Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith by John Szwed (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2023)

By Steven Taylor

He always dressed in a coat and tie (as did men among the Beats before Jack Kerouac brought lumberjack chic to the Village), but Harry’s clothes were shabby, and the patches that covered holes in his coat were made of duct tape that had been inked and colored to match the pattern of the fabric. [1]

JOHN SZWED has written the first biography of the painter, filmmaker, collector, record producer, anthropologist, occultist and sometime indigent Harry Everett Smith. The book’s release comes just in time for a first solo exhibition of Smith’s work at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Szwed is well positioned to tackle the first biography of this most enigmatic of downtown denizens. Like Smith, he worked in multiple fields. In the 1960s, he supported himself by playing bass and trombone in jazz clubs. He went on to teach anthropology, African American studies, and film studies at Yale, and head Jazz Studies at Columbia.

Aside from his academic bona fides, he produced records (Rashid Ali, Joe McPhee, Myra Melford), and wrote for multiple periodicals (including the Village Voice, 1979-99), and in 2019 received a lifetime achievement award from the Jazz Journalists Association. He has published biographies of Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Sun Ra and Alan Lomax, and his Doctor Jazz: Jelly Roll Morton received a Grammy Award in 2005.

As a graduate student, Szwed first heard of Harry Smith when a professor told him that he should seek out and study with Smith. Although he was familiar with the downtown scene, he had never heard of Harry, and nothing came of it at the time. But in a way, this biography is a fulfillment of that directive, six decades after it was issued. He notes that he may have seen Smith at a Thelonious Monk show. He may have seen him, but he’s not sure.

The first time I saw Harry, I didn’t really see him either. Allen Ginsberg and I were walking along Twelfth Street in the 70s broken streetlamp darkness when a shadowy figure scurried across the street to avoid meeting us. ‘That’s Harry Smith,’ Allen said.

Pictured above: The new Szwed biography of Smith

I came to know Harry first as a recordist and producer, and later as a multidisciplinary artist and scholar, and an old man in difficult circumstances. Like Blanche DuBois (whose creator, Tennessee Williams, Harry advised on occult matters), Harry always depended on the kindness of strangers. I might have said he depended on friends, but he seemed a mystery even to those who knew him.

As Szwed notes, perhaps the biggest mystery about Smith is how he managed to live and work in San Francisco and New York for five decades without consistent income. Sometimes there was foundation support, or occasional gifts from art-world patrons, or money from wealthy would-be collaborators, but these things were sporadic. Izzy Young recalls Harry asking for two dollars to take a cab to Ginsberg’s to get five dollars for a cab uptown to ask Peggy Guggenheim for $2,000. [2]

How are we to understand the paradox of an artist whose life was almost completely outside the public’s view, who was always on the verge of calamity–if not death–and yet was so influential in so many ways? [3]

Harry Smith flew under the radar for most of his life, and was virtually unknown outside of certain circles of musicians, experimental filmmakers, occultists and anthropologists.

Painting is Smith’s least known area, because almost all of his pictures are lost; only a very few survive as photographic slides. As Szwed notes, art-world notoriety depended upon being ‘discovered’ by dealers and gallerists and championed in the art press. Harry never had that. And on more than one occasion, work was lost when he was evicted from various lodgings for failure to pay rent.

In 1964, while he was filming dances and recording Kiowa singers in Oklahoma, all that he had managed to preserve of his life’s work was thrown out by his landlord. Harry wandered the dumps on Staten Island for weeks, searching in vain for his works. ‘All of my paintings, all of my films, all of everything was destroyed.’ Some of the paintings had taken six or seven years to complete. [4]

Some of his recordings, drawings, fragments of linguistic notes and collected objects have been in museums and archives for decades, but without proper records so that in many cases, scholars and the public had no idea that Harry had done the work. I myself stumbled upon multiple audiotape boxes bearing only his name, without notes on content, on the day that I began graduate studies at Brown University. I had applied for a position in the ethnomusicology program the year Harry died, and largely due to his influence. Finding him in the music department archive floored me.

