FOR FOLLOWERS of the Beat Generation, Ann Charters requires little introduction; for followers of jazz and blues history her late husband Samuel holds similar status. Ten years ago this week, on March 18th, 2015, Samuel Charters died aged 85.

To commemorate that notable anniversary, his wife, author of the earliest full-length biography of Jack Kerouac and the woman behind multiple books in the Beat Studies canon, responds to questions from Simon Warner, Editor of Rock and the Beat Generation, about her husband’s professional pursuits, his achievements as a musicologist and historian and the productive relationship they shared as partners over many decades.

Through his long engagement with blues and jazz, Samuel Charters, born in Pittsburgh in 1929, became an important figure in the establishment of Popular Music Studies as a new transatlantic discipline and eventually as a global intellectual force.

A prolific writer, his books such as The Country Blues (1959) and The Roots of the Blues (1981) were highly influential, helping to salvage traditional US and ethnic styles for consideration in the academy and beyond.

Simon Warner: Tell us something, Ann, about your husband’s early engagement with these branches of musical history.

Ann Charters: In 2000, Sam compiled A Checklist of Productions, Recordings, Compilations And Writings For Album Release 1951-2000 for his Gazell Productions in Storrs, Connecticut. In his introduction to the 137-page volume, he wrote:

‘I hadn’t realized, when I began this check-list, that over the last fifty years I had spent so much time in recording studios. I should have kept better notes, but I never thought this is what I would do with my life. I was going to be many things, but record producer was never one of them…. I grew up with music, but it was as a musician, and not a very good one, that I first traveled to New Orleans in December, 1950. I was only thinking of finding the clarinet player George Lewis, and taking some lessons from him so that my own clarinet playing might improve a little.’

Sam remembered that it was during that bus trip from Sacramento as a twenty-one year old that he had an idea for the first of four record albums, starting with ‘all the ragtime compositions of Scott Joplin that had flowers or leaves for titles’ that he’d call A Joplin Bouquet.

In New Orleans ‘I had also heard, for the first time, the great Eureka Brass Band, and I had heard a 78rpm release on a local label of a jazz string band that had been together since 1913 called the Six and Seven-Eighths. I was so excited by the music of both bands that I decided there also had to be records of them. I had already heard the guitar gospel records of Blind Willie Johnson when I was playing in a band in Berkeley in 1948, and his music had to have an album. Four albums: A Joplin Bouquet, the Eureka Brass Band, the Six and Seven Eighths, and Blind Willie Johnson.’

He continued: 'Then I would go on and write novels, find a job somewhere as a labor economist, and finally work for the United Nations. The only things that worked out the way I dreamed of them were the four albums.’

Pictured above: Samuel Charters. Photograph by Ann Charters

SW: His 1959 marriage to you represents, in a way, the perfect example of a coming together of the worlds of jazz and blues and Beat literature. Do you recognize an affinity?

AC: In the autumn of 1954, I first noticed Sam in my music class in ‘Counterpoint’ at the University of California in Berkeley, but we didn’t begin to talk until the spring of 1955, when we both signed into the same section of a class in ‘Harmony’, the second half of the course. I was 18, he was 25, a Korean War veteran married to his first wife Mary Lange.

There was no idea of ‘Beat literature’ in 1954, but Sam drove me over to San Francisco to browse in the City Lights Bookstore. The previous year, after his honorary discharge from the US Army where he’d served as a cross-country ski patroller in Alaska, he had worked for Dun and Bradstreet as a credit investigator. Sam had written the positive report that helped Lawrence Ferlinghetti and his partner get the funding for the stock of paperbacks they needed to open their store.

SW: Did Sam Charters take an interest in the Beat Generation as a literary community and as a radical social force? Did you yourself have connection with the musical forms which interested him? Or did your intellectual pursuits happen independently?

AC: Sam introduced me to the so-called ‘protest literature’ of Beat poets, such as Allen Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti, and to the little magazines of the 1950s that published Black Mountain poets such as Charles Olson and Robert Creeley. I was immediately attracted to their writing.

As an undergraduate English major at UC Berkeley, I wanted to read everything. Also I had studied the piano for years and loved ragtime, though I’d found the sheet music only for Scott Joplin’s ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ in Rudi Blesch and Harriet Janis’s book They All Played Ragtime in my high school library.

