Paperback reader: Tracking Dylan’s Road trip

Bob's first bite of Beat classic – but when?

WHEN DID you first read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road? When, for that matter, did I initially consume the most celebrated of all Beat novels? And when did Bob Dylan, himself a long-time Kerouac adherent of course, first devour the ever-compelling pages of that thrillingly original adventure of the American highway?

I will leave you to consider the opening question and come up with an answer in your own time. As for me, I’m having a little difficulty. Why? Well, I actually delved into other books from the Kerouac canon – including The Town and the City and Vanity of Duluoz plus Ann Charters’ ground-breaking biography – around 1973 and 1974 before I eventually picked up On the Road. That might have been as late as 1975, now a somewhat surprising half a century ago.

As for Dylan, I’ve been attempting to pinpoint a possible time for his initiation into the Kerouac classic. I was wondering about this recently as I was enjoying Elijah Wald’s fine book Dylan Goes Electric!, a smart and approachable history of the singer’s early years leading to his dramatic amplified move at Newport in 1965, an account identified as a key inspiration for the widely-acclaimed movie A Complete Unknown.

Wald doesn’t tarry over such arcane On the Road detail in his own survey, but he does talk about the personal treks the singer undertook in 1960 and it left me musing which pieces of literature might have most likely fuelled Dylan’s young wanderlust and cultivated the idea that to journey was to shape a distinct and independent artistry, autonomously develop a creative persona he could own.

Pictured above: A Kerouac Centenary edition of On the Road and Dylan’s own Chronicles

I’ve been talking to various individuals who certainly know something about this topic but let us say this from the outset: just as you might be a bit unsure as to when you cracked open this celebrated paperback – like me! – it could be the case that even Dylan is not certain when this happened for him. But, setting that issue to one side, we will give the quest a go.

First, a few temporal and cultural markers. On the Road was published in the US in September 1957 in a hardback edition. The paperback version appeared a year later. I have some reasonable doubts that this landmark Kerouac tale would have been that easily available in the local bookstore to a teenager like Dylan in the backwoods of beyond.

I almost wonder if the controversy raised by Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and the court case which followed in San Francisco, just the next month after On the Road emerged in print, would have disadvantaged general distribution of any books with a Beat taint, especially when conformity was the necessary fashion of the time.

The obscenity trial addressing the status of the poem generated national headlines and marked this rising group of writers as a disruptive challenge to the status quo, not a great selling point in a provincial high street at the time, even if the sitting judge would eventually rule in favour of the poem under legal scrutiny.

Bob Dylan left his boyhood town of Hibbing for the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis in the early fall of 1959, a whole two years after the original appearance of the Kerouac text. He was, however, a rare attender on his college course during that first semester and soon he was spending the bulk of his time in Dinkytown, the bohemian neighbourhood of the city of Minneapolis, a scaled down Midwest version of Greenwich Village. It is here, we are led to believe, that he first encountered Beat poets, at least on the page.

Richard Williams, Dylan biographer in the shape of 1992’s A Man Called Alias, explains: ‘The best thing about Minneapolis was the access to a ready-made coffee-house social life, most of which was centred on a district called Dinkytown. This is where the local Bohemians congregated. They were the last flowering of the Beat Generation, the sort of people still fired by Jack Kerouac and Lenny Bruce, Zen and Existentialism…’

Another noted biographer Robert Shelton directly quoted Dylan on that bustling local scene in his 1986 portrait No Direction Home: ‘There was unrest…frustration…like the calm before a hurricane…There were always a lot of poems recited…Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso and Ferlinghetti…I got in at the tail end…and it was magic…every day was like Sunday.’

Pictured above: A 1972 Penguin version of On the Road and an illustrated Dylan biography from 2005

Yet it seems most likely that, in those closing months of the 1950s, he was exposed mainly to poetry volumes like Howl and Other Poems, Gasoline and A Coney Island of the Mind and just possibly the newly-minted Kerouac first edition of Mexico City Blues, only released by Grove Press in November 1959, a verse collection to which Dylan appears to have taken a particular shine.

But had he also devoured On the Road before that decade was out? The singer is reported at his own official website stating: ‘I maybe read On the Road in 1959. It changed my life like you changed everybody else’s’, a detail kindly brought to my attention by that well-known Canadian Beat commentator and counterculture raconteur Brian Hassett.

