A significant figure in the Greenwich Village scene of the 1960s, TERRI THAL was Bob Dylan’s first manager, the wife and manager of legendary singer Dave Van Ronk, a tireless musical promoter, ardent socialist and political activist.

Her first-hand experiences of these times are delightfully conveyed in her autobiography My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me, published by McNidder and Grace in 2023. She remains an avid campaigner for social justice and environmental reform.

Now, Thal has written three related essays on that remarkable Village world for Rock and the Beat Generation, including reflections on the very recent Dylan movie A Complete Unknown and the place of the Beatles in the folk story.

Firstly though, she remembers the Beat poets…and the role of the beatniks.

____________________________________________________________________________

‘The Beats and me’

By Terri Thal

WHEN I FIRST went to the Village with a high school friend in 1954 or 1955, I was 15 and a high school senior. Later, I realized that I had expected to see an Eastern European shtetl – crooked, cobble-stone-paved streets, bright-colored crooked houses with deeply slanted roofs, people who wore long-skirted peasant clothing. But Stu took me to West 8th and West 4th Streets, the former even then a fairly commercial strip; and to a Ted Joans party in a loft on the Bowery – or perhaps on Astor Place.

Even then, I realized that the Ted Joans party was a commercial attraction (it was a rent party). Attendees paid to get in. The guests clearly were tourists, like us. Were the few bearded men and the women wearing slightly Indian-looking outfits or black, wrinkled tops and pants truly Greenwich Villagers, I wondered. Were they the writers and poets and musicians I’d hoped to meet, or were they making believe? Was the poetry Joans read to us to be taken seriously, or was it gobble-de-gook, put together as part of a show? And bongo-drums. Why?

Fast forward to 1960 and the Gaslight Café on MacDougal Street. I again heard Ted Joans reading poetry, and again people paid to hear him…this time in a coffee house. But I no longer was a high school kid looking for a world where I’d have more freedom than in my parents’ home in Brooklyn; I was 20, had graduated from college, and was living with a folk singer who himself was trying to get paid to perform in coffee houses.

I’ve written elsewhere about the Gaslight in its early days. Owner John Mitchell, who had been part owner of the Café Figaro, where everyone I knew hung out, had sold his share in it and had opened the Gaslight against the advice of almost everyone he knew. He hired poets to read publicly in it, and asked the audience to put money in a basket to pay the poets.

