Interview #7: Allan Jones

Leading British rock writer spent a professional life working for the UK's premier music magazines, but what were his reading habits away from the record player and the concert hall?

THEY CALL IT the golden age of rock journalism: that period from the early 1970s to the later 1980s when magazines – both the original newsprint inkies and the slicker glossies that followed – were hungrily consumed on both sides of the Atlantic by fans in their multi-millions.

And no one was more a standard bearer of that essential and electric moment than UK writer Allan Jones, a young and inexperienced recruit to the weekly London publication Melody Maker in 1974 who went on, over the next 40 years, to both report on and edit the key popular music stories of Anglo-America.

Jones, within a decade, was editor of MM, the great rival of New Musical Express, and, by the 1990s, had become founding force behind Uncut, the monthly magazine of music and film. Although both a MM and NME would eventually fall foul of the media reaper, the glossy mag continues to draw a substantial audience even though its original editor has long stepped back from that particular frey.

These matters came strongly to my mind over the last fortnight as I read Jones’ mercurial re-telling of those times when a rock’n’roll scribe was both guru to his readership and a deeply ambiguous figure to the stars he stalked: a target of ridicule at times, a recipient of contempt on occasions and, crucially, a significant powerbroker in a period when a bad press review could skewer a nascent career. So even pop’s most antagonistic egomaniacs were wise to tread carefully with their interrogators and their ever-present tape machines.

