LATE LAST month, there were 60th anniversary trumpets blaring for the March on Washington, that magnificent, consciousness-shaking gathering in the US capital at which the charismatic words of Martin Luther King left a lasting imprint on the minds of the civilised West, probably indeed the globe.

On August 28th, 1963, the Atlanta-born Baptist minister led the way and seized the headlines of history. But there were others present, too, rallying the quarter million strong crowd, racially mixed, a striking symbol in itself of the age, the hopes, of integration in a nation still divided along colour lines and a separation, in many Southern states, supported by local legislation insisting that whites and blacks should exist apart from each other.

Bob Dylan, Shelton’s ‘choirboy/beatnik’, added his protest voice to the day, officially designated the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, so did his girlfriend, the soaringly sopranic Joan Baez, and there were further musical interludes – from Peter, Paul and Mary, operatic contralto Marian Anderson, gospel legend Mahalia Jackson and folk stalwart Odetta – lending a deep swell of empathetic harmony to the fierce words, gently communicated, by King himself.

But where, I wondered, as I read the Guardian’s commemorative report of that remarkable afternoon, sweltering with heat, simmering with possibility, were the representatives of the Beat Generation? Were the radical writing voices who had shaken up America in the previous 10 years present to add their own heft, show their solidarity with the campaign?

I wanted to find out if they had participated in some way. Did they comment? Did they write optimistic poems chanelling the positive energies of the moment? Did they pen essays or submit opinion pieces to the national press? Did they give interviews on radio or television about this groundbreaking phenomenon, staged in the full and resonant glare of the Lincoln Memorial?

Pictured above: Protestors in Washington, August 1963

I asked this question on the conversational stage of Facebook – particularly at the well-established group called ‘Our Allen’, a tribute to Ginsberg, his literary fraternity, friends and students – and hoped someone would know something. And they did. But not a great amount.

It tended to confirm my opinion-that-a-distance that while personal freedoms had been advocated by Beat members – they longed for the escape of the open road, they expressed sexual desires which stood well outside the norm of the day, they spoke in favour of drugs, shot arrows at the concept of censorship and sometimes attacked political convention – they didn’t seem to have the matter of race relations that high on their agenda for change.

When there was initially almost nothing forthcoming in response to my Facebook query, the UK-based independent researcher Jim Pennington – he has particular interests in the literature of the counterculture – suggested the apparent ‘stony silence’ on the matter spoke volumes.

Pennington remarked: ‘Very good question. The “stony silence” tells its own story. unless the Beats who did march were ones who did not write about their lives – just got on and lived it.’ He raised further points: ‘Into the mix I would ask did Joan Baez ever meet, say, Diane di Prima? And then I’d ask, where were Rexroth? Olson? Et alia. And now I’ll exit, dirging “We shall overlook, we shall overlook”.’ He also later proposed that ‘the crux of the freedom movement problem’ was that ‘it was spearheaded by a religious zeal and not socialist egalitarianism.’

But Steve Silberman, author of NeuroTribes, a bestselling history of autism, a former teaching assistant for Allen Ginsberg and the man who created and administers the ‘Our Allen’ list, felt there were actually glimmers of positive activity from the Beats from that crucial period that we should not discount or at least consider as part of our conversation.

Responding directly to Pennington, Silberman said: ‘When you quote the phrase “stony silence”, who are you quoting? Because I certainly think it's much more complicated than a stony silence. Kerouac was pretty naive about race, and thus elevated “the fellaheen” – really, indigenous people – in pretty classically racist noble savage ways, while insisting that “the future's in fellaheen”.’

He added: ‘Allen certainly helped promote the work of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, who was probably as close as you can get to a second-generation Beat who was black and very vocal about race relations. I agree that the Beats should have been more outspoken, but I don't think “stony silence”, wherever that phrase comes from, captures it.’

I even interjected on the thread myself: ‘I think this complicated territory is well worth further examination. Kerouac romanticised disinherited ethnic groups; Ginsberg used the term negro in a number of contexts (I think it’s Jonah Raskin who explores this in American Scream) before the term assumed taboo status; and Baraka had to sever his Beat allegiance to pursue the out and out separatist politics of a black radical.

‘The fact that the NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] was heavily backed by Jewish supporters makes the nexus of enquiry all the more tangled. A further intriguing twist is that Dylan (yet to meet Ginsberg, of course) was an active part of this Civil Rights conversation some years before the poet was unsuccessfully trying to persuade the singer to be a beacon of the anti-war project.’

Then the Facebook comments suddenly cast a true shaft of light, a reviving draft of insight, evidence of an individual who did regularly raise his banner above the still-dangerous parapets of the time and also actually, in person, attended the Great March, another more informal title the occasion has deservedly assumed.

Said US poet and union activist Chuck Pirtle: ‘Ed Sanders was there. Quoted in Kembrew McLeod, The Downtown Pop Underground: “I went down to DC with the Living Theater to be a part of the Great March on Washington. I brought along my Bell & Howell [movie camera], plus a satchel of the freshly published issues of my magazine”.’