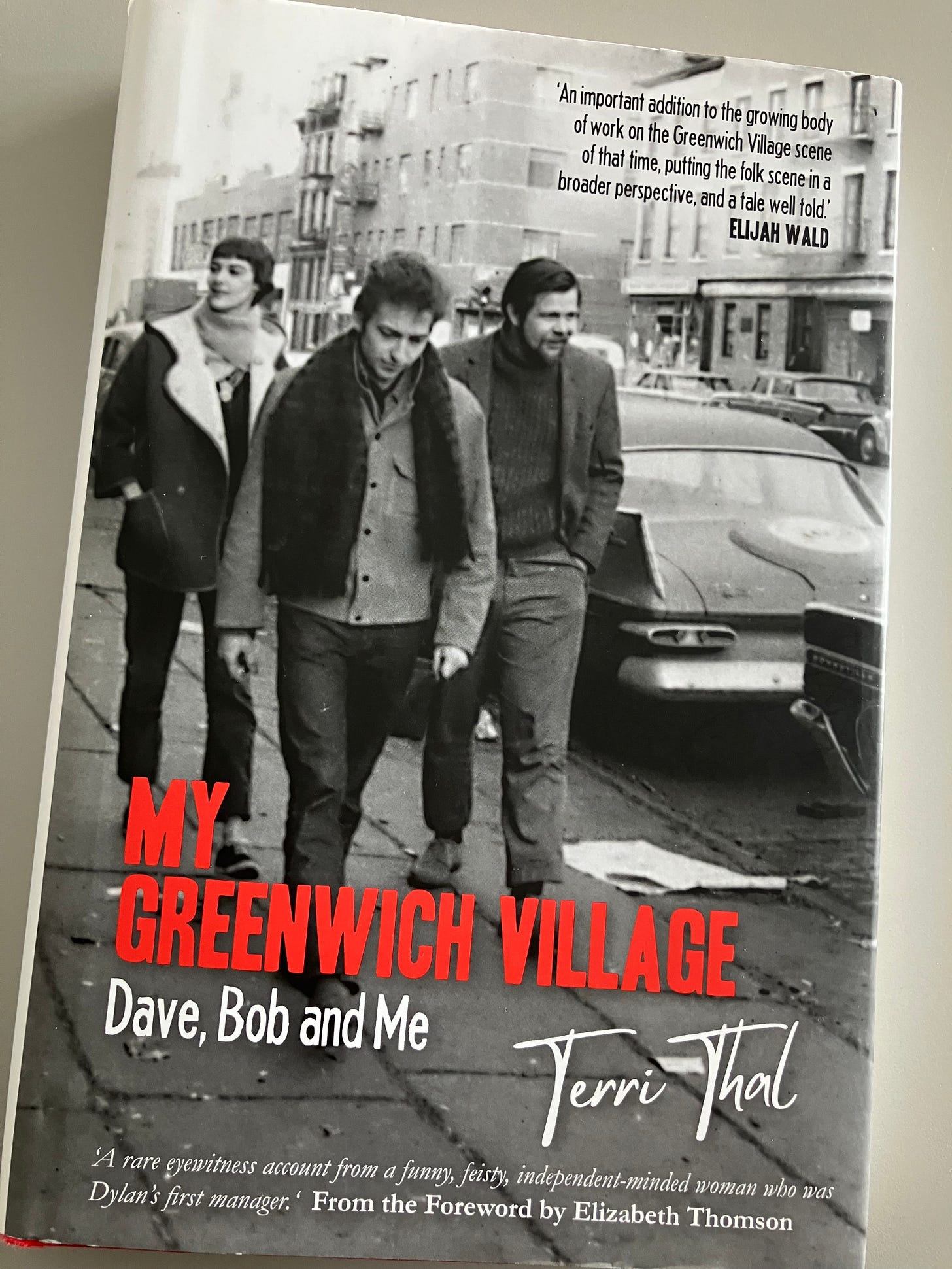

Pictured above: Terri Thal’s 2023 autobiography

In its earliest days, I heard Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso there, although they only worked there for a short time. Then, John brought in folk singers as well as poets; they were intended to drive the audience out between sets so a new group of people would come in eager to shell out money to pay the poets, who by then included Ted Joans, LeRoi Jones– later known as Amiri Baraka – Bob Kaufman, John Brent, Hugh Romney, who later changed his name to Wavy Gravy, and more. Within six months, of course, the folk singers had replaced most of the poets and, after a while, John started to pay them salaries.

When the Beat poets read at the Gaslight I often heard them. Yet I found it difficult to listen to most poetry. I’m primarily visual rather than auditory and, while I could listen to music, if I tried to listen to spoken words, my mind tended to wander away. One of the things that attracted me to folk music was that so much of it told stories. I loved – and still love – narrative ballads and informative songs that speak of work conditions, wars, murders (so many murdered-girl songs!). But, if I tried to listen to someone speak the same ballads, I didn’t hear them.

As I wrote in my book My Greenwich Village: Dave, Bob and Me, once, LeRoi Jones challenged me to listen to poetry readings every night for a week. I didn’t have a week of free evenings, but I listened one Friday through Sunday. It still was difficult for me to absorb what was read. I tried reading it and found the writing challenging, but I felt that I was connecting with it.

I was impressed with John Brent’s rousing rendition of 'Bible Land’ written in 1961 in reaction to news of a plan to build a theme park called Bible Storyland. It was far from the best poem heard then…but it was explicit and sarcastic and I liked it. Somewhere, I may still have a copy. I didn’t realize then that all of those poets were Beats. I did note that none of them were women.

