Philip Whalen talks to Steve Silberman

Celebrating the Six Gallery, a poet and a journalist

THERE ARE FEW greater moments in the myth-making of the Beat Generation than the poetry reading which took place at the Six Gallery in San Francisco on October 7th, 1955. The occasion allowed an as-yet-unestablished Allen Ginsberg to read his long poem ‘Howl’, speak his mind and heart without constraint, and attract the attention of key figures in the city’s artistic renaissance, a heady arts revival with poetry at its core.

But the evening was not just about Ginsberg. He was on a bill that included some of the well-known figures on the Bay Area scene – like MC Kenneth Rexroth – and other rising young lions such as Michael McClure and Gary Snyder. Completing the lineup were Philip Lamantia and Philip Whalen.

In July of this year, I received a document of great interest from Steve Silberman, a science journalist of note, a Naropa graduate, a former assistant of Allen Ginsberg, a Grateful Dead follower of huge knowledge and commitment and a long-time friend of David Crosby.

He had been commissioned to write a piece for Rock and the Beat Generation, an idea that had temporarily fallen through, but he remained keen to contribute to our website – our crossover of popular music and Beat literature appealed to his interests – and, out of the blue, he had discovered an old, yet unpublished, interview he had conducted with Philip Whalen himself, with the topic of the Six Gallery reading well to the fore. ‘Would I like to run it?’ he asked. I was delighted to say, ‘Yes.’

On August 29th, 2024, the surprising and sad news filtered through that Steve Silberman had unexpectedly passed on in the city of San Francisco, the place where he had made his home. We would like to see this conversation with Whalen, originally conducted on July 16th, 1993, as an anniversary commemoration of the original unveiling of ‘Howl’ but also a memorial tribute to the late, and much admired, individual who undertook the interview with the poet.

The context of this wonderful exchange – how, why, where? – has now been lost but the value of this tête-à-tête for Beat scholars is immense: a vital moment in the gestation of a literary evolution covered by a player less covered, less heralded, yet a key participant on the night. Questions posed to Whalen, who would die in 2002 aged 78, prompt a series of revealing and fascinating answers…

Steve Silberman: Tell me about what was happening in the Bay Area just before the Six Gallery reading, the cultural landscape that was already in place.

Philip Whalen: There were things like the King Ubu Gallery, which preceded the Six Gallery, for example. I think Robert Duncan was hooked up with the Ubu outfit. At some point, somebody got up a production of Duncan's play called Faust Foutu. Or maybe Faust Foutu was done at Black Mountain College, and then something else was done here, I can't remember.

What I remember about the reading at the Berkeley Little Theater in 1956 was a big banner – a very long, not terribly wide banner, that Bob LaVigne painted, of a naked lady throwing her arms about. There was an enormous audience and a great many poets who read. I can't remember who all was there, besides Allen [Ginsberg] and Gary [Snyder] and Michael McClure and me. I don't know whether Philip [Lamantia] was there or not.

The other thing I remember is Michael reading his one-word poem ‘Light’. And then afterwards meeting various people in the audience who I didn't expect to see. I thought it was quite interesting that they had come – that Alan Watts, for example, and various other people from the city had showed up in Berkeley for this occasion. Rexroth was there.

SS: Was the audience there because they had heard the buzz about the Six Gallery reading?

PW: Of course. Also, there had been readings after the Six Gallery reading, readings that Ruth Witt-Diamant had arranged out of the San Francisco State Poetry Center, which were produced at the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Center on Filbert Street in North Beach.

SS: How long before the Six Gallery reading had you arrived in town?

PW: I'd been here before. I'd come back, I think, in September, because the fire season up in Washington was late that year. I got a room that was being vacated by Will Petersen, who was going to go to Japan, and ended up having this room in this house within about two blocks of Telegraph Avenue. I had been up on the lookout that summer.

Gary had written to me saying that there was going to be this poetry reading, and they wanted me to come and be in it, and that he had met Allen, and that it all looked like it was going to be quite wonderful, so hurry on down. So I came down to Berkeley and stayed with Gary, at his place, temporarily, until Willy cleared out of his place where he was living, and I took it over.

It was '55 that I came down out of the Forest Service. I was living in Berkeley by '56. But, I forget whether Allen had given me that cottage or not. So, where was I living? I don't know. I was in Berkeley some place, I guess, in 1956.

SS: You met Allen through Gary?