There might be small arguments that Ed Sanders was not a true Beat, but so important a bridge was he between the literary scene of the 1950s and the counterculture that came into being in the 1960s that it would take a particularly inflexible view of this volatile era to exclude him. Probably only Ken Kesey played such an equally effective connecting role between the time of ‘Howl’ and On the Road and the anti-war energy that surged from Berkeley to Woodstock.

Sanders we might characterise as a Renaissance Man of the social revolution that rippled through the US from the ascent of Kennedy to the fall of Nixon. Not only was he a Greek graduate of New York University, a poet, publisher and political agitator, but also a central figure in the band who became one of the most effective critics of the systems of the establishment, using rock and folk, verse and satire, to lampoon and undermine the increasingly unstable certainties of the world’s mightiest superpower.

The Fugs, christened after the bowdlerised expletive Norman Mailer had been forced to utilise in his 1948 war novel The Naked and the Dead and launched in late 1964, became, via recordings, performances and publications, a spiky Lower East Side irritant for the establishment with Sanders joined by his most significant co-conspirator Tuli Kupferberg, already a veteran Beat poet in the Village of the 1950s. Though Kupferberg has now gone, the band continue to this day with their 13th studio long player Dancing in the Universe just out.

But to return to where we came in, Sanders, who had secured his Classics degree some months before his group were originally formed, would also show clear signs of his enthusiasm for an engagement with the tide of change by joining the Washington March that 1963 summer, a year before his graduation.

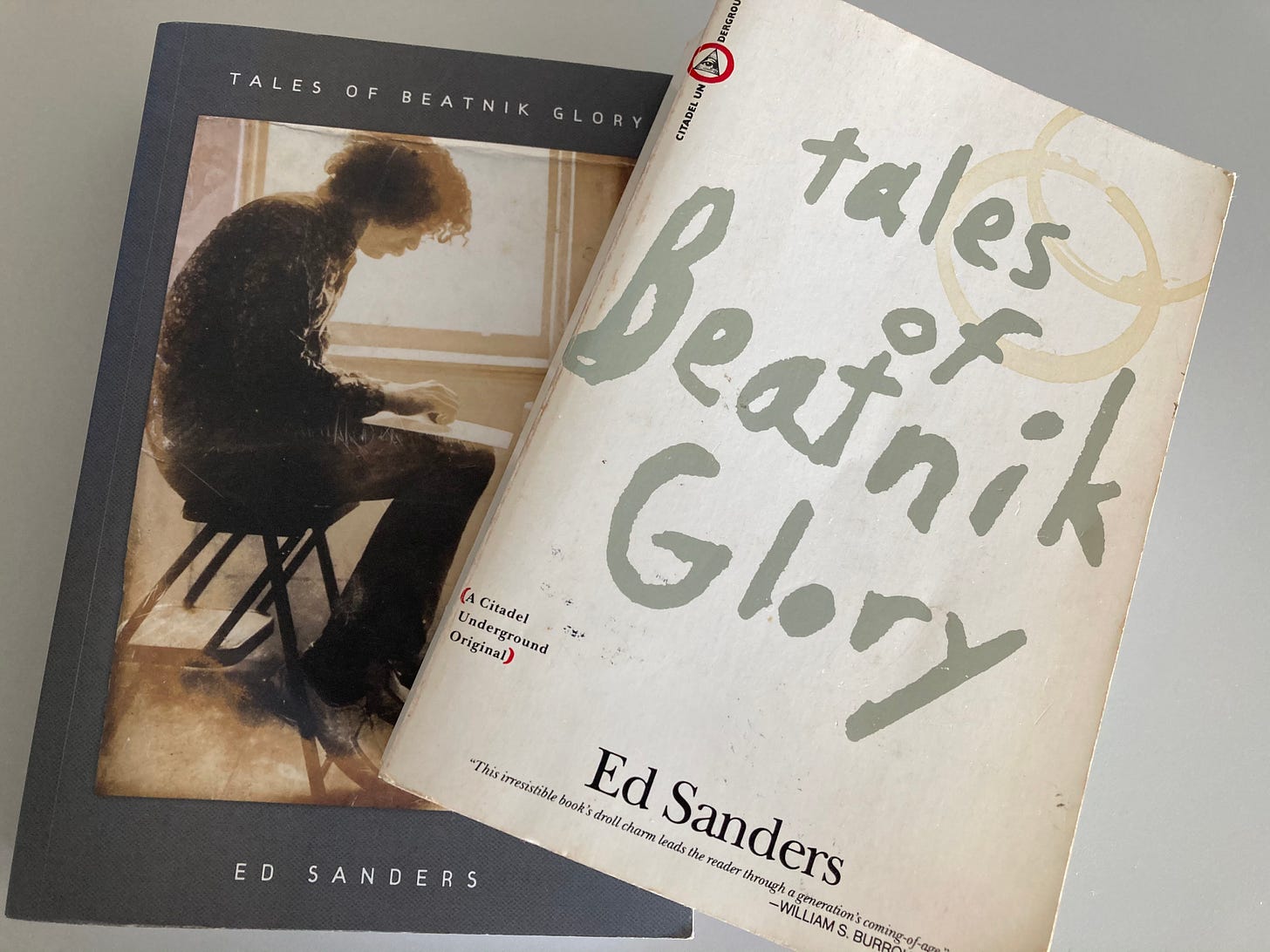

I’m further indebted to one-time Ginsberg Naropa student Chuck Pirtle’s extra contribution to the ‘Our Allen’ exchange because he very helpfully drew attention to a Sanders short story ‘I Have a Dream’ which forms a few pages in that eventually voluminous gathering of semi-autobiographical memoirs entitled Tales of Beatnik Glory, originally published in 1975 but emerging in expanded editions in the years that followed.

