The legend of Zimmerman

Bob Dylan delighted in the tales he could spin to embroider his early biography and Jack Kerouac adapted his own life for fictional purposes

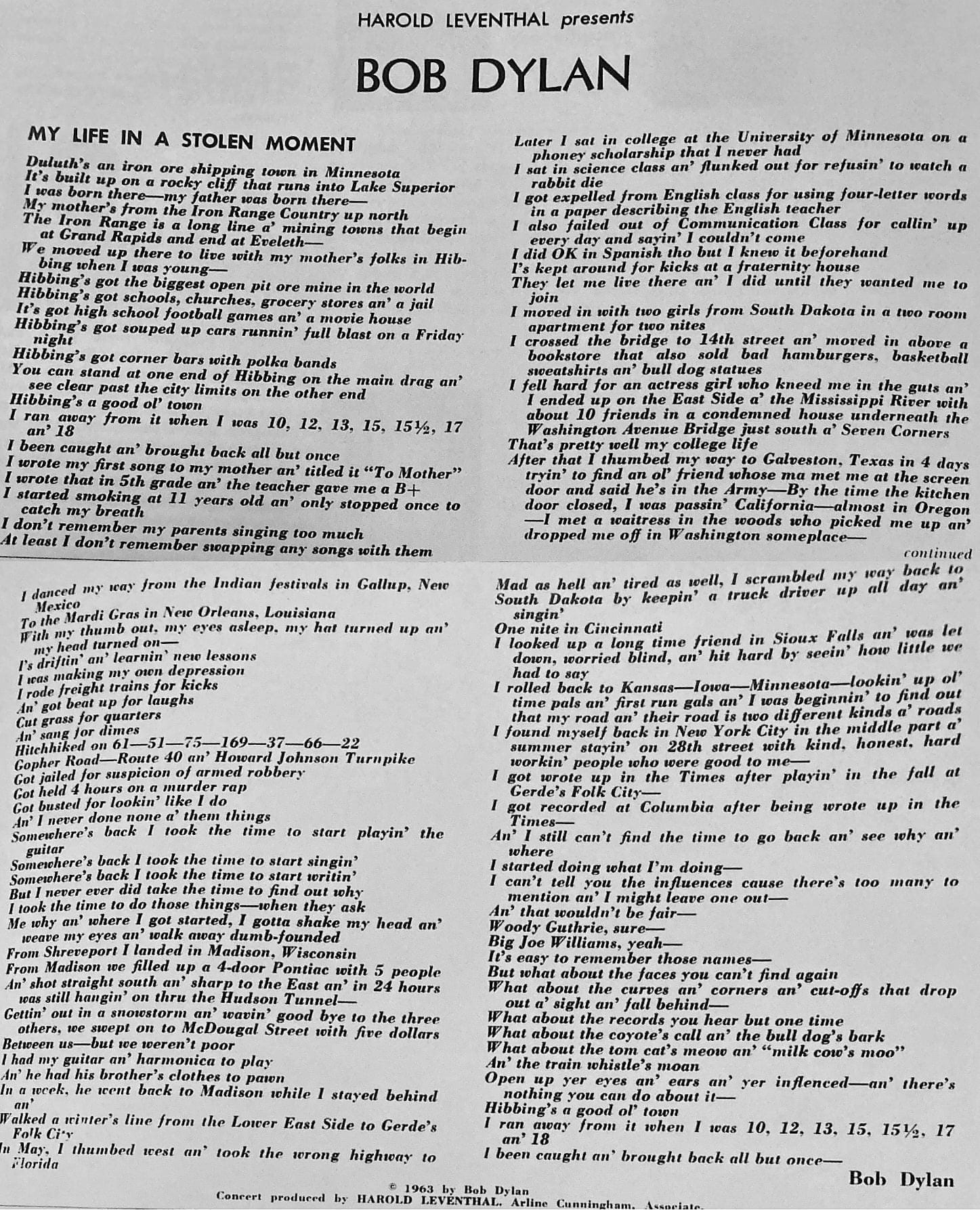

MY ATTENTION was drawn to a fascinating document produced as part of the programme for Bob Dylan’s 1963 concert at Carnegie Hall, New York City, a gathering of personal sketches and fragmented reminiscences compiled under the heading ‘My life in a stolen moment’.

Less a piece of free verse or a set of journal notes and more like a talkin’ blues, this body of writing is riddled with the delirious details of a misspent youth, hurtling across the massive geographical arc of the USA in multiple guises: hobo and hitcher, vagabond and thief, murder suspect and minstrel.

It is, of course, gripping stuff – the picaresque life of a Midwest teenager scraping his ripped-sole boots, from West to East, from North to South, on the roads and bridges, in the trains and backwoods, by rivers and through tunnels, enraptured by the very romance of the American cavalcade, a Hebrew Huck with a whistle and a stick.

With guitar always in hand, he even, almost incredibly, gets reviewed as a singer at Gerde’s Folk City and, quite unbelievably, gets a recording contract with one of the great labels then issues an album for the ears of the waiting world. A charming fantasy, surely?