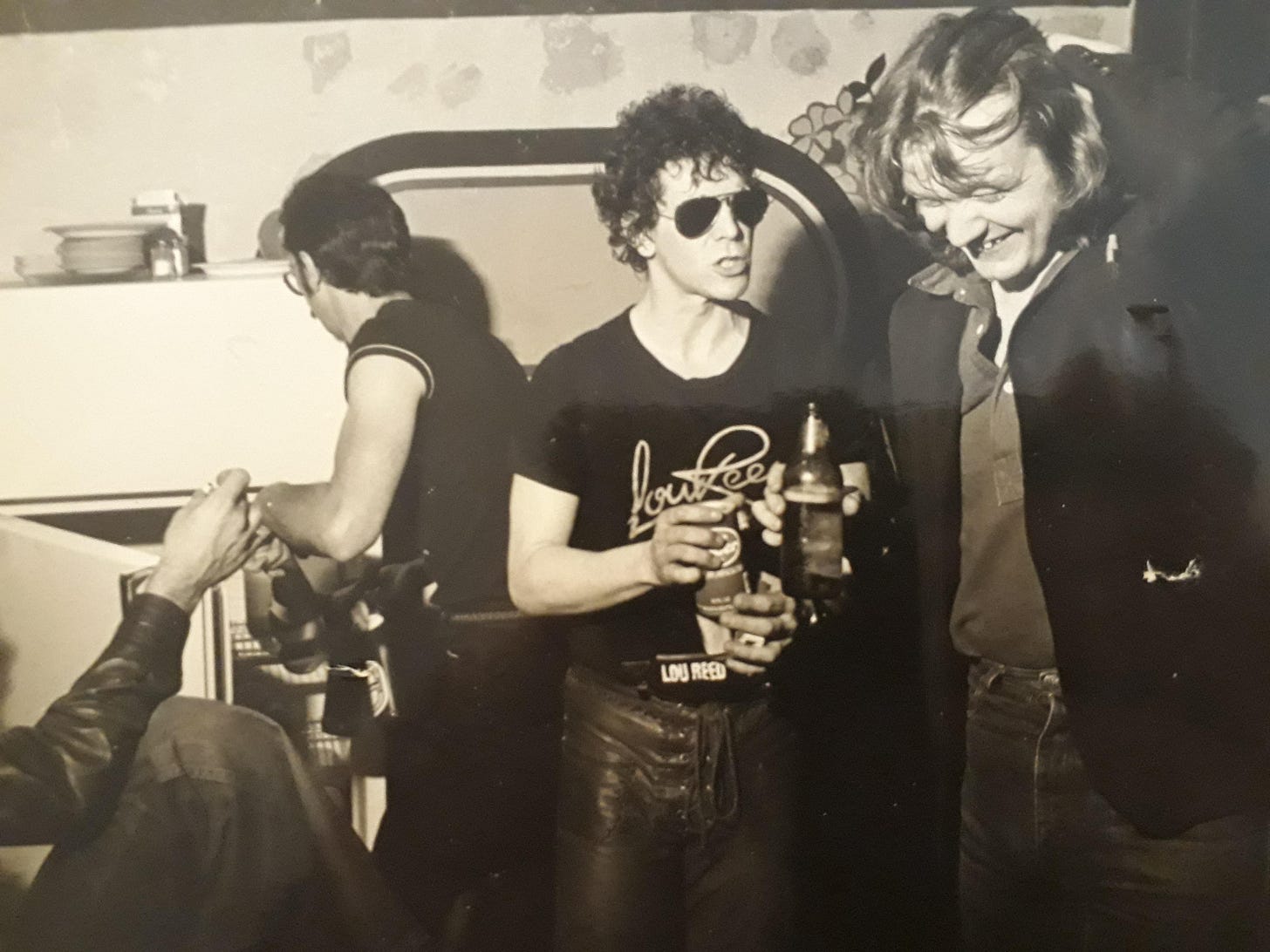

Pictured above: Reed and writer…the ex-Velvets frontman became a combative adversary to Allan Jones (right) on a number of occasions

These delicate and volatile relationships are beautifully distilled in the short, sharp recollections of Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down – a delicious and appropriate reference to Elvis Costello’s potent 1980 cover version as Jones’ slippery career ladder, at least in the very early days, is frequently greased with the temptations of strong liquor and cheap amphetamine.

The writing in this 2017 Bloomsbury collection is a sober reflection on experiences with some of the biggest stars of the period – Bowie and Van Morrison, Lou Reed and Michael Stipe, Rotten and Strummer, Patti Smith and indeed Costello himself, virtually all, as it happens, with a Beat interest or affiliation. But if the stories are now related with an air of distant reflection, the writing retains an uproarious, raucous, irreverent and very funny formula.

Pictured above: Jones’ memoir from 2017, soon to be followed by a second instalment

One thing that did occur to me was how much the radical writing of the 1950s and 1960s – from Kerouac and Burroughs to Tom Wolfe and Hunter S Thompson – fed into the new music journalism in the 1970s. I wondered, when I spoke to Jones recently, what impact those mid-century modernists had had on those young wordsmiths who became the critical commentators on that febrile span between Woodstock and the death of Kurt Cobain.

Did Jones see a synergy between what he listened to in his late teens, what he read during those years and the way he wrote about popular music from his early twenties? ‘To be honest, I'd never written anything apart from school essays and an art school thesis before joining Melody Maker. I'd had no previous ambition to be a writer, but I had read a lot.’

I wondered if the the Beat Generation had been on his reading list during his art studies at college in South Wales? ‘I knew the Beats, and like everyone else had read On the Road, some Burroughs, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso.’

He adds: ‘I spent the summer before I went to college tearing through everything I could find by Norman Mailer: Armies of the Night and Miami and the Siege of Chicago were later particularly important. I remember talking to Charlie Murray [Charles Shaar Murray, a star writer and friendly rival to Jones on New Musical Express] about how much we'd picked up from the latter, especially. I'd also read a lot of Tom Wolfe, so had a fair if rough idea what New Journalism was.’

Did the new wave of US music journalists impinge? ‘The only rock writing I knew was what I read in MM. I'd never heard of people like Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus, the American heavyweights. I did read Rolling Stone when I could get a copy, and was enthralled by Hunter Thompson's campaign trail reporting. Mostly what shaped whatever my writing became was mainly literature of one kind or another.’

Were there other novelists who helped to shape the Jones voice? ‘A lot of hard boiled US crime fiction, but also Evelyn Waugh and, if I was writing something hopefully comic, early Tom Sharpe was always an inspiration as was Tom Robbins (Another Roadside Attraction more than Even Cowgirls Get The Blues).’

But he adds a further significant name and inspiration. ‘If I had to pick one major influence though, it would be Elmore Leonard. Reading him for the first time was a revelation.’