Pictured above: The original version of Ed Sanders’ Tales of Beatnik Glory

In fact, I first read Tales of Beatnik Glory when it initially appeared. It was a relatively slim but highly entertaining paperback collection providing rich delight for this university student trying to get to grips with the relatively small number of books released about the Beats and their fellow travellers at the time.

If we take the small liberty of working on the basis that ‘I Have a Dream’ is a close-to true representation of his Washington experiences six decades ago, then we also have an intriguing string of his acquaintances we might try to identify within the text.

I’d be delighted to establish who the other disguised cast members in the story – Rebecca Levy, Cynthia Pruitt, John Barrett, Louise Adams, Claudia Pred, Talbot the Great and Nelson Saite – were in real life. Maybe we can.

But these are pernickety details. As long as Sanders/Thomas was present to hear King and Dylan, Baez and Odette, then I had my key fragment of evidence a plausible Beat was there, a fizzing droplet in that seething ocean of groundbreaking actors, each sticking out a neck in a moment when it was really quite possible a police officer might just kneel on it.

And Sanders, maybe predictably, was more than just a passive observer of what went on. Something I didn’t know was that right wing protesters, no doubt with links to the Ku Klux Klan, were in the crowd as well and keen to stir up trouble.

Thomas, film camera in hand, was determined to make sure that this unwelcome infiltration was recorded before he became involved in physical fisticuffs with sinister figures he dubs ‘the ovenmen’ – a graphically grisly reference to the death factory of Auschwitz.

Our hero was ultimately bashed and arrested by the cops for his trouble, a clear sign that he had the courage not only of his convictions but also to be quite possibly convicted.

Pictured above: Later editions of Sanders’ fictionalised autobiography, including, on the left, an image of the author himself

Perhaps there is not a great deal more to add but I do invite my audience here to tell me if they think there were any other signs of Beat interaction with or reflection on this extraordinary interracial happening beyond the vivid and action-packed Sanders account.

Three final thoughts, however. In Washington, the great James Baldwin was denied a speaking berth as leading black novelist because of the fear that that he might stir up trouble with his straight talking, frequently controversial, takes on these tense and tortured topics.

Secondly, the March on Washington was desperate to be respectable and the characteristically anarchic, typically dishevelled beatnik strain could well have stained that core ambition. It’s worth remembering that Dylan, perhaps already the archetypal apprentice Beat himself, gave a drunken acceptance speech some months later, as he received the Tom Paine Award for his efforts on the Civil Rights front, shocking an audience of die-hard liberals when he said:

‘I want to accept it in my name but I’m not really accepting it in my name and I’m not accepting it in any kind of group’s name, any Negro group or any other kind of group. There are Negroes – I was on the march on Washington up on the platform and I looked around at all the Negroes there and I didn’t see any Negroes that looked like none of my friends. My friends don’t wear suits. My friends don’t have to wear suits.’

But finally, let me quote the very final paragraph of Sanders’ short story:

‘Sam Thomas was wadded up and stuffed into the paddy wagon. Before they shut the door came another startling vision. It was the hovering face of secret policeman J. Edgar Hoover, spread across the sky like a dead carp at the mouth of a sewer. Sam saw a time of crazed peril for America. There was a crackle of insane electricity in the brains of madmen, and planes swooping low over villages with fires that would not stop’.

Chilling, terrifying, prescient stuff from the novice poet and rocker-to-be who could not resist being there, locking horns for the cause then cocking his thumb like a benign trigger, looking for a freedom ride at the crossroads of America, hitchhiking into the flaming horizon of a near apocalyptic future.

See also: ‘Beat Meetings #4: Gottfried Distl and Ed Sanders’, April 23rd, 2023

I would argue that Ed Sanders was a pioneering Beat, and as you note, a true Renaissance Man. I was (maybe still am?) fortunate enough to get to know him a little by moving to Woodstock. In true Sanders fashion, he wouldn't be interviewed for my book on the New York City music scene, claiming he had 50 documentary requests alone in front of him and only limited time left to complete his life work - to which I could not argue - but he spiritedly rallied round the cause of local schools when I called him on that issue instead and we developed a passing friendship that way instead. There is nothing that quite screams "I must be living in Woodstock" like shopping at the local health food store alongside the highly distinct Sanders. I believe there is a Fugs concert of some sort taking place almost as we speak, so his determination to keep on moving remains admirable. As much as any of the Beats, I believe he has stayed the course, true to his politics and his art, from Day 1 to today. I t doesn't surprise me that he is one of the only Beats you can confirm was at the March on Washington. Cheers!