What tomorrow now knows: The Beatles, the avant-garde and Beat

A multi-album version of the Fab Four's Revolver prompts an exploration of their experimental influences in the heart of the '60s. Mojo encourages us to tune in, possibly turn on & maybe even drop out

IN 1966, the release of the album Revolver marked a sea change in the popular music landscape. The Beatles, already showing signs of accelerating sophistication on Rubber Soul, the LP which preceded it, cast off much of their lovable moptop whimsy, their image as global pop stars with a hoard of instant chart singles, and entered a more serious phase in their recording lives.

With Lennon and McCartney, not to mention Harrison, approaching the height of their composing powers and with George Martin in the producer’s chair, now fully at ease with his always sparky, sometimes spiky, Liverpudlian wards, the floods of creativity that had marked their early years became an ocean of sound.

The sequence of songs that emerged on the record revealed a growing intention to make albums that were not merely a gathering of hit 45s plus supporting material, but a collection that took the notion of the long player into a thrillingly groundbreaking phase: individual examples of technical invention that were never going to trouble the Top 40 panels but were part of a longer listening experience for a maturing audience.

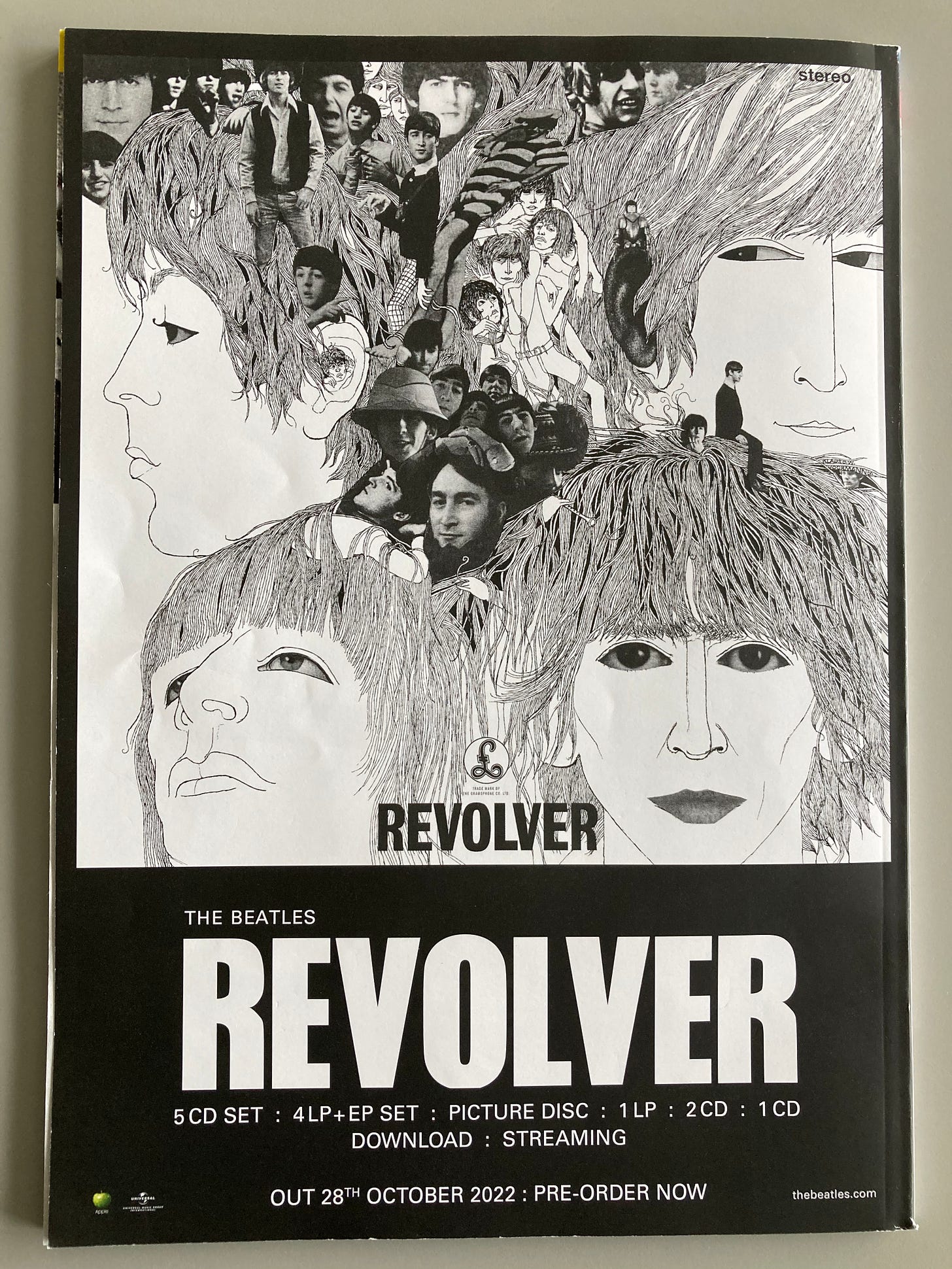

In keeping with a post-millennium trend, Revolver is now the subject of a massive re-visiting and re-packaging – in vinyl, CD and streaming editions – by the record label. Well over half a century after that album surprised and delighted its listenership, the LP is now widely considered to be the greatest album in the group’s catalogue, superseding even its successor Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, maybe even the finest such rock collection ever conceived full stop

Pictured above: Revolver re-visited in 2022

While some see the commercial recycling of this kind of classic work as simply a music business strategy to earn extra dollars from a historic source, others might argue that, in a disrupted digital marketplace, any means of generating further income or drawing attention to your prime artistic commodity when we all drown in a sea of musical material old and new, is to be excused.

But we could also claim that the particular richness and variety of the experiment underway in Abbey Road Studios around the pinnacle of the swinging '60s is well worth resurrecting by way of different versions, prototype recordings and other sonic blueprints that would eventually lead to the refined line-up of compositions on the original, official release.

As interesting, I think, is the plethora of influences that would feed in to the process of creation to inspire the songwriters, the musicians and the artistic director of this feast of audacious audio dishes – from ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ To ‘Eleanor Rigby’, ‘Taxman’ to ‘And Your Bird Can Sing, ‘I’m Sleeping’ to ‘Got to Get You into My Life’.

Mind-bending mysticism, mortality, marijuana and moans at the money grabbers largely displaced the standard love ballads that had dominated their highly successful discography up to that stage. But what or who was bringing a potent dose of the serious and the sombre, the oblique and the allusory, to the hyperactive minds of these still very young men?