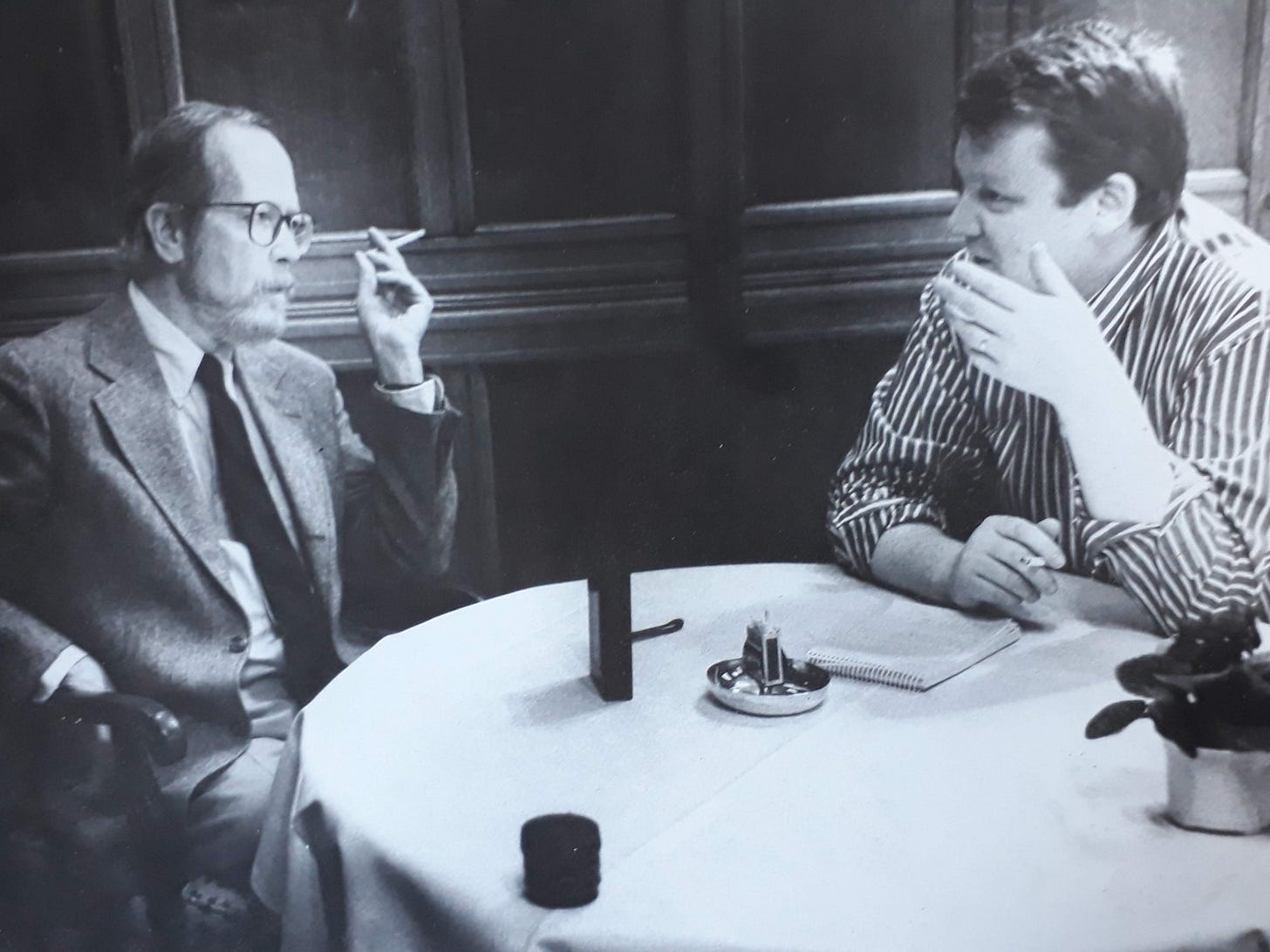

Pictured above: Celebrated crime thriller writer Elmore Leonard was both hero and interview subject to Allan Jones

Readers seeking some chunky slices of the seething rock frontline, as hippie became punk and then new wave, would do well to pick up a copy of Jones’ often rip roaring memoir. Better news still is that his publishers have now commissioned a second compilation, provisionally entitled It’s Too Late to Stop Now, with a 2023 release date already pencilled in the desk diary.