Pictured above: Ann Charters, a key Beat historian

For years Sam had been ‘junking’ old jazz and blues 78 records in Salvation Army and second-hand stores, and he had a collection of the original sheet music by Joplin and other classic ragtime composers, so he put me to work playing Joplin ragtime for his first album, A Joplin Bouquet.

I recorded A Joplin Bouquet in December 1958, when I was living in New York City at International House as an MA student of English at Columbia University on a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. It became the first record for Portents, our own small label.

SW: Did your husband ever meet Kerouac, Ginsberg or Ferlinghetti, Rexroth, David Meltzer, maybe ruth weiss or perhaps David Amram, those individuals who identified a synergy between the new writing and music? Did he discuss music with any of those novelists and poets? Particularly, did his paths cross with LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka and did they every converse regarding his own 1963 history Blues People?

AC: Sam recorded two LPs of David and Tina Meltzer’s music in 1967 and 1969, when he was working for Vanguard Records. They became our good friends. In July 1966 I spent two days with Kerouac at his home in Hyannis on Cape Cod, when he helped me to compile his bibliography.

Some time in 1985 LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka agreed to meet me on Eighth Street in Manhattan so I could photograph him for my book Beats & Company, but he stood me up. He never tried to contact Sam to talk about the history of the blues for Blues People, but he used Sam’s pioneering book The Country Blues without crediting it.

Pictured above: Samuel Charters (right) with umbrella during a rainy parade, protecting the bass drum from the downpour, in Algiers, Louisiana, 1957. Photograph by Lee Friedlander

SW: Sam Charters lived his later life – and died – in Sweden. Did you reside there as a couple ever?

AC: At the end of 1970, Sam and I and our three year old daughter Mallay moved from our home in Brooklyn Heights to Stockholm, where Sam had taken a job as a producer with Sonet Records, a Swedish company. He was 41 years old. This was after he had produced Country Joe and the Fish’s ‘Fixin’ to Die’ anti-Vietnam song for Vanguard Records, and we had considerable royalties.

To protest the war in Vietnam, we decided to move to Sweden, where he accepted his part-time job with Sonet at a 90% pay cut of his salary at Vanguard Records. I had tenure as an English professor at New York City Community College and took a long leave-of-absence. Sam and I made a home in Stockholm.

We wrote the first biography of Kerouac together during our first year and a half there. It was published by Straight Arrow/Rolling Stone in January 1973, after the birth of our second daughter Nora Lili.

When I couldn’t find a job as a college professor in Sweden, I left Stockholm to begin teaching at the University of Connecticut in Storrs in 1974. I was 38 years old. From that time until 2016, I lived in both the US and Sweden. After years of working for Sonet, Sam became a Swedish citizen in 2009.