Throughout his life, he seemed obsessed with creating work, but he could be uncaring about what happened to it after it was made. Sometimes he deliberately destroyed things. He more than once threw reels of his films into the street. In the early 60s, he built a special projector to show his films with overlayed slides and gels, and then, while arguing with an audience member, threw it out of the window at the Anthology Film Archive.

In the late 1980s, Allen rescued Harry from a Bowery flophouse where he was wasting away. He’d caught the flu and had been unable to get out of bed to take meals. He moved into the small room off Allen’s kitchen where I had sometimes stayed, and we nursed him back to health.

In the summer of ‘88, while he was still regaining his strength, we took Harry with us to the Naropa Institute in Colorado, where he occupied a groundskeeper’s cottage, and with Allen’s support for rent and groceries and a stipend from the Grateful Dead’s Rex Foundation, he finally had a stable situation. He became known unofficially as the ‘shaman in residence’, showed his films, and lectured in the summer programs.

In February of 1991, he flew back to NY to accept an award and didn’t return to his Colorado cottage. Later that year, shortly before he died, he was seen by a friend at a pay phone outside the Chelsea Hotel with a stack of file cards – his address book – calling one acquaintance after another asking for help.

*

At the start of the book, Szwed is standing on broken glass in an abandoned factory near the Brooklyn waterfront examining 120 boxes of books and records – the portion of Smith’s library ‘that had survived his life on the streets, in other people’s homes, in rooms paid for by someone else.’ [5] Szwed notes that the old factory would soon be converted into the kind of studios and workshops that Harry never had.

Smith made his ground-breaking animated movies by hand, frame-by-frame, painting on 35mm film stock, bent over a table in various cheap rooms for a decade. ‘I hope you enjoy the films,’ he would say at showings, ‘they made me grey.’ In an interview I recorded in 1988, he said he had worked in that way because he didn’t have a camera. Harry dated his first hand-made film to 1939 and believed he was the first American to paint directly on film.

Not much had been written about him outside of academic film journals, and he published next to nothing himself beside LP liner notes. The biographer’s task was further complicated by the wash of outlandish legend that surrounded Smith, some elements of which might be true. Was he the son of Aleister Crowley, and was his mother princess Anastasia Romanov? Probably not. Was he the individual most responsible for the American folk music revival of the 1950s and 60s and its crossover into major-label pop? Arguably.

Harry made important work in multiple realms but, as Szwed details at length, he was first and last an anthropologist.

Smith’s paternal great-grandfather, a Union general in the Civil War and later lieutenant governor of Illinois, had ‘revived the rites of the Masonic Knights Templar in the United States.’ [6] Harry’s grandfather was a director of one of the largest canneries in the world. His maternal grandmother and mother taught in a Native American school in Alaska that had been founded by Russians (hence, perhaps, the myth of his mother being the lost daughter of the last Czar). His mother taught Alutiiq, Inuit and Han children in various schools before marrying Robert Smith in 1912. Harry was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1923.

He grew up in and around Bellingham, Washington, during the Great Depression. I had the sense from him that his father had been reduced to watchman in an abandoned cannery. Harry said that they were considered a ‘low family’ by the neighbors. As a boy, he suffered from some illness, perhaps rickets, that left him small in stature and with a spinal deformity.

He got into trouble once for reading his grandfather’s Masonic books, which he had found in an attic. Szwed says that, on his twelfth birthday, his father gave him a set of blacksmith’s tools that had been left at the cannery, and encouraged him to replicate various historical inventions, such as the first light bulb and telephone. Harry told me his father had told him to turn lead into gold. This was one of his vignettes, a collection of scenes from the past that he sometimes recounted.

Bellingham adjoins the territories of the Lummi, Samish and Swinomish peoples. At school, Harry heard a classmate describing a dance where they swung a buffalo skull on a rope and he