Ted talk: Keeping up with Joans

African-American Beats are a rare and precious commodity. In a guest blog, our reporter CJ Thorpe-Tracey catches a key and expansive work by one such individual at London’s leading art gallery

Writer, broadcaster and composer CJ Thorpe-Tracey has written for the Quietus, Dark Mountain, the Morning Star, New Public Thinkers and others. He runs The Border Crossing newsletter and presents weekly music radio show Sunday HONK!

He recently caught Tate Modern’s Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition and was intrigued to find poet, artist, jazz obsessive and Beat legend Ted Joans among those on show. Thorpe-Tracey shares his wide-ranging thoughts with Rock and the Beat Generation…

I wasn’t expecting to encounter the Beat Generation at Tate Modern’s Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition but really, I shouldn’t be surprised they showed up.

It’s a large-scale retrospective show (in its final weeks as I write – open through August 2022) that focuses on notable enclaves of Surrealism away from its birthplace in 1920s Paris. Several rooms showcase these convergence points – Haiti, Cairo, Mexico City – but the curation isn’t solely geographical; it’s themed as well, so it can get a bit hotchpotch.

Overall, this is a decent, chewy retrospective. However I’m not sure it lives up to the grandiose (typically Tate-ish) claim of ‘rewriting the history’ of the revolutionary art movement.