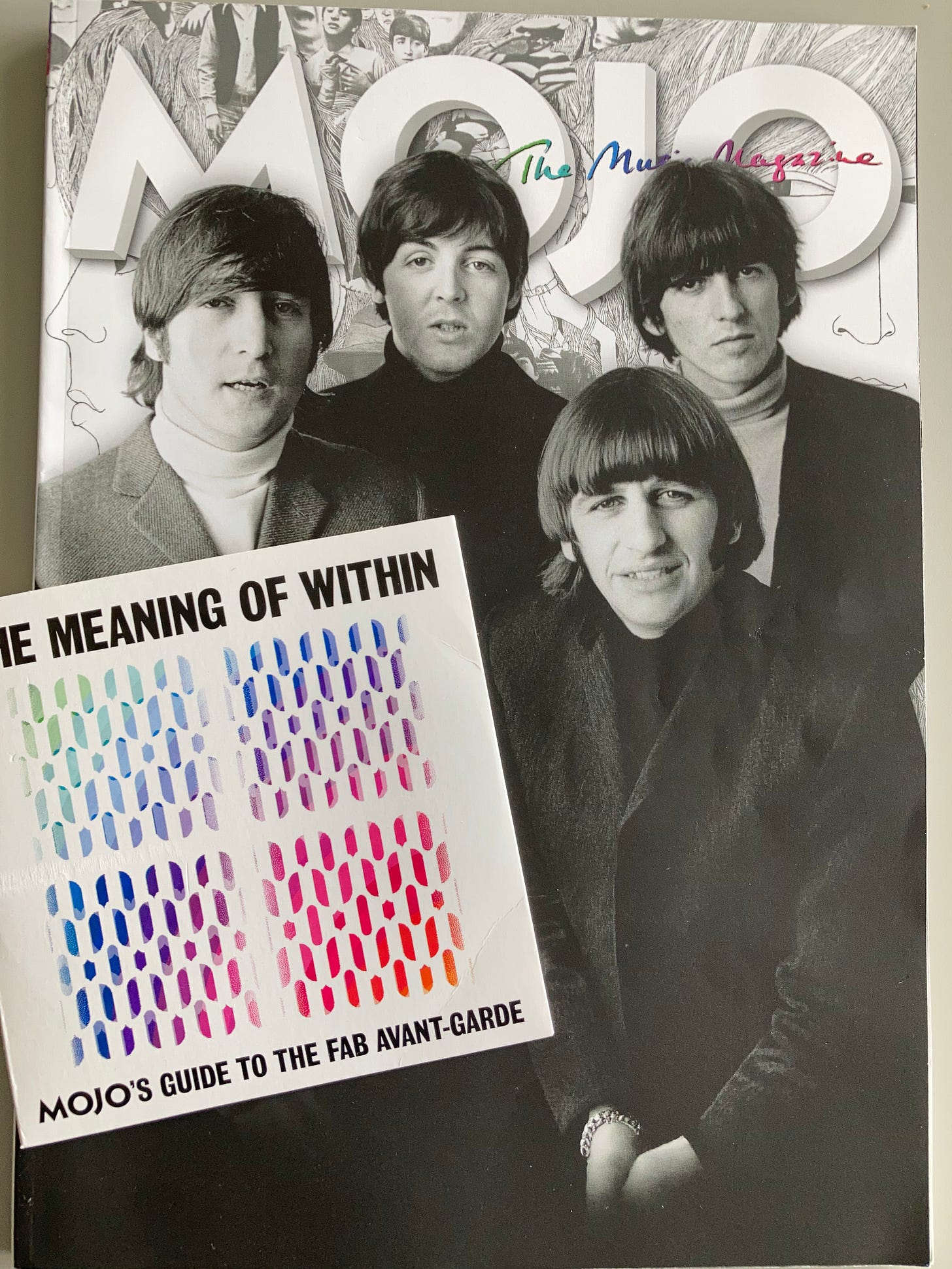

Trust Britain’s premier rock magazine Mojo to conduct a thorough post-mortem on this period of change and innovation for the Beatles themselves and broader Western society. In its latest issue, November 2022, the publication chases down some of the spirit of the Zeitgeist then haunting and shaping the pens and plectrums of the world’s leading band. And the import of the wider underground is clearly playing a role in moulding this significant moment.