Interestingly, Dave Van Ronk, who I lived with then (and subsequently married and divorced, but remained good friends with), had written a negative review of ‘Howl’, a few years earlier, before we started to see one another in fall 1959, or sometime around then. Dave was only 20 or 21 when he wrote it, but his review reflected his dislike for personal, emotional writing, which remained his perspective for as long as I knew him.

On the Road was about a male escape journey that didn’t appeal to me, but although I had no urge to take that kind of trip and I preferred writing that had structure and generally adhered to grammatical convention that Kerouac’s book circumvented, it was excited writing that spoke of the humanity of the writer. I felt that if I were a man, perhaps I’d want to be on that kind of trip...that it would become mine. Later, reading Visions of Cody, helped me overcome my difficulty with expressionistic writing.

Some of the other people I knew during the late 50s-to-mid-sixties were considered Beats. I had a limited relationship with Moondog, the composer and poet who was known by many as the man who stood on a corner of Sixth Avenue either uptown in the 50s or in the Village dressed in Viking-style clothing. I saw him on the street so often that I took to stopping to say ‘Hello’ to him, got into conversations with him, and heard snippets of his music on records people played for me.

Ann and Sam Charters became good friends. Ann was a very good photographer, pianist and researcher and wrote about the Beats, but I didn’t think of her as one herself. Ann took one of my favorite personal photographs; it’s of Dave and me on the roof of the building we lived in on Waverly Place, and I’ve featured it in my book.

And, she’s the pianist on a wonderful record she made in 1958, titled A Joplin Bouquet, featuring rags written by Scott Joplin, which I still have and play. I didn’t think of Sam as a Beat, either; did he? I knew him as a blues collector, a writer, a record producer, and a great raconteur. He also sang, arranged, and played washtub bass, washboard, and jug on the 1964 album Dave Van Ronk and the Ragtime Jug Stompers.

Ann included Bob Dylan in her anthology The Portable Beat Reader, solidifying Bob’s role in the pantheon of Beat writers. Bob was a friend; I met him a day or so after he came to New York in 1961. He, Dave, and I became friends and he spent a lot of time at our apartment, as did the three of us and his girlfriend Suze Rotolo when they met.

I became Bob’s manager a few months later and getting him work was incredibly difficult; I consistently heard from club owners: ‘Why should I hire this kid when I can hire Jack Elliott?’ Our business relationship lasted several months, although we all remained friends for several years – and Suze remained a close friend until she died in 2011.

Bob became friendly with and influenced by Allen Ginsberg, who he met in late 1963. The intellectual bond wasn’t surprising. When Bob started to write songs, he did so somewhat in the folk tradition, telling stories (‘Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues’) recorded for the first time on an audition tape he made for me to take to club owners in fall 1961. But, within a fairly short time, he was writing using metaphor (‘Masters of War’ and ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, both on an album released in 1963, and songs written subsequently). His shift to lyrics that comprised a flow of words followed quickly.

Not many of the singer-songwriters entered the ranks of the Beats. Eric Andersen, perhaps. I can’t think of others.

There were also people I met separately, or later, like Tuli Kupferberg and David Amram. I knew Tuli through Peter Stampfel when I started to manage the Holy Modal Rounders. He was an anarchist, and was part of the counterculture both alone and through his work in the rock group the Fugs.

Peter once talked with me about the possibility of my managing the Fugs, but I worked out of the apartment Dave and I lived in, and, while we hosted hordes of people every evening, we had agreed that we wouldn’t allow people who took hard drugs to come in, and we incorrectly thought the Fugs did so. Many, many years later, I learned that Tuli didn’t use drugs and didn’t let group members use them.

I met David Amram in the early part of the 21st century, in Rockland County, which I’d moved to in the 1980s. I was part of an environmental group that wanted to purchase the self-designed home and studio of artist and architect Henry Varnum Poor, who had lived on a narrow, winding road that was the haven of many artists between the early part of the century and the 1950s; we hoped to turn the property into an artists’ colony.