Yet Steve Turner, respected British popular culture historian and Kerouac biographer, thinks that is probably not the case and that Dylan is mistaken in his date claim. On that central question of when the singer read the novel, Turner remarks: ‘My guess is Minneapolis, early 1960, based on things he has said and also conversations with the guy who gave him Kerouac and Guthrie books. Dylan is on record saying 1959 but it doesn't fit the chronology of his friend who was on a kibbutz in Israel in 1959.’

That friend, who carried the nickname Diamond Dave and to whom Turner spoke when he was researching Hydrogen Jukebox, his forthcoming history of popular music and the Beats, ‘couldn't recall exactly what he'd given him but Dylan has said he gave him Mexico City Blues and Bound for Glory.’

Based on that important fragment from Turner’s first-hand research, perhaps the singer did not handle and then read the poem cycle in ‘242 Choruses’ that was Mexico City Blues or even the Guthrie book until the start of 1960 and maybe not On the Road itself until even after that.

But what about another recognised expert historian, Clinton Heylin, one of the great transatlantic Dylanologists? The UK-based author with multiple volumes covering the life and work of the singer-songwriter to his name steered me towards his own The Double Life of Bob Dylan, Vol. 1 1941-1966: A Restless, Hungry Feeling (2021).

With reference specifically to Mexico City Blues, Heylin’s account reports that in 1975 Dylan told Ginsberg at Kerouac’s Lowell graveside, ‘My good friend Dave Whitaker gave me a copy of this book … in Minneapolis in 1959 … [and] it blew a hole in my mind.’

Steve Turner’s previously-quoted evidence would dispute Dylan’s claim that Mexico City Blues makes an appearance in his life as early as 1959. And we have a further point of correlation: the David Whittaker mentioned by Dylan is the very same Diamond Dave of Turner’s acquaintance.

Nor do we have any mention at all in this context of On the Road, so it does start to appear highly likely that Kerouac’s most famous text had not actually arrived on the Dylan bookshelf until after 1960 had dawned.

We know that, by May of that year, Dylan has fully unhooked himself from the university life and soon after sets out on a trip West. Wald reveals that, in the summer of that year, he heads to Denver; a little later in the autumn he travels to Chicago and Madison, Wisconsin.

Turner’s investigation suggests that Dylan might well have been inspired to journey having read Bound for Glory, Guthrie’s autobiographical novel which had been available since the 1940s, and also the significantly more recent On the Road, but not until the curtain had risen on the new decade. Perhaps digesting a double dose of picaresque fiction triggered the singer’s solo trips into the American interior, imitation as the sincerest form of flattery.

Much later Dylan put some further flesh on those speculative bones, as noted UK independent Beat scholar Dave Moore reminded me. In his autobiography Chronicles: Volume One, which came out in 2004, the performer returned to matters Kerouac when he stated:

‘On the Road had been like a bible for me. I loved the breathless, dynamic bop poetry phrases that flowed from Jack’s pen … I fell into that atmosphere of everything Kerouac was saying about the world being completely mad, and the only people for him that were interesting were the mad people, the mad ones, the ones who were mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn, all of those mad ones, and I felt like I fit right into that bunch.’

But Dylan added when interviewed for the 2005 Martin Scorsese documentary No Direction Home (which shares the Shelton biography book title): ‘One guy gave me a book that Woody Guthrie wrote called Bound for Glory, and I read it. I identified with that book more than I even did with On the Road.’

In January 1961, his lone excursions of the previous months completed, Bob Dylan decisively left behind his unfulfilling campus life and the relative parochialism of Minnesota and headed for the bitter cold of a New York City winter with who-knows-what in mind beyond the determination to make contact with an ailing hospital patient, folk legend Guthrie himself, bed-bound in a New Jersey ward.

Pictured above: A lavish volume celebrating the 2012 movie of On the Road and a pensive singer on the cover of 1999’s photographic collection Early Dylan

And, in Chronicles once more, as his circumstances dramatically alter, he expresses an important sea change in his attitude to On the Road. The love affair with Kerouac’s signature text was not at an end – he still felt a passion for the writer’s voice, as a way of talking on the page – but Dylan’s approach to the subject matter had shifted. In short, Dean, the star of the piece, based on Neal Cassady, had lost his allure.

