ: Well, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, those people. and I used to, for a couple of years, in fact over two years, when I was at high school, sneak down to Greenwich Village on Sundays. I told my mother I was doing homework with a friend and I would hang out in Washington Square with all the folk singers.

SW: Incredible…Did you see people like Seeger play in the Square? Who did you see?

JJ: No, no, there was this group of people…There was a guy named Erik Darling, who became known for a while. They were very passionate about it, they collected songs. There was also a lot of left-wing organising going on in the Square so I became acquainted with politics.

Pictured above: Folk artist Erik Darling, later a replacement for Pete Seeger in the Weavers

SW: At this stage perhaps you would be in your mid-teens, would you?

JJ: I started going down when I was 13, 14.

SW: So you were quite young to be doing that…

JJ: I was quite young to be doing that, yeah. I decided I wanted to be a bohemian (laughs).

SW: I guess in a sense you succeeded, didn’t you?

JJ: I did succeed at that, yes!

SW: You also mentioned, of course, that jazz was something that caught your attention.

JJ: Yes, I discovered jazz a little later on, you know, and, around the time that I met Kerouac, there was this wonderful, this legendary, jazz club on the Bowery called the Five Spot. You could go there, you know, have a beer for 25¢ and just hear all this great music.

SW: Can you remember any artists you saw during the period?

JJ: I once saw Billie Holiday. She wasn’t on the programme. She was under indictment for drugs or something. She stood up at her table and sang. That was sort of amazing.

SW: That sounds wonderful. And were there any instrumentalists you came across?

JJ: Ornette Coleman and, later on, Thelonious Monk played there. John Coltrane played there, too.

SW: So you saw some of the major figures of the 1950s and early 60s…Was there any sense that Kerouac was introducing you to these people or were you already familiar with them?

JJ: I was sort of familiar with them already. In fact, when he’d been away – he went to visit William Burroughs in Tangiers then he went on to Paris and thought he was going to stay on and on but he didn’t stay there very long. While he was away, I started hanging out at the Cedar Bar, then the Five Spot opened up. I introduced him to the Five Spot.

Pictured above: Jazz favourite Ornette Coleman

SW: Is it possible that you ever saw his jazz poetry appearances work with musician David Amram?

JJ: Yes, I did see that.

SW: That was supposed to be not such a great success either critically or for him personally. Do you recall those performances or the way they were received?

JJ: The gig at the Village Vanguard – David [Amram] wasn’t included in that – that was a sort of a disaster because he was really not a performer. He was a shy person basically. Possibly because he had this Franco-American upbringing when English was only his second language. He was shy in public so the only way he could overcome was to drink and drink and drink. So his performances there were rather a disaster.

SW: Yes, I believe so. But then as your relationship with Kerouac came to an end and you moved into the 1960s, did you keep up with the folk scene or jazz styles at all?

JJ: I continued with the jazz, particularly with jazz.

SW: Were there any later artists who you remember?

JJ: No…I still liked Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, Thelonious Monk, too.

SW: So did that popular music boom of the 1960s involving Dylan and the Beatles and others have any impact on you?

JJ: No, I wasn’t interested in that. I liked pure jazz.

SW: Was that kind of aesthetic judgement or did you feel commercial music was not your thing?

JJ: It just wasn’t my thing. It was a different generation.

SW: Although you are still young, weren’t you?

JJ: I was still young but I was older than the people who got involved with rock.

SW: So jazz and folk remained something in your life but those new popular styles didn’t appeal.

JJ: They weren’t my thing. I’d hear them and sort of enjoy them but I wasn’t into them.

SW: I was in touch with [Kerouac biographer] Ann Charters who helped me to get back in touch with you. You’re a good friend of Ann’s aren’t you?

JJ: Yes, yes, we’re really good friends

SW: She was married to Sam Charters. Did you him, too?

JJ: Yes, I knew him, too.

SW: And, of course, he was an important writer on the blues and other American folk traditions…

JJ: Yes.

SW: Could ask you a question or two about Jack Kerouac and the Beats? When did you last see Kerouac? Can you remember the last time you actually saw him?

