New Kerouac sleeve notes #2: Pat Thomas

A prominent historian of the US counterculture shares exclusive access, via Rock and the Beat Generation, to his latest Beat album liners with Blues and Haikus the next up

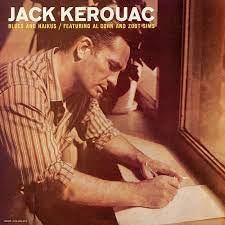

WHEN REAL Gone Records decided to release new vinyl editions of Jack Kerouac’s first two long players, in the novelist’s Centenary year, they commissioned long-established music journalist and reissue specialist Pat Thomas to pen a fresh set of sleeve notes. But the label made a last-minute decision not to include text with the releases.

The LA-based Thomas has now allowed access here to his two previously unpublished essays. Here he considers the second recording Blues and Haikus, featuring saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims laid down in 1958, released in 1959 and to be re-released next month.

Look out also, in the pages of R&BG, for his planned commentary on Poetry for the Beat Generation by Kerouac and pianist Steve Allen, recorded in 1958, originally released in 1959 and also to be re-emerge next month.

Jack Kerouac featuring Al Cohn and Zoot Sims – Blues and Haikus

‘Poems from the unpublished “Book of Blues”’

By Pat Thomas

Jack Kerouac’s Blues and Haikus featuring Al Cohn and Zoot Sims was recorded in Spring 1958 (after Jack’s album with Steve Allen) – and released by Hanover Records in October 1959. The four selections were written and read by Kerouac accompanied by the two saxophonists who composed the music. Cohn also makes his recording debut as a piano player on this LP – yeah, that’s him on ‘Hard Hearted Old Farmer’ and ‘The Last Hotel & Some of Dharma’. Dig how occasionally Jack even moves from poet to singer – a touch of Sinatra, maybe?

As he had with the previous album Poetry for The Beat Generation, Bob Thiele produced Blues and Haikus, greenlighting Jack’s choice of accompanists, despite being worried that two tenor saxes could overpower Kerouac’s voice. Also, it’s worth noting that Thiele and Steve Allen co-founded Hanover Records so they could release these two Kerouac albums!

Of the two Hanover albums, this one is a bit more musical, yet retains that ‘first thought, best thought’ vibe – sometimes with laughter and a rustling of papers. Kerouac is audibly more comfortable this time around. It’s been told many times, but for Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, this was just another gig – they weren’t particularly taken with Kerouac. He was depressed, they didn’t want to stick around after the session and hang out, but as Bob Thiele pointed out, these were hardened session men – who wouldn’t have stuck around after a Benny Goodman or Duke Ellington date either! When the work was done, it was bar time.

Poetry for the Beat Generation contained 14 individual recordings ranging from 30 seconds to seven minutes with many of them just a minute or three - Blues and Haikus had 14-minutes of San Francisco Blues (choruses 1-23) which didn’t get published until the early 1990s, plus two minutes of ‘Hard Hearted Old Farmer’ and a four minute ‘The Last Hotel’ – both of which haven’t made it to book form that I’m aware. The other entry was 10 minutes of ‘American Haikus’ – from Book of Haikus – portions of which were included in 1971’s Scattered Poems, published by City Lights.

Al Cohn was a saxophonist, arranger, and composer – first known to the public for his membership in clarinetist Woody Herman's band and over time for his musical partnership with Zoot Sims. Cohn's work as an arranger was popular – including Broadway productions like Sophisticated Ladies and his own compositions were recorded by other artists such as Maynard Ferguson and Gerry Mulligan. Interestingly, Cohn appeared on stage with Elvis Presley in June 1972, at Madison Square Garden.

John ‘Zoot’ Sims was also saxophonist, playing mainly tenor but also alto and soprano – first known as part of the ‘Four Brothers’ sax section of Woody Herman's big band, then breaking out on his own – often teaming with fellow sax players Gerry Mulligan and Al Cohn. Sims played a solo on Phoebe Snow's 1974 hit song ‘Poetry Man’ and he's heard on Laura Nyro's classic album Eli and the Thirteenth Confession.