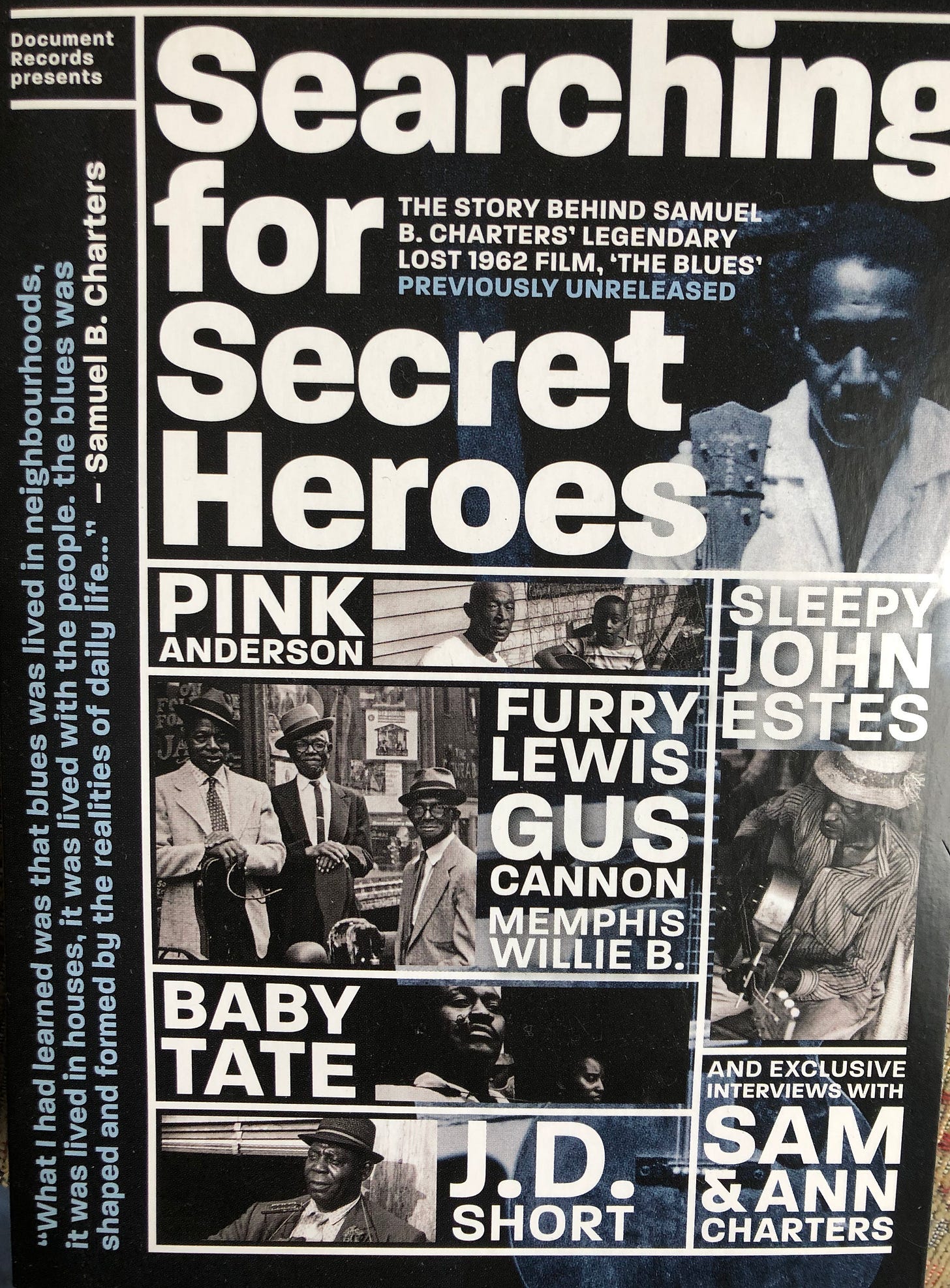

Pictured above: The DVD relating the story of Sam and Ann Charters’ early 1960s search for lost blues musicians

SW: Your husband had fallen foul of HUAC investigations in the early 1950s and decided to pursue his political inclinations through his focus on African-American musical styles which became closely associated with the Civil Rights push. Would you agree that his anti-racism principles were pursued largely through the promotion of and research into jazz, blues and so on?

AC: Yes, definitely.

SW: What was your attitude to Sam’s commitment to popular music research? Were there elements of the Lomaxes’ example in his pursuits? Was he, in some ways, an heir to their earlier fieldwork?

AC: I shared Sam’s commitment to popular music research. Early in 1957, living in a cottage near campus in my senior year at UC Berkeley I decided to marry Sam after he sent me his Folkways Record of Blind Willie Johnson. On the first side he re-released several of Blind Willie’s early gospel recordings, and on the second side he narrated the story of his search for Johnson in Texas.

Sam was too late to find him, but he located Johnson’s widow and recorded her story of her years living with this remarkable singer. After I listened to this heart-rending record, I decided that I wanted to live the rest of my life with Sam. I totally shared his commitment to black music.

John and Alan Lomax were early models for Sam. After listening in the Music Library at UC Berkeley to Alan Lomax’s field recording of music in the Bahamas, Sam took me with him to Andros Island during the summer of 1958, before our marriage on March 14th, 1959.

There he recorded three LPs of music for Folkways, and I took my first photographs of the Bahamian landscape and the musicians on Andros for Sam that he used on the album covers and in the booklets. Sam wrote a wonderful book describing our idyllic summer together searching for music, The Day is So Long and the Wages So Small: Music on a Summer Island (1999).

I don’t think that Sam ever felt he was ‘an heir’ to the Lomaxes’ earlier work. In the 1950s, Sam’s mentor in jazz and the blues was Frederick Ramsey, who lived close by with his family in New Jersey. Ramsey recorded in New Orleans and in the South, and he introduced Sam to Moses Asch at Folkways and became a close friend. Sam and he shared a deep interest in the legendary New Orleans musician Buddy Bolden, for example.