Dylan, again in Chronicles, tells us: ‘Within the first few months that I was in New York I’d lost my interest in the “hungry for kicks” hipster vision that Kerouac illustrates so well in his book […]. That book had been like a bible for me. Not anymore, though. I still loved the breathless, dynamic bop poetry phrases that flowed from Jack’s pen, but now, that character Moriarty seemed out of place, purposeless – seemed like a character who inspired idiocy. He goes through life bumping and grinding with a bull on top of him.’

It may be significant that, while the singer meets and befriends Guthrie, he never, as far as we are aware, goes searching for Kerouac. Ginsberg, whom he first runs into face-to-face, in the Eighth Street Bookshop the day after Christmas of 1963, could surely have arranged for the singer to meet the novelist, if he had wanted to. Perhaps this was one hero he had resolved never to meet.

But to turn the clock forward a little, by 1964 Dylan was a high profile figure, able to connect with the Beatles that summer on equal terms at a Manhattan hotel and turn them on to marijuana. In the meantime, he had established himself as the leading folk player and star soloist of the day and had already undertaken a new US trek, joined by three male friends, on a further journey West by car in the spring of that same year.

To what extent did Dylan’s itchy feet inclinations, remnants surely of his passion for the writings of Guthrie and Kerouac, survive as the commercial behemoth of the music industry drove him forward from the middle of the decade? After the electrification controversy of Newport in 1965, stung by the negative reception at the festival and subsequently, he endured a somewhat unhappy concert tour with his new collaborators, members of the group the Hawks.

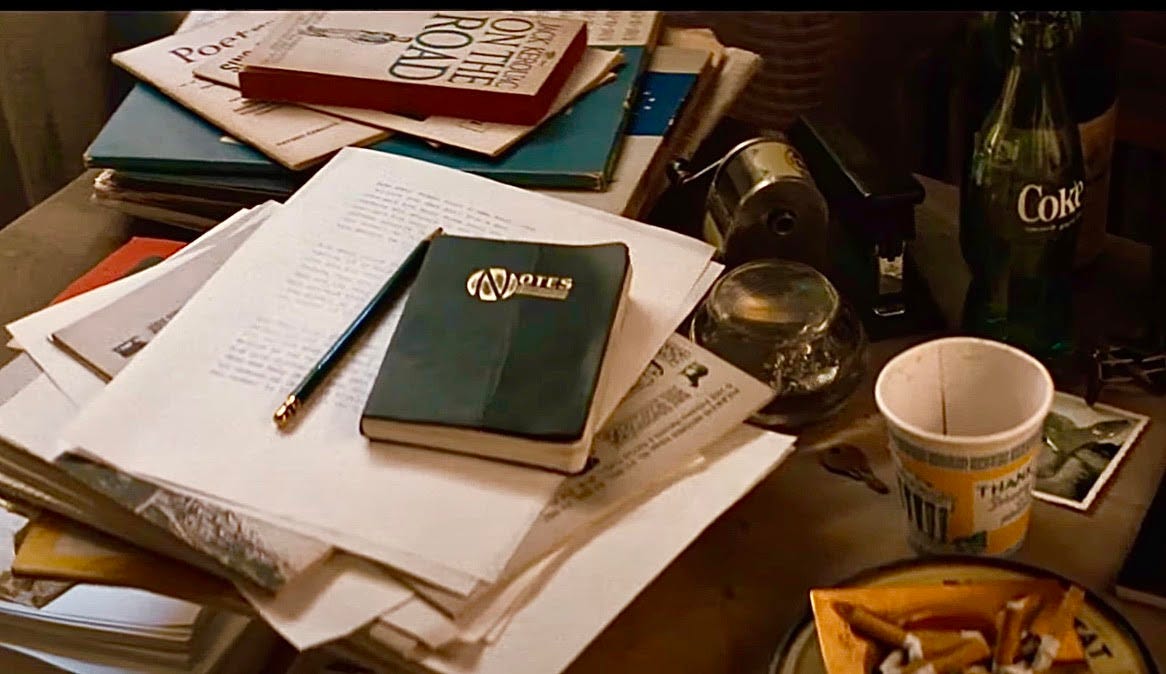

Pictured above: Dylan’s writing desk in the movie A Complete Unknown replete with his copy of On the Road. Hi-res screen grab at 45’25, courtesy of Brian Hassett

The rock carousel chugged on its globe-trotting way – the US and Canada for six months, Australia and Europe for two – well into the following year, replete with the shattering cries of ‘Judas’ at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, a scream of spite that truly embodied the fervour of some of his disillusioned followers, as the huge concert itinerary drew to a close.