As I listen to Kerouac’s voice interplaying with these saxophones and piano – I’m reminded why he has captured the imagination of so many musicians – because it’s 20th Century ‘Wild West’ Americana, it’s sex and drugs and music, it’s a life without rules or restrictions. In February 2017, I was lucky enough to chat with singer/songwriter Graham Parker about this very topic.

‘I picked up this book in a little bookstore, a paperback of Jack Kerouac’s Lonesome Traveler…It wasn’t like On the Road, which he wrote as a novel like The Town and the City. I think it was maybe some publishing idea… but anyway, to me, it flowed beautifully, and I just loved to romantic idea, the railway earth, and traveling somewhere with very little, getting jobs in exotic places, like working on the trains and cooking for himself with a little [hotplate] in a tiny [apartment] somewhere in San Francisco. I thought it was just a marvelous idea and because I was, by then, a certified freak, a hippie, and I’d left home by the time I was just about eighteen, I went to a place called Guernsey in the Channel Islands, spent some time there, hung out with freaks, and listened to music of the times.

‘Then I went back to England, did various jobs and then I was only about twenty or twenty-one when I went off to Paris. Got on the ferry and went to Paris with the backpack on, the guitar, got into playing and fingerpicking. I was really trying to learn to play properly, which I’d never actually done before despite the interested. So, I was developing that kind of artistic side of myself, and it was starting to look like something, like it might go somewhere someday, you know. I got my first record deal when I was twenty-five, I suppose, in 1975. Kerouac’s book was very much part of that for me. I just felt that whole Lonesome Traveler thing. Hitchhiking to the ferry I took from Paris. I don’t know whether I had a frying pan with me, but I might have done. [laughs] It was just fantastic.

‘What I was doing is going to Paris; I stayed there for a while – very much with no money. Very, very little money – I’d just saved little bits, and found my way through Spain. It was just interesting going south of France by hitchhiking, maybe taking a train when I could afford it. I’d hitchhike and find myself in the middle of nowhere because the guy had to turn off somewhere else and then point off south to Spain, that way, and I’d sleep on the edge of the road. I woke up once on what turned out to be a triangle in the middle of a highway. It was empty at night, pitch black, and I just found some grass, put my sleeping bag there, woke up covered in snails to the sound of trucks roaring right next to me. So, I did all those kinds of things and then I ended up in Morocco. Talk about the fellaheen, Beatnik world. There it was: Morocco. I’d known that Burroughs had gone, and it was part of the Marrakesh Express, you go there to smoke a lot of dope, basically. The idea of sitting with old blokes, Moroccans, and smoking with a clay pipe, you know? Very, very cheap pot. I didn’t have much money there, and then when I ran out people said, ‘Go to Gibraltar’, which was a short ferry ride. I went there, found myself a place to crash, found a room full of bunks, which some slumlord was selling for a few shillings, and I got a job on the decks. So, it was very much a part of that, very much living the Kerouac dream, in a way. It was influential in that respect, and I was writing some songs that were a bit hippie, you know, they weren’t quite right. They were a bit flowery and all that stuff, but I could tell that some of the melodic structures were good. It was very much that Lonesome Traveler thing, on the road, so I think it must have had quite an influence in that respect.’

I assume you’re talking early 70s when you’re cruising through Paris and Morocco?