We had to include in a grant application a list of artists who would review applications, and one of the people I asked to be part of that board was David Amram, whom I had met once at an environmental party. Without even knowing me, although perhaps he knew the name of Martus Granirer, the man I then lived with, who had been a well-known photographer in the 1950s but who had become an environmental lawyer, David said ‘yes’. We didn’t get the grant and didn’t buy the property and didn’t start an artists’ colony.

Years later, I became friendly with David, who appeared at my book launch, which was sponsored by the creators of the Village Trip, a new phenomenon that produces events such as music by John Cage and speakers such as radio DJ and host Cousin Brucie in Greenwich Village each summer. Turns out he met Dave (Van Ronk) before Dave and I had met, although we’d never encountered him when we were together. And he knows other friends of mine, such as avant garde writer and filmmaker Richard Kostelanetz and musician Norman Savitt.

I’ve recently read his memoir Vibrations, published in 1968, and he’s lived an enviably exciting life, steeped in the music he writes and makes. He’s still a superb musician, composer, and storyteller, and has become a friend.

I want to differentiate between the Beats and the people who were called beatniks. The latter were kids who copied jargon that had been used by the Beats and by others who were around in the 40s and 50s, copied the way the media suggested the Beats dressed, and often took drugs as they thought the Beats did.

They and the tourists who drank beer flooded the streets of the Village on weekends, rudely driving onto the sidewalks and honking their car horns, loudly yelling to one another and to the ‘local denizens’, throwing cigarette butts and empty wrappers and other junk on the streets and sidewalks, and ruining the neighborhood streets for the people who lived and worked there.

The people who lived there hated them, and I and other folk music people despised them…but the coffeehouses and the folk singers made a living from them, so we had to ‘make nice’.

There was another element of the Beat movement. They always had been anti-establishment, rejecting what they saw as a materialistic society, championing nonconformity and free speech. In the 1960s and 70s, they became involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement. I was a socialist and also was opposed to that horror, but I had little relationship with them in that effort.

I was not only opposed to the war but, as a Trotskyist, I believed that the people of both North and South Vietnam had the right to choose their own government…and even US government officials admitted that, if they had been able to, the South Vietnamese would have chosen Ho Chi Minh, who the US was trying to keep out of that country, as their leader. I was part of a group that stated that in our own propaganda.

I did not then think, as the Beats did, that street theater or cultural events would affect whether or not the US continued the war. The small organization I belonged to participated in anti-war marches and demonstrations, but disapproved of flamboyant and illegal activities. So, I wasn’t part of many of the events the Beats were prominent in.

Ultimately, we’ve all made a difference. We’ve had an effect, we’ve helped change America.

©Terri Thal 3/2025

Terri, great piece. Thanks for posting it! As to "The War," my own personal experience, like many other young men my age, was that the Draft Board deemed me "1A," right out of High School. I turned 18 on September 9, 1969, and they wasted no time in sending me my Induction Notice just days later. "Report to the Oakland Induction Center at 8:00 AM, Monday," etc. I mumbled, "Fuck That!" I threw the letter into the fire place. As Arlo Guthrie so eloquently put it in his classic song, "Alice's Restaurant," "You mean to tell me that I can't go to Viet Nam to kill innocent women and children after being a litter bug?" Right On, Arlo! Some of my friends even moved to Canada, and one guy applied to be a "Conscientious Objector," and got it! (After long delays). He was my hero, kind of like Gary Cooper in the classic Anti-War film "Seargent York." But I was still nervous, watching the mail closely while waiting for the "Nazi Gendarmes" to show up at my front door with their handcuffs at the ready. Well, I never heard another peep from the Draft Board! I figured that with millions of guys to process, I kind of just "Fell Through The Cracks!" Now, for other Wars, I might have even enlisted, if I thought that it was for a good cause, (NOT, ha ha), but I didn't condone nor support that War, so today I have a clear conscious about it. So Peace and Luv, John Allen Cassady

Terri, I'm Neal and Carolyn Cassady's oldest and John's big sister. I love your essay. Interesting to hear how the Beats lived on the other side of the country. Isn't David Amram a jewel? There should be more people like him in the world....we wouldn't be in the mess we're in now.