Pictured above: The latest edition of Mojo plus the cover amount CD

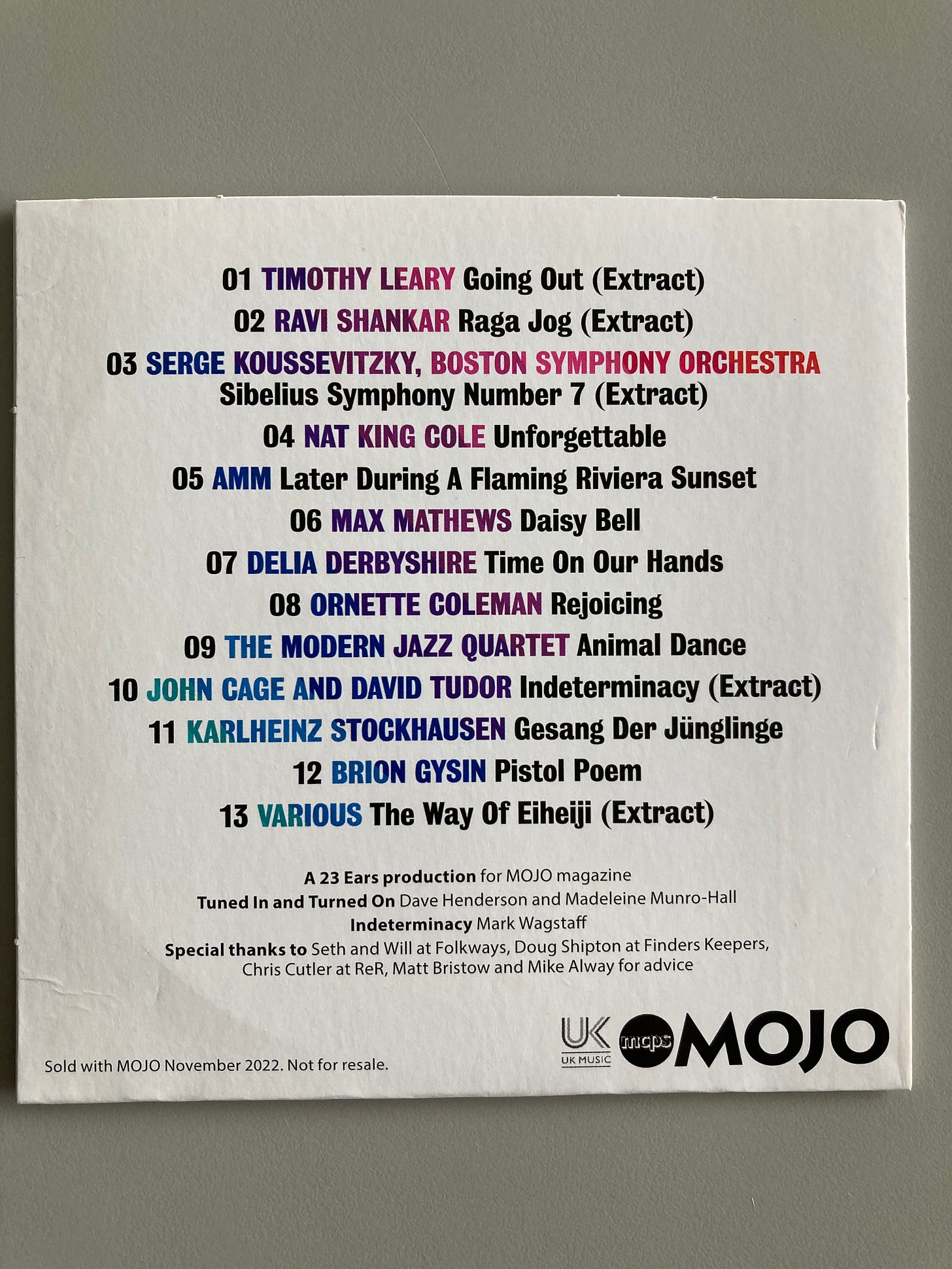

The cover mount CD which trails Victoria Segal’s fine and extended overview of the re-booted Revolver in its 21st-century form gathers a number of figures closely linked linked to the concurrent rise of subterranean forces and leftfield radicalism: Timothy Leary, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Delia Derbyshire, Cornelius Cardew, John Cage, Ornette Coleman and Brion Gysin to name only some.

Leary was the discredited Harvard psychology professor who had espoused LSD and preached its gospel. The German Stockhausen was taking notions of art music into unexplored technological realms. Derbyshire was one of the young geniuses operating in this now celebrated BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the UK.

Pictured above: Tracking down the influencers– the full cast of Mojo’s accompanying CD

Cardew was a British composer with a rare commitment to Maoism. Cage was the Black Mountain stalwart and extraordinary musical mastermind behind the stunning silence of ‘4’ 33”’. Ornette was the seismic saxophonist who had assaulted both bop and cool with his explosive retake on the jazz conversation. And Gysin had been the co-architect with his friend William Burroughs of the disorientating modes of the cut-up in art and literature.

The magazine explains, by way of an introduction to The Meaning of Within, this specially commissioned compilation: ‘It is spring 1966, and you been invited to a party at Paul McCartney and Jane Asher’s place in central London…There will be stimulating conversation, perhaps one. or two stimulating substances, and Paul may well share some of his latest literary discoveries from Barry Miles’ Indica Books.’

And there will be music, too, and the attached CD, subtitled Mojo’s Guide to the Fab Avant-Garde, attempts to distil some of that contemporary excitement and adventure via its track sequence of ‘psychedelic invocations, futuristic electronics, Indian ragas, Buddhist rituals, free jazz, avant-garde noise colleges and much more.’