‘Yes, well, basically. I know it was ‘71, I believe, or ‘72 even – don’t quote me. When I was there, there were these riots going on, marches, Angela Davis. I think that might have been ‘71 or ‘72 because years later I looked it up trying to figure out when did I do all these things… I did not keep notes really well. Guernsey, that was about ‘68. I was just turning eighteen maybe when I’d just left home. I don’t know whether I’d read Kerouac’s book then. It might have been before the next trip. I came back to England, and I think that’s when I probably found it, probably ‘70 or something in a bookstore somewhere when that was actually released. These things get hazy but we’re talking about a period from about ‘68 up to ‘73 perhaps when I was doing that, and then I came back to England and stayed at my parents’ house and said, ‘That’s it for traveling, I’m not going to do it again until I get paid’, which was an incredibly rash statement but what it meant was is that now you’re going to write songs, you’re going to get a record deal, and you’re going to be famous so when you travel you’re going to be getting paid to do it. So, somehow it worked, strangely. [Laughs] That’s the time period we’re talking about.’

I want to run this by you, years ago I interviewed Ginsberg and we were talking about how there’s a direct lineage from the Beats to the hippies to the punks, right? That it’s a countercultural thing and one of the things that I found interesting is when you and Elvis Costello, Joe Jackson, the Clash – when you guys all sort of exploded on the scene within a year or two of each other, it was interesting to find out many years later that many of you had been, in fact, hippies.

‘Absolutely, yeah, I was primo freak. I did whole acid trips and was healthy to someone, probably – mentally healthy, anyway – but managed to come out the other end of it. But absolutely – I had the hair…that’s it. The travel thing was part of the freak idea and of course, there it was, we knew where the predecessors were with the Beats. They experimented with drugs, they got into meditation, they got their Eastern philosophies, they were doing that in, what, the 50s? Yeah. There you go. Totally different from my life in the 50s growing up. I was born in 1950. I was born in London but was only there for four years and grew up in the suburbs, so it was just a fascinating idea. It was nonconformity. That’s what being a hippie was, it was a nonconformist and you gravitated toward an interest in Buddhism, and I’d got Jack Kerouac. There you go. You gravitated toward those things. They just seemed to be part of that freak culture. I don’t think there were many freaks that didn’t know William Burroughs or Jack Kerouac at least by name, on some level, or had read some of their works. Those books were circulated, and it was very much that that precedent was there, and we just fell into our own version of it, which came from the Beatles, and suddenly Sgt. Pepper and all those kinds of things...Jimi Hendrix, and the psychedelic thing. So yeah, definitely, the hippie thing was very much part of me before I reinvented myself once again and cut my hair brutally short and found myself singing music that was very un-hippie, in a way, my first records. Nobody seemed to know, they wouldn’t have guessed the lineage.’

To me, there’s always been a very American influence in your music – you know, R&B, soul. Let’s talk about the Americanism, jazz, and soul in your songwriting.

‘Well, before even the Stones or the Beatles came along, we’d have the [radio console] this giant, beautiful wooden thing and you’d hear, even then, most of it was American music in the shape of Doris Day and Bing Crosby – classic songs like that…

‘The Stones album, for instance, the very first one, it’s a history lesson. I was probably aware of a bit of Southern music and a bit of blues because in England, blues artists were revered, even in the 60s. Even before the Stones and the Beatles, I had people who were friends of mine, art college kids, and I hung out with them, and they had a Sonny Boy Williamson record. It was like something from another planet. It was really the Stones where you looked at the credits on the Stones album and there’s all these writers, “Who is this C. Berry guy? Who’s he?”