JJ: Oh gosh… I do remember. In 1963, I think. I was married by then to my first husband James Johnson and Kerouac called out of the blue. He was with Lucien Carr. He wanted me to come on over. I said, ‘Jack I’m married.’ He said, ‘Bring your little husband.’

Pictured above: Joyce Johnson with Jack Kerouac, an image on the cover of her 1983 memoir Minor Characters

SW: And did you do so?

JJ: Yes, my husband consented to go (laughs). They were so far gone from heavy drinking. We didn’t stay very long. They were burning cigarettes on each other, which was rather alarming.

SW: So you last had contact with Jack around 1963…

JJ: Over the next few years, I’d occasionally get late-night phone calls from him.

SW: Did you get a great sense of sadness as the 1960s saw him decline in various ways?

JJ: It was tragic, I was very sad. I was very aware of his problems. Having done a lot of research and so on, I really think that all the injuries he sustained at football, the head injuries, really contributed to his deterioration, his moodiness. Starting from when he was a child and playing in Lowell, these sort of rubber caps instead of helmets, repeated blows on the head.

Then there was an incident, when I was still with him in 1958, when he was attacked outside a bar in the Village and beaten up. Guys were banging his head against the pavement and he really declined sharply after that. He began to have memory problems.

SW: It sounds as if head injuries were a key part in that process of decline.

JJ: Yes, cumulative injuries. He died young like the football players. Even judging by passages in his journals I quoted in The Voice is All, he was aware this might be an issue.

SW: And, of course, by the early 60s you were starting to publish yourself. Do you feel – obviously the Beats shaped your life on a personal level – do you think they affected your output artistically? I think of the novels, memoirs and so on I’ve read by you. Do you think the Beats influenced your own writing?

JJ: Well, I think writing letters to Jack changed my prose style in an important way. But I don’t really feel like a Beat writer. It’s too narrow a label for me and I do have other books, other interests. Bad Connections isn’t a Beat novel; my first novel, Come and Join the Dance, a book I wrote when I was quite young, was. But I started writing it before I even knew what Beat was.

SW: Seventy years on, what is your feeling about that Beat moment in the mid-1950s? Was it important? Was it a significant development in American letters?

JJ: It was very, very significant. It really changed the culture overnight almost. We were going through this period of repression similar to what is going on now. The McCarthy hearings and everything and all the prejudice against gay people and so on. Women were meant to have these really narrow lives. We got married right after college, disappeared into the suburbs, proceeded to have children. You didn’t have careers, you know what I mean.

They weren’t protesting yet but they were getting more and more fed up with it and I think Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and On the Road, they came along and blew the lid off and released all these pent-up feelings that people had under all that repression.

SW: Yes they were amazing works and it’s fascinating you were part of that history in a very close sense.

JJ: Yes, I feel privileged to have been part of that.

SW: But yes, as we’ve said, I know that your work spreads way beyond that quite limited Beat period. I also understand you’re going to turn 90 this coming Saturday.

JJ: That’s true.

SW: Is it a landmark you are excited about? Or does it not mean anything to you?

JJ: I’m not excited. It comes with so many problems, you know (laughs). I’m sort of astonished that I’ve reached this point!

SW: Well, we congratulate you on that notable birthday. I congratulate you on work produced over many decades and thank you for saying something about your own musical tastes for our readers. Much appreciated, Joyce.

Joyce Johnson a revelation - divine 90 years young. I wanna be Bohemian - dig the cool jazz - trip with Ann WALDMAN & David AmRam. - live in the Village and NorthBeach - stay @ Beat Hotel in Paris- Tangiers under Paul Bowles Sheltering Sky. Smoke hash with Brion Gysin to soundtrackof Drums of Jou Jouku. Drop acid with Ginzy & Neal Cassady @ Acid Test in San Francisco on the road to enlightenment. Frisco Tony

Wonderful. As with Carolyn Cassady I enjoyed Joyce's 'Minor Characters' immensely back in the day when I eventually found it.