Nor will Beat aficionados be surprised to discover that Burroughs earns a namecheck in Segal’s longer feature on the regenerated record set in a reference linked to the experimental studio McCartney set up in Ringo Starr’s flat in the capital’s Montague Square. The author of Naked Lunch utilised these state-of-the-art facilities for some of his own recording schemes around the same time.

The friendship between Burroughs and McCartney might seem a curious one – as Segal points out, the US writer actually hated rock ‘n’ roll. But Miles, that most sage of commentators on the transatlantic Beat community, puts those interpersonal connections into context.

‘Burroughs’ idea of good music,’ Miles points out, ‘would be Louis Armstrong, Viennese waltzes – because he studied medicine in Vienna before the war – and Moroccan trance music. He liked McCartney though, and they used to smoke a lot of dope together and talk about cut-ups and different ways of encouraging creativity by random interventions. Burroughs was fascinated to watch him working on “Eleanor Rigby”. Bill was amazed by how much. narrative he got into such a small space.’

So the Beatles, in the midst of their white hot revolution in pop art conceptualism, the group who had actually adopted the spelling of the name in tribute to the generation that Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs had launched some ten years before, were definitely still tapping into those literary tributaries to concoct fresh and revelatory experiences.

But they were also riding upfront on a supercharged vehicle, fuelled by a fertile life-force and ample psychotropic energy, with the thoughts and sounds of a countercultural network blaring in their minds and ears, about to pass their personal acid test with flying colours. With this bold CD collection, you can get a eclectic taste of what got the group’s mercurial mojo working at an electrifying moment in Anglo-American relations.

See also: Victoria Segal, ‘The shock of the new’, Mojo, November 2022

I've been looking forward to reading this one all day. What a fantastic account of the social fabric within which Revolver emerged, its consequence, and the role in our Digi-modern world this vaunted re-release properly plays. Bravo!

See also Beatles '66 by Steve Turner!