When Sam was beginning his career, Alan Lomax wasn’t publishing books on music, so we didn’t really think much about his work. Our impression was that he was mostly involved as an academic in his projects at Columbia University, unlike his portrayal as a heavy hitter at the center of the folk music scene in the 2024 Dylan film A Complete Unknown.

SW: Would you like to say a little bit about Sam’s own poetry and fiction? Were similar inspirations shaping his work and that of the Beats?

AC: Sam published several books of poetry and fiction, which I encouraged along with his publisher Marion Boyars in England. His biggest success was with his novel Louisiana Black (1986), made into a popular film starring Gregory Hines.

He went his own way all his life. He loved Kerouac’s writing as much as I did. He completely supported my work on the Beats, though he didn’t write like them. On September 30th, 1969, he wrote to Jack, saying that ‘from the very beginning your books were completely it for me. Whatever happened to all of us in America then – all of it’s in your books – and all the dreams we had and all the good times and the lean times and the sad times. Those books – every one of them – are going to be around for a long, long time. Thank you for writing them.’

However, Sam shared neither Kerouac’s disdain for ‘the craft of carefully arranged thoughts’ nor his obsession with ‘the uncontrollable involuntary thoughts themselves’ (Desolation Angels).

Living in Sweden in 1973, Sam and I became friends with the Swedish poet Tomas Transtromer, who won the Nobel Prize in 2011. He was a wonderful poet, and we often visited him and his wife. Sam was one of his several English language translators.

Tomas even described playing four-hand piano at our home with Sam, which they did frequently while I turned pages, and quotes me in his extraordinary poem ‘Schubertiana’. I’m one of the few people Tomas quotes in his poetry. Look up ‘Schubertiana’. It’s worth reading.

SW: I was intrigued to encounter online reference to a book called Some Poems/Poets: Studies in American Underground Poetry Since 1945, a collaboration with you in 1971. That’s a title I would love to see! How did that come about? Would you like to say something about how you worked together as husband and wife?

AC: Sam wrote Some Poems/Poets for Robert Hawley, who published it in Berkeley with his small press Oyez. That book was written before we moved to Sweden in 1970. As Sam said in the ‘Introduction’, he wasn’t trying to explain the poetry of Ginsberg, Olson, Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder, Robert Creeley or others.

He commented: ‘What I’ve tried to do in these studies is to get down some of my own responses to writing . . . with the intention that this kind of opening to an experience of the poem might lead someone to the poem itself.’

Sam included several of my photographs of the poets in this book. At the time I was compiling Scenes Along the Road, the first informal history of the Beats, from Allen Ginsberg’s photographs. Sam designed this book for Portents and saw it through publication before it became a City Lights book.

After Sam collaborated with me in completing the first biography of Kerouac in 1972, he co-authored another biography with me titled I Love about the great Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and his lover Lili Brik, whom I interviewed during four trips to Moscow. It took us six years to write this book, published in 1979 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

We also wrote a book about Kerouac and his friend John Clellon Holmes titled Brother Souls, published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2010. A couple of years later, near the end of his life, I helped Sam do the research in the Garrison archives at Smith College for his last book Songs of Sorrow: Lucy McKim Garrison and Slave Songs of the United States, published in 2015. He never got to see the published book, but I think it’s one of his best.

It was a pleasure helping him with the preliminary research, reading through Lucy McKim’s letters in the Smith College archive together. Throughout our marriage, we did whatever we could to help each other, and he supported my work as much as I supported his. Sam was an exceptional husband. Without his encouragement, there would be no Ann Charters.

Editor’s note: Ann Charters is Professor Emerita of American Literature at the University of Connecticut at Storrs. She has two current titles to her name – Young Tom and Charlie: Two American Poets at Home in Gloucester (2024), concerning T.S. Eliot and Charles Olson, and Jack Kerouac’s Legendary World of Duluoz (2025), a new Beat Scene chapbook

A great interview with Ann. We met them in Oneonta at a student's apartment after a lecture they gave. A had a long conversation about why she didn't include Charley and Janine Pommy Vega in a Gale Research book on the Beats.

Ann Charters biography of Kerouac was my first read on Jack. The accomplishments of Sam & Ann are intertwined with the ecstatic Beat movement that had its antecedents in the San Francisco Renaissance- it’s an inspiration to have their story revealed and the influence of the University of California Berkeley on the dreamscape of Beat San Francisco