‘The Beatles were doing “Please Mr. Postman”, “Twist and Shout”, I mean, these guys didn’t pull it out of nowhere! They had the same precedence. They were going to the Liverpool docks; the sailors were coming in with 45 singles of these acts and Mick Jagger was writing to Chess Records sending checks or money orders and getting records. [Later], we had more record stores, our generation, so we could go, and you’d just look through the racks – “Can I afford this Lightnin’ Hopkins record?” In the suburbs, even when I was sixteen, you could go and see Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee in some cobble street town nearby, very nearby where I grew up in the county of Surrey. If you’d go to Guildford or somewhere like that or Woking, you’d see these kinds of acts. I mean, the British Blues bands came along, which I was very, very into – obsessed with – Peter Green, Chicken Shack, all those acts, John Mayall. That became a very fashionable thing, so I hadn’t got into the freak music until I left home, and everybody was listening to this incomprehensible music. We’d figured out that you’ve got to take this psychedelic stuff to understand it and you did and suddenly you became… “Oh, OK, this is the stuff.” I couldn’t listen to 12-bar blues or soul music for years. I couldn’t stomach it! It sounded unbearably straight. I did that whole trip to Morocco, came back to England and something kicked it. I’d hear something like the Four Tops on the radio or “Summertime Blues” by Eddie Cochran… I’d hear it on the radio and suddenly it got right to me again and I started sliding away from the hippie stuff, but I’m still into a very eclectic mix...but it was more like I’d put on a Staples Singers album, that would be more like it. My inspiration came from those days of the Beatles and The Stones all those other great beat groups that magically appeared, and they were very affiliated with American music, and soul music.’

One of the things that’s great about Kerouac’s writing, as you know, is that he captures the beautiful simplicity of having a breakfast in an American diner. The bacon, the eggs, obviously the road...so let’s talk about the first couple of times you came to America because you were suddenly seeing all these things that you had thought about. What was that like for you?

‘Yeah, well, as I said, by then I was a musician, a professional, so it was an airplane, a rental van with the band in the back of the station wagon touring and we stopped at all those places. I suppose - I can’t remember distinctly, but I’m sure I thought, “This is it, the Railroad Earth”, and we’d be in some very Beat places. I would even remember traveling across some part of America and it was like forest, it was beautiful, and there was some kind of restaurant that looked like a shack. We went in there and there were basically benches. There were American Indians, what they call Native Americans. Native Americans were in there eating and they were eating Mexican food, it was tacos. I was introduced to that kind of food, and I remember afterward I was at a gig in New York, the Bottom Line, going out with Martin, the guitarist for The Rumor, and we found some diner that just seemed to be a straight strip of chairs and you sat at the counter and there’s these hotplates and they’re whipping out the egg. I had one of the best burgers I’ve ever had –maybe because I was stoned or I’d done the gig and it was one of those munchies things at three in the morning – and it was full of cab drivers. There were all these Beat cab drivers and there I would definitely have remembered Kerouac and thought, “Wow, I’m doing it - but I’m getting paid to do it!” [laughs]’

I’ve long thought of Graham Parker’s music as the missing link between Van Morrison and Elvis Costello – but I also foolishly thought that hiding behind those dark glasses was a man, who like Van might be a bit of a curmudgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth! My conversation with Parker flowed easily and since we were both Kerouac aficionados – we hit it off right away.

While many of you are familiar with Parker’s inspired singing/songwriting (both with and without the Rumour) – what you may not know is that Parker has recorded several of Kerouac’s works – spoken word recordings in collaboration with Jack’s buddy, musician David Amram.

Parker reads from Jack Kerouac's unpublished journals 1949-50 on the Japanese version of the Kerouac tribute CD Kicks Joy Darkness. And on the Jack Kerouac ROMnibus (CD-ROM), Graham reads passages of Dharma Bums & Visions of Cody, accompanied by David Amram and there is also an audiocassette of the complete Visions of Cody book with original music by Amram.

PT

From the West Coast of America, April 2022

Author of Material Wealth: Mining the Personal Archive of Allen Ginsberg (forthcoming, 2023) and a contributor to Kerouac on Record: A Literary Soundtrack (2018)

See also: ‘New Kerouac sleeve notes #1: Pat Thomas’, published November 6th, 2022

Thoroughly enjoyable and most edifying essay. Thoroughly enjoyed both Pat's discussion of

the Blues and Haiku's album and the conversation with Graham Parker. It was a wonderful, down to earth discussion of how's we're influenced and inspired by what we encounter in our travels, and Kerouac's vital invitation for so many to head out after a good breakfast of bacon and eggs. Was thinking about this very topic as I ate at Mel's diner earlier today before jumping in my car and heading down the California coast. Nice read Pat!