PW: Yeah, they had set up a dinner engagement between Allen and me. Jack [Kerouac] was in town, and Jack and Allen were going to meet us at the station at First and Mission Street where the trains would come in from Berkeley. We came in on the train and met them down on the corner at First and Mission. And then we all went off to North Beach and had dinner, as I recall. I forget whether we ate dinner in North Beach or Chinatown. Anyway, it was a very pleasant occasion.

SS: You met Jack and Allen on the same night?

PW: Yeah.

SS: What was your impression of them?

PW: That they were nervous and funny.

SS: Did you consider yourself a poet at that point?

PW: Yeah, I think so. I had started working on a long poem right then that summer, ‘The Sourdough Mountain Lookout’. It was that summer, '55, that I was staying with some friends in Seattle, and they had some friends who had got onto a whole box full of peyote buttons. They were actually fresh peyote plants that you could plant in your garden, that came from El Paso or some such place. They paid a dollar or five dollars or something like that, and it all came by mail or UPS or something.

Pictured above: Philip Whalen, 1923-2002

They had heard that it would make you hallucinate, and they had heard that what you were supposed to do is to pull all the fuzz out of the little pockets of fuzz in them, and slice it up and eat it. Ideally, eating it with soda crackers took away some of the evil taste in it, but it's not really true. It tastes quite unusual. It tastes quite like earth, like eating a mouthful of earth with soap in it, sort of.

Anyway, at some point, either while I was still in Seattle or just after I got up to the Lookout, I wrote some poem that was different from the stuff I had done before. And I started writing pieces I thought were going to be ‘The Sourdough Mountain Lookout’.

SS: Before you came down to the Bay Area, what was your feeling about whether San Francisco was a happening place culturally?

PW: As far as I was concerned, it was absolutely the greatest possible place to be at. I didn't think about it as a cultural phenomenon at all, but as a city with an ocean in it, and a large Chinatown, and various other attractions like that, and museums and the aquarium and everything else. And it had a library. Then, after I lived here for a while, I found out that there was a private library to which you could subscribe if you were properly introduced, called the Mechanics' Institute. It's down in the Financial District.

They've got a marvelous collection of books. Gertrude Stein used to get books from there when she was young. I forgot that it was here until a friend of mine was waving some book at me and I said, ‘Where did you find that?’ And, he said, ‘Oh, the Mechanics' Institute.’ It's sort of like a club or something. You have to have a member of the outfit sign a voucher or something like that, to say that it's okay for you to be a member. And then you give them X amount of dollars a year. It had very pleasant rooms in this office building.

Besides having the library, there was a chess club that belonged to it upstairs, above the library, and that was interesting because there were all these chess tables around, with people wildly concentrating, doing chess. I never tried to do that. It was just interesting that it was there.

SS: Did you have any sense that there was also good music or good painting or that sort of thing going on here?

PW: Yeah, but it all seemed to be very expensive for the most part.

SS: Was there a sense that there were a lot of young people here?

PW: I don't remember identifying with young people or anything else. The first time, I was only here for a short time. It was 1951. I don't seem to remember any particular accent on youth, as they say. So I ran around looking at a lot of things by myself, and sometimes there were young people, and sometimes not. It didn't make any difference to me.

SS: When did you connect with [Kenneth] Rexroth?

PW: Much later. I met him the first time at the Six Gallery reading, I think. Then later on, he would have these Friday evenings at his house where, if you called him up ahead of time and asked him could you come over, he would say yes or not, depending on whether he was having a Friday evening or not. That was always very interesting, because there were young poets there, and older ones, and visiting luminaries from different professions and arts and whatnot. So it was very interesting to be there.

People said it was boring to go, because Kenneth talked all the time. I thought Kenneth was a marvelous talker, and I enjoyed listening to him. So, I didn't mind whether anybody else famous was there or not because he was always entertaining, I thought. Everybody thought he was a big bore except me. I liked his style, his Major Hoople style. It was great.

SS: Do you recall who you might have met there?

PW: There were various European folks, and I remember meeting Lawrence Halprin, the architect and designer. That's about the only one that comes to mind instantly.

SS: Were you familiar with Gary and Allen's poetry before the Six Gallery reading?

PW: Well, I knew Gary's poetry from college, but I didn't know anything of Allen. The only thing of Allen's I knew, but I didn't know what it was, were the letters that appeared in [William Carlos Williams’] Paterson. And I asked Williams, just generally, ‘Did you write all those letters that are in Paterson?’ And he said, ‘Oh, no. Those were real letters.’ Here I was ready to kill myself and become his slave, if, indeed, he had composed all that stuff. So he missed having a slave.