If the exuberant journeys described and celebrated by Dylan’s favourite writers seemed to be a positive metaphor for life itself – progress, forward motion, sun up, sun down and anticipation of the next thing – these new trails, these relentless, grinding rock tours, were more grudgingly taken on by a singer increasingly caught up whirl and wail of fame and adulation. Exhaustion and the excesses of the concert circuit were wearing him down.

But Dylan’s motorcycle accident, not long after in July, would necessarily sideline him for an extended period, an enforced moratorium for a young man already disillusioned with the fierce and furious reaction to his acoustic switch and scarred by the testing rigours of gigging. Newly married and retreating to the bucolic pastures of Woodstock in upstate New York, it would be eight years before he returned to the performing stage in a committed manner, finally re-linking with the Band for a world-spanning schedule in 1974.

In the midst of the comeback, he would also produce a string of albums which represented some of the very best of his career output – Blood on the Tracks and Desire among them – and undertake his extraordinary Rolling Thunder Revue expedition from October 1975 and running deep into 1976, a clear indication that Dylan now saw the road once more as a place with escapist appeal, a distraction maybe from the marital woes that had haunted him in the early years of that decade.

One of the earliest dates in the Rolling Thunder schedule, an odyssey that would arguably form a test-run for what would eventually transform, by the later 1980s, into Dylan’s so-called Never Ending Tour which still rolls ever on 25 years into this century, would witness an extraordinary tribute to an artist who continued to sit at the centre of his pantheon of heroes.

Visiting Lowell, Massachusetts, with fellow tour member Allen Ginsberg, the pair paid a most moving testimony to Jack Kerouac, reciting the novelist’s work as Dylan strummed a guitar and the veteran writer sat on the ground and declaimed at the novelist’s hometown grave.

Yet it was not On the Road at the heart of this immensely touching interaction of singer and poet, caught in the angles of the autumn sun at the edge of the author’s eternal resting place, but rather Mexico City Blues, still probably Dylan’s most preferred work from the late writer’s voluminous catalogue.

Here was a tender drama played out in the very city where Kerouac had been born in 1922 then buried there a mere 47 years later, a victim of organ failure resulting from his crippling alcoholism only weeks before the 1960s came to a close.

Dylan’s heartfelt gesture reminded us that, if Kerouac were no longer a reliable model or even a living blueprint, the singer’s commitment to the memory, to the output, of his one-time literary hero had hardly ebbed.

But it was a less likely text, not the most obvious we might claim, that would embroider this poignant encounter. The road continued for sure but On the Road, a novel read by Dylan almost certainly some 15 years before, had been left on the shelf.

See also: ‘Film review #1: A Complete Unknown’, January 8, 2025; 'Book review #36: Dylan Goes Electric!’, December 11th, 2024; ‘Book review #16: Bob Dylan in Minnesota’, July 4th, 2023; ‘The legend of Zimmerman’, September 24th, 2021

When you say that Mexico City Blues was unavailable in the UK, can I assume you were/are based in Britain?

An older cousin gave me a copy of On the Road for Christmas when I was 14 in the early eighties. I put it aside, not knowing anything about it. Then, having read a couple of Dylan biographies plus No-one Here Gets Out Alive, the Jim Morrison bio, and seeing this book being mentioned as influential to them, I picked it up. I then bought everything Kerouac had written and, in 1993, when I visited San Francisco by chance or happen-chance, I discovered as many old haunts as possible, including the house where the Cassady's had lived, and of course City Lights where I exchanged a couple of words with Lawrence Ferlinghetti - thus making my life complete - and, finally, got hold of a copy of Mexico City Blues, apparently unavailable in the UK at that time.