We now know, of course, that almost all of this thrilling odyssey is just a fable. Virtually none of what Dylan describes actually happened to him and, as a young man and new arrival on the febrile Manhattan scene, he was more than happy to make his own legend up as he went along. The past was another country, somewhere up in wild wind Minnesota. And no one, probably not Robert Zimmerman himself, thought he was going to make it – make what? – so what did it matter.

One person on whom the newly-christened Dylan had pinned his youthful admiration was the novelist Jack Kerouac, a writer he had discovered through the poem cycle Mexico City Blues while studying, in a rather loose sense, at university in Minneapolis in 1959. By that time, Kerouac had established himself as the most exciting fresh voice on the publishing scene, drawing on his own frenetic and unsettled existence to develop a thrillingly original canon of his own: novels, essays, verse, travelogues.

Kerouac regarded his writings as a continuum, a dynamic thread, spanning all his experiences, from birth to, ultimately, death. His self-titled ‘Duluoz Legend’* would eventually aim to offer a complete literary autobiography – ‘like Proust only written on the run’ – framing home and family, friends and lovers, travels and adventures, religion and philosophy, even if he relied on made-up names for his associates at the demand of his litigation-fearing publishers.

To what extent the huge body of written text he produced was a legend – a dreamt-up and somewhat re-touched telling of an interesting life – and to what degree it was a completely truthful remembering, like an honest revelation in the confessional, we don’t know for absolute sure. Even a close follower of his output like me – I’ve read a considerable number of his novels not to mention numerous biographies – has not had time to carry out a forensic comparison of the fiction and the fact.

Kerouac’s good friend and poet Gary Snyder, the model for a central character in The Dharma Bums, the 1958 follow-up to the previous year’s On the Road, said some interesting and revealing things about the novelist’s process in a 2020 interview. Snyder, still alive at 91, remarked: ‘Jack was a novelist; he wasn’t a journalist. I am only one small model for the Japhy Ryder character. A lot of what Japhy Ryder does is fictional, but some of it is interestingly drawn on what Jack and I did together – the mountain-climbing scene is close.’

One thing that Dylan has not had to cope with is that fact v. fiction oppositional binary that can haunt the prose specialist. Poets are not asked if their work is factual or fictional and nor are songwriters, even if some critics and their fans will inevitably go looking for clues about their lives in their stanzas and verses.

It’s also worth saying, of course, that although Dylan admired Kerouac, befriended Allen Ginsberg and even wrote a 1971 novel called Tarantula that owed something to the cut-up constructions of William S Burroughs, the singer was not singularly obsessed with the Beat Generation crowd.

While he longed to be associated with them – the album Highway 61 Revisited plunders phrases from Kerouac’s 1965 release Desolation Angels and the photographs with members of that rowdy clan outside City Lights bookstore in San Francisco at the end of the same year are good examples – his reading went well beyond their books.

I finally consumed Richard F Thomas’ Why Dylan Matters, from 2017, during lockdown last year. It is a richly informed and erudite account of the songwriter’s interaction with the Greek and Roman poets, with the French Symbolists, with Melville and with the Bible, too, yet the Harvard University scholar makes no reference to Kerouac at all. So Dylan’s literacy is eclectic, not confined. The Nobel Prize winner has certainly done his homework.

As for fiction, Dylan has not been averse to weaving further webs of deception in other mediums. His widely-acclaimed Chronicles, Volume I was a beautifully written 2004 memoir but not necessarily an account bound by the requirements of the witness stand. The same applies to the 2019 Rolling Thunder Revue movie, steered by Martin Scorsese and cryptically subtitled ‘A Bob Dylan Story’, which deliberately played games with the truth for the amusement, it seemed, of the lead artist and its director.

So, these questions of fact and fiction, perhaps of faction, of veracity and deception, of biography and autobiography. There is no doubt that both Dylan and Kerouac had legend-building proclivities. Dylan was keen to fabricate another character, another personality, who was not straitjacketed by his boyhood days in an iron ore town on the edge of the Great Lakes. Kerouac, too, wanted to escape the limitations of Canuck, Catholic Massachusetts and set out to deliberately mythify his progress along the highway of possibility.

They were small town outsiders with ambition and big ideas and their remarkable discography and astonishing bibliography eventually lived up to their aspiration, I think we can all agree. Listeners and readers may want to know the real rocker, the real writer, but we are also entranced by the appeal of the fantasy, the power of heightened experience. Both of these incredible creatives were not averse to utilising such quixotic tricks in their creation of compelling art.

Note: Thank you to the music journalist Danny Cornyetz for mentioning the item from the Dylan programme

*Kerouac’s ‘Duluoz Legend’ is a self-effacing phrase debunking its grandiose style: ‘duluoz’ is French-Canadian slang for louse

Anything that Dylan the conjuring literalist of song who gets it from day one as an artist with the crappiest voice in history has got me from day one.

I benifitted as a 15 yr.old with other older siblings getting ‘it’ and we all heard on our folks magnificent stereo

which had been used only for musicals

being preformed locally and now blasted out Dylan .We thought this guy had it and to our nearing hip minds had also

‘got’ it.And , thou aged , almost still does!Unfortunately we have not all survived.So we salute that crazed hippy young lad who twisted up our appreciated young thoughts with his complicated young algorithms with his poetry magnificently!My thanks forever.