I didn't know who Allen was at that time. I think he was still in the lunatic asylum, and Williams tried to explain that this was so, without naming any names or anything, because he didn't want him to be embarrassed. But Gary and I and Lew Welch and Bill Dickey and Lois Baker and lots of other people contributed to the college magazines. And then, being that Gary and I were living in the same house for some time, I saw a lot of his stuff in manuscript.

Also, Lew [Welch's] material, his early poetry, at that time. I also saw him personally later on. We were living in the same house on Beaver Street, and I saw a lot of his stuff in manuscript, such manuscript as there was. He was very lazy about writing stuff down. He would carry things around in his head for a long time before he wrote them down. And after he wrote it down, he wouldn't like it.

He'd say it was no good. In that respect, about how he worked, and how he put the stuff down and so forth, and later would say it was no good, he was very much like Jack Spicer in that respect. Only Spicer would write revisions or talk about writing revisions. Lewie would actually do a revision or something and fix it and stop.

SS: When you came down here, did you have a sense that Spicer and Duncan had a scene going already?

PW: I didn't know about Duncan. Never heard of him. Didn't have any idea. Some friends of mine who had been living here for some years knew Duncan and told me about him, and that I should meet him some time, but it never came out that way. So I didn't meet him until much later.

SS: I once heard Gary remark that one of the striking things about the Six Gallery reading was that, before that night, he felt that he had friends who were interested in poetry, or friends who were living a certain way, but then he walked into the room, and all of a sudden, he realized there were more than 100 people there who were interested in this stuff. Did you have a similar sense of surprise at the interest?

PW: Well, I was surprised that people would laugh when it was in the funny parts and seemed to be listening and seemed to be having a good time. The audience was extremely receptive and pleasant. So it was a surprise because I didn't expect anybody to pick up much on the kind of stuff I was doing, for sure.

Pictured above: Steve Silberman. He wrote for Wired and published the book Neurotribes in 2015

SS: You read ‘Martyrdom of Two Pagans’ and ‘Plus Ça Change’?

PW: I forget. Probably the ‘Martyrdom’ poem. McClure still likes that, and I don't know where the other part went to. I can't find it. It might be in that Evergreen Review, I don't know.

SS: Did you have a sense that night that it was historical?

PW: No. It was just a lot of fun. It was quite interesting that so many people were there, and everybody was all excited. We all felt happy about it. But, it didn't seem to be special at all. It just happened. There it all was. Something had happened and it was nice. Like your friend said, nice is cheap.

SS: Was that the first time you heard ‘Howl’?

PW: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

SS: What was your first impression of the poem?

PW: That it seesawed back and forth between terrific invention and sentimentality, or what I thought of as sentimentality at that time. That's the word that I wrapped around it somewhere. There was something of the same thing about Jack's work, also, as much of it as I saw in those days. I think it was actually the mutual interest they had in Dostoevsky and in the tender characters like Alyosha or Prince Myshkin, which they dug. And, also, their interest in Melville's Pierre, the great loser.

So, there's a great, great feeling of pity ... Isn't it too bad that these terrible things happened to such nice people, and so forth. To me, Myshkin was just there. He did whatever he did, and so what? I mean ... I didn't think of it as sad or too bad or whatnot. And, the same about Pierre. Pierre was a spoiled brat, for the most part, who had a terrible comeuppance in the end. That was quite an interesting peripeteia, as Aristotle would say.

SS: Allen only read the first part of ‘Howl’ at the Six Gallery, but at the Berkeley reading, he read the rest of it. Do you remember any sense of the poem's energy as an oral performance? Did it seem special?

PW: Oh, yeah.

SS: In what way? Could you talk about that?

PW: No.

SS: No because you don't remember?

PW: No, I don't remember, except that it was very exciting. And Allen getting so excited while doing it. It was, in a way, sort of scary. You wondered, was he wigging out, or what? He was, I guess. But, within certain parameters, like they say.

SS: Did it seem like a personal breakthrough for him?

PW: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. It was a breakthrough for everybody, actually, I think, because nobody had come out and said all the kinds of things that he was saying – a mixture of terrifically inventive and wild language, and what had hitherto been forbidden subject matter, and just general power, was quite impressive. A friend of mine composed a rather savage epigram on the occasion, however: ‘Words of treacle, words of might, fin de siècle joys tonight.’ [‘Siècle’ pronounced like ‘treacle’.]

SS: Who wrote that epigram?

PW: A guy at Reed College named Robert Allen.

SS: And that was on which occasion?

PW: I'm not sure whether it was at the Berkeley reading or a much later reading.

SS: Do you remember going out to dinner after the Six Gallery reading?

PW: We very likely did, but I've blanked it out somehow. I doubt that we had any dinner before the thing happened.

SS: I'm told that you went out to Sam Wo's with Rexroth afterwards, and that Rexroth told Ginsberg that the poem would quote-unquote ‘make his name from bridge to bridge’, or something like that.

PW: I don't remember that, but it's probably true.

SS: Did Kenneth seem very moved by the occasion?

PW: Oh, yes. There was this little wooden fruit crate in the front of the stage, and he came up and said, ‘What is this, a reading stand for a midget?’ or something like that. ‘Somebody's going to come up here and read a haiku version of The Iliad?’ He said he'd been doing so many square jobs recently, it was a pleasure to get away and do something about poetry, and be the master of ceremonies, and introduce everybody. So he did.

SS: Between the Six Gallery reading and the Berkeley reading, was there a sense that word was getting around about you guys?

PW: Not as far as I know, no. I wasn't thinking about it. I did get to watch Allen working on revisions and fixing things because Ferlinghetti wanted to print the thing. So Allen was trying to prepare a clean copy of the whole thing. And he was busy looking at his manuscript notes and previous versions in typescript and so on. And Jack was hovering about, making suggestions I suppose. I don't remember, really. But he was there sort of goofing around.

SS: Where was this?

PW: In Berkeley, in the Milvia Street cottage, which no longer exists.

SS: Did you have any input into Allen's revisions?

PW: Yes, but it reflects great dishonor upon me. I'm sorry to say.

SS: Why?

PW: I asked him what ‘bupkes’ meant and he says ‘garbanzo beans’. Then he said, ‘Oh, I'll change it so that nobody...’ And I said, ‘No, no, don't change it– I like the word “bupke”.’ But he says, ‘No, I don't want to use that. People don't know what it means. I'll change it to “garbanzo”.’ So I feel terrible about that because I liked that word so much.

SS: Is ‘bupke’ Yiddish?

PW: I guess so. Or maybe Russian. The Russian word for beans is something like 'боб’ [pronounced ‘baub’].

SS: So would Allen walk around when he was revising, and would he say the poem aloud to himself to figure out how things were sounding?

PW: Well, he was looking at it and typing, and once in a while he would recite some of it to see what was happening. Then he would change things or not.

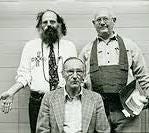

Pictured above: Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Philip Whalen in later years

SS: Would he recite things and then ask you how things sounded, different versions?

PW: Mainly he asked Jack. I just happened to be there sometimes.

SS: So by the time you got to the Berkeley reading, you had seen him working on the manuscript. So you were familiar with the poem already or at least parts of it. Was that the first time he read the entire poem?

PW: You were the one who said so.

SS: Allen told me that.

PW: The thing is, what did he read at the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Center? One of the readings that happened between the Six Gallery reading and the Berkeley reading.

SS: I don't know. That's interesting. How many were there?

PW: Allen did one and McClure did one. Gary did one. I did one.

SS: I see.

PW: Rexroth told Ruth [Witt-Diamant] – she liked Kenneth, and thought we were funny, so she went ahead and did it.

SS: After the Six Gallery reading, did you feel that there were a lot of eyes on you or whatever?

PW: Not really, no.

SS: But all of a sudden there were all these people showing up, including famous people, showing up at the Berkeley reading. So there must've been --

PW: I was quite sure they had come there to see Allen.

SS: So there was some sense that Allen had made a sensation.

PW: Oh yes.

SS: How did that sensation communicate itself? Like were people around the city talking about ‘Howl’?

PW: I don't know, because I wasn't living in the city. I was living in Berkeley. Certainly just going by the audience response at the Six Gallery, and at the Telegraph neighborhood outfit, and at the Berkeley reading, that people were getting turned on, and were very excited about it, and admiring the lot and so on. That's what there was.

SS: Did that change your own work, or give you any kind of encouragement or direction?

PW: Oh absolutely. Because I had started this ‘Sourdough Mountain Lookout’ poem and I could see how it could go on at some length, and that you could spread yourself out over quite a flock of lines, and move around inside of it in various ways, and to make a structure on the outside that came from the inside, just like [Charles] Olson says. And it was very liberating kind of thing to go ahead and 'throw the words around’ as Kerouac used to say. Something like that.

Kerouac was charmingly encouraging. One day he said to me, ‘You know, you ought to write a novel and make some money.’ So I said, ‘Uh huh.’ He says, ‘You could write stories for the Saturday Evening Post.’ I said, ‘That's nice.’ And he says, ‘You can do dialogue real good, so you ought to do that, right?’

And of course, by that time I was old enough, and experienced enough, to know that writing stories for the Saturday Evening Post was a skill that I did not possess and wasn't about to develop. It would take a matter of years, I dare say, to do that. A friend of mine set out to do that on purpose and accomplished his purpose and made a certain amount of money. But it sort of gently faded.

SS: Who do you think were Allen's models for reading aloud?

PW: I don't know. I have no idea. I don't remember him, for example, telling me that he thought Mr. X, the actor, had a really terrific voice or something like that. I don't remember his mentioning hearing different famous ones read.

He and Jack somehow visited the late Mr. Auden, so they must've found out what he sounded like, but I doubt that he sounded like Allen in any case. And they probably heard all the ones that you might hear if you were hanging around the university. You'd probably hear visiting poets like Allen Tate and Randall Jarrell and people of that generation.

SS: Wasn't there also a big Dylan Thomas tour in the early fifties?

PW: Oh yes. And Ruth Witt-Diamant brought him out to SF State College also. So he was here I think– I forget whether he was here once, or whether he was here twice. In any case, she put him up at her place and entertained him, arranged people to meet him and things like that.

SS: Did you ever see him read?

PW: Nope. I've only heard a phonograph record of ‘Under Milk Wood’ and then ‘A Child's Christmas in Wales’. And then, I saw the movie of A Child's Christmas in Wales also, which is quite wonderful. You know, he trained as an actor and toured around with some provincial acting company for a while. So he learned how to do that.

SS: There's a kind of a current stereotype that poetry readings in the Fifties – after the Six Gallery reading – became very swinging events. Did you feel a qualitative change in what poetry readings meant to people, or what they felt like to be at?

PW: I don't know that I thought much about it.

SS: Apparently on the box set that Allen's working on, there's ‘Howl’ and maybe ‘Sunflower Sutra’ from that Berkeley reading. Do you have any other reflections on those poems? On oral performances or cultural events?

PW: I don't think in those terms, I'm sorry. And certainly not at the time that it was happening. It was just stuff that was happening, and it was interesting to be with Jack and Allen in the railroad yard, and Allen discovered this desiccated sunflower, and wanted to know what it was. I thought it was a sunflower.

SS: So you were there too?

PW: Yes. So Allen says, ‘Blake has that wonderful thing about “O sunflower, weary of time, why art thou”,’ et cetera. He was going on about Blake and so forth. I don't remember it being exactly right on the spot that he began writing it down, but he certainly did write it down shortly thereafter. I think he says in a note on the poem in the collected edition that I was there. Or not. It doesn't matter.

SS: I think he wrote it at the cottage. I think Jack wanted to bring him to a party, or something like that, and he was like, ‘Wait a minute, I'm writing a poem’, and he wrote it in 10 minutes or 20 minutes or something.

PW: Yeah, Jack wanted to go to parties a lot.

SS: Do you remember hearing ‘Sunflower Sutra’?

PW: I remember how he read it, but I forget on which occasion he'd read it. I've heard him read it several times, and I know how he sounds when he reads it, but that's all. I can't nail it down to a particular place or time.

SS: I'm going to ask you a question, and please forgive me for the terms in which I'm asking you this, it's probably just the way that I think. To write a poem called a ‘sutra’ is to – especially when it concerns an emotional experience that one has in a railroad yard – is to make a sort of ordinary spiritual experience the subject of poetry, in a way that might not have been very prevalent in the academic verse at the time. It strikes me that one of the most powerful things about the writing that you and your friends were doing at that time was that you made spiritual insights or insights into the nature of reality an acceptable subject for poetry. Yet without exalting them, but expressing them in sort of terms of ordinary experience. Am I making any sense?

PW: What are you driving at exactly?

SS: Did you have a sense that you were making it OK to talk about such experience in poems?