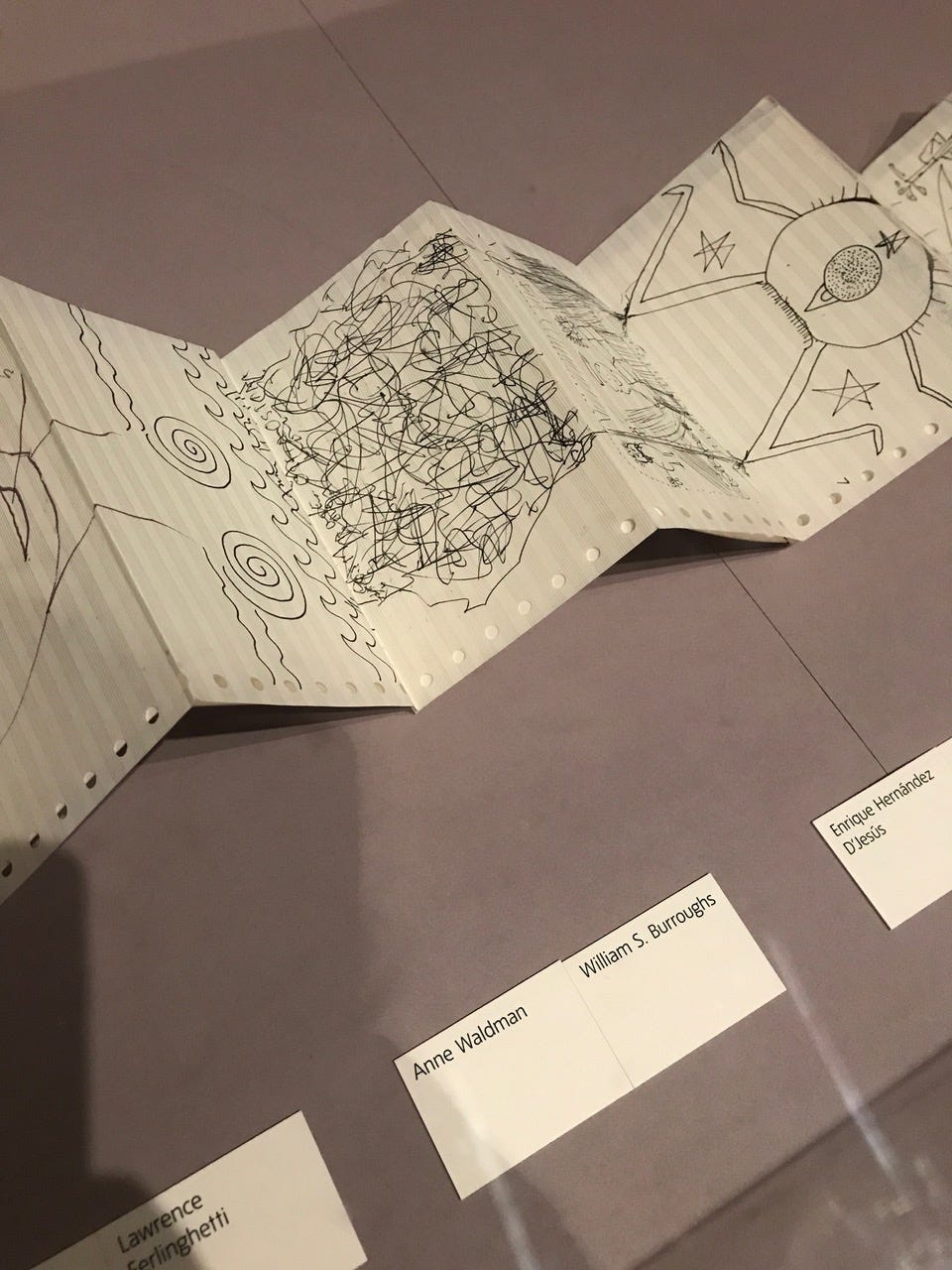

Where Surrealism Beyond Borders brings unexpected Beat joy is in the small section dedicated to the Beat-adjacent African-American poet, musician, artist and traveller, Ted Joans. Along the length of a narrow, dimly-lit corridor, they’ve put on display Joans’ extraordinary Cadavre Exquis (Exquisite Corpse) collaborative paper drawing Long Distance.

And therein lie several great Beat icons, at their most relaxed, drawing casual black-and-white sketches to contribute to the piece. More than any Beat-connected artefact I’ve experienced in a while, Long Distance conveys that essence of actually being there.

If you’re not familiar with Exquisite Corpse, it’s the Surrealist sketching and writing game, played on a long strip of paper. The first player draws a section of a body (or anything), then folds over the paper, leaving visible just the edges of their drawing. Using those edges as a guide, the next player draws the next section of the body (or anything) onto the next section of paper, and folds again. So the game continues.

At the end, you open up the paper to reveal the finished image. It’s an informal, convivial structure for co-creation, presumably best done when shit-faced! Originally it was a word game, with players using the same folding technique to create unexpected sentences.

André Breton named the game after it produced the pleasing sentence: ‘The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine’. Perhaps it can be viewed as a playful sibling art-form to the Dadaist cut-ups discussed by Simon Warner in a recent Rock and the Beat Generation post.

So to Ted Joans, who deserves to be more widely-known. He was born in 1928 in Illinois, to restlessly mobile parents who worked on riverboats. He inherited their itinerant gene. After studying at Indiana University and finding his first artistic love in jazz trumpet, as a young man Joans painted, performed music and wrote poetry. Inevitably, before long he landed in Greenwich Village.

In 1955, reacting to the death of Charlie Parker, he scrawled ‘Bird Lives’ on walls around New York, which had a meme-like impact, pre-empting Basquiat’s phrase-based graffiti on the same streets. Joans’ visual art, though initially rooted in paint, would later expand to include cut-and-paste, found objects and film. He liked rhinoceroses.

Even after giving up trumpet, jazz remained at the heart of his art and verse. I wonder if he is best remembered for one phrase: ‘Jazz is my religion, and Surrealism is my point of view.’

Ted Joans spent most of his adult life travelling in Europe, North and West Africa and across the Americas. By his early 30s he had a house in Tangier. He’d initially left the USA at least partly because of the prevalent racist violence, yet what emerges from his travelling life is a vast and active network of artistic friends, across the period’s most important scenes, for whom Ted Joans became a social touchstone.

Leaders of both the Beats and the Surrealists embraced him and brought him into their inner circles – Joans became close to Dali and later Breton in Paris, as well as Kerouac, Corso, Ginsberg and Amiri Baraka in New York and on the West Coast. Breton called him ‘the only Afro-American beat’.

Joans loved to travel on foot and seems to have walked great distances. Reading up on him reminds me slightly of Bruce Chatwin’s nomadism, though they couldn’t be more different in character. I briefly wonder if they could’ve met, though at least according to Google, they’ve never even been mentioned together before now.