PW: No, because it seemed like that's what poets had done for a great many centuries. If you read the early Greek lyric poets, or very old Chinese poetry, or almost anything, the poets usually do that. Some of them go overboard and ecclesiastical, like Wordsworth did, and write the 500 ecclesiastical sonnets or whatever, however many there are. Various other sort of Orthodox religious routines go on to some length. But certainly the vibe that Blake puts out is somewhere in there quite heavily, I think in all of us.

I remember in college that Lloyd Reynolds was very, very solid, and very specific, and very strong on Blake as a poet and artist and so on. And certainly there are moments in Whitman, like in ‘Song Of Myself’ and even more certainly in Emily Dickinson, there are trips that are just absolutely terrific, done in four lines and in ordinary language. And you know, without saying ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ and ‘whither’ and ‘thither' and ‘thou art’, et cetera; what people, when I was young, took to be the language of poetry – sort of King James English, or something.

But Chaucer is certainly very straightforward and very beautiful. For example, ‘Youre two eyn will sle me sodenly’ – to get ‘slain suddenly’ is pretty tough stuff. ‘I may the beauté of them not sustene’. Certainly Coleridge could do it from time to time – looking into all these weird sea creatures skipping and bouncing in their phosphorescent light, with the ancient mariner looking over the side of the ship, gets totally turned on by that vision, and felt that he could bless them and be blessed, or something like that.

SS: Now all that group of you and your friends can be gathered together in a single book like Ann Charters’ Beat Reader.

PW: Oh, that makes me very nervous. I have always resisted the idea of being a group, for some reason or other. That wasn't the point of... I don't think poetry was the point of our being together. We just liked each other, and liked what we were doing, and we were all trying to do the same thing, and trying to do something that wasn't going to come out like Archibald MacLeish or something [laughing]. Something that wasn't going to be – oh, what is that boy's name?

He was the white hope in the Thirties. The one who wrote ‘on a naked bed in Plato's cave, the headlights sliding down the walls’, et cetera, et cetera. What's his name? He's still got a heavy following among serious academics. I can't think of his name. It's too bad. [Delmore Schwarz – SS] This seems exquisitely boring to me, because as I say, I don't remember anything.

And at the time, all this excitement was being exciting, it was just what was happening, and I didn't pay much attention to it as excitement or something – unless I was, with the exception of watching Allen revise his things, and watching Jack type right out of his notebook, and laugh, and add stuff, and make mistakes, and add other things, and cut some things, and not copy some pages, and things like that. There was this very strong drive to make something.

One day, we were all sitting around that cottage, yakking about something or other. Gregory [Corso] was there, and finally Gregory says, ‘Why don't you people do something beautiful like Shelley? Why don't you write poems or something, instead of just sitting here yakking away? What's the matter with you?’

SS: So I've been reading Allen's work and yours since I was in high school.

PW: I can't imagine such a thing, I'm sorry.

SS: Yet it's true.

PW: The thing that's wonderful is that Allen would always tell all these magazine editors who asked him for poems, ‘I will give you some poems, but I'd like you to print some poems by Gary Snyder and Phillip Whalen, if you please.’ And they would say, ‘Oh, all right.’ So we got printed, which was a great break, and I'm sure that probably Allen turned Donald Allen onto the idea of including us in his anthology [The New American Poetry].

Allen has always been extremely generous, and has seen to it that the Committee on Poetry has given me money from time to time when I needed it. And arranged grants from the Academy of Arts and Sciences or whatever. And he entertains me at his house in New York when I go there. And had me come and read to his classes in Brooklyn College. And he has been a tremendous friend all this time. Which is considerably more important to me than whatever stuff we manufacture. I just feel very grateful to him and for having known him. He's a terrific person.

Editor’s note: This article is dedicated to the memory of Steve Silberman, 1957-2024, who wrote to R&BG on August 7th, 2024, but never completed the mission he described:

‘Simon:

I edited the interview and it's mind-blowing, to me anyway. A nearly lost gem.

I will write a short intro in the next week or so. Enjoy.

Steve’

Steve left us too soon. Rexroth was always very charming altho I was a decade after Six Gallery down on the scene - I met Robert Duncan who was quite a character and I dig the Delmore Schwartz reference who many consider to be an influencer of first person confessional poetry - the Reed Collegepoets always fascinated me cos they were in many ways so North by Northwest a cosy coven all their own

This was wonderful. A really valuable interview. Thanks for sharing it.