Joans was very adept at sliding comfortably into the social mores of whichever group was hosting him. He thrived beyond the West, spending winters in Timbuktu in Mali, and was in Berlin during the turbulent 1980s, mostly writing jazz reviews.

I think one root of Ted Joans’ power of connection is in his balance of itinerancy and being present, along with his gift for correspondence. Ted Joans was very there, or he was away. And when he wasn’t around, he’d be writing to you. He wrote piles of letters on his travels, corresponding with Charles Henri Ford, Langston Hughes, Stokely Carmichael, Chicago Surrealist Group and many others.

Anyway, one of the great works (and ice-breakers) of Ted Joans’ artistic and social life was Long Distance, this enormous, sprawling Exquisite Corpse that he worked on (well, persuaded friends to work on) for almost 30 years, beginning in 1976. It actually outlived him, Gaudi-like. It was completed two years after he died.

Over nine metres in length, Long Distance was drawn onto thin, blank musical stave paper, like some unfettered composition score. There are 132 different players from around the world, some obscure, some infamous, each contributing a section of illustration. Joans literally carried the remarkable piece with him around the world. And since Joans hung out with the Beats, so the Beats are on there, captured at their most spontaneous…

Lawrence Ferlinghetti uses few lines to draw a simple, yet compelling face, smoking a joint with closed eyes and a lovely, knowing half-smile.

Two folds later, separated only by Anne Waldman’s spiralling boobs, William Burroughs goes full Jackson Pollock with his ballpoint, building frantic layers of scribbled lines to fill the available rectangle.

Perhaps Allen Ginsberg most embraces the surrealism of the moment, while also apparently misjudging where the guide marks are meant to be. He transforms a thick pair of legs into two buildings with large windows, through which people and skylines can be seen. He draws musical notes onto the stave. Someone is saying something. Perhaps the buildings form the letters A and H, though it’s difficult to be sure.

Gregory Corso…actually I can’t tell you what Corso drew, because when I filmed right down the full body of Long Distance with my phone camera, I slid slightly too fast past his section and missed the details. Other contributors include (and this is just a taste): Paul Bowles, Jean Benoít, Brion Gysin, Octavio Paz, Malangatana, Dorothea Tanning, Adrian Henri, Abdul Kader El Janabi, Jim Burns, Michael Horovitz and many more.

Ted Joans died in Vancouver in 2003, taken by complications of diabetes. Long Distance was completed in 2005. I wonder where it usually lives, when it’s not in the Tate.

For me, this is one of those powerfully evocative ‘fly on the wall’ works of art. It can transport you to wherever and whoever. Informal and effortless and silly, yet filled with casual genius, it has the sense of being an artefact: maybe as precious for being an object with a multitude of contexts and its own physical journey – the dust of all those cities – as for what its contributors actually drew. I’ve not felt such FOMO before, looking at a load of pen and ink sketches. Long Distance really does succeed as a kind of musical score for grand social imagination.

I can’t find a proper biography of Ted Joans, nor a memoir. He’s here in Tate Modern, yet there are no recent collected editions or reprints of his poetry, just old editions of his 1973 book Black Pow-Wow. The most recent significant essay I found about him is over 10 years old. Someone should tell his life story properly.

He’s perhaps best found on YouTube, where he pops up in clips about the Beat scene, or reading at a coffee-house gig in Amsterdam in the 1970s. Yet, like a living, human Exquisite Corpse, Ted Joans is the guide marks you see over the fold. He exists as an intersection point, to link these avant-garde disciplines and locations beyond our usual perception of twentieth century art in silos.

Never mind his big adventure of a life, you could write a good book, or make a film, solely about the creation of Long Distance and the unique, co-operative game that Ted Joans instigated at parties, across continents, for more than a quarter of a century.

CJT-T

Note: Simon Warner’s piece on the cut-up, ‘Rip it up and start again’, was published in Rock and the Generation on July 28th, 2022

Heard Ted Joans read at the ICA, London, in October 1970. Three days earlier I'd seen Robert Graves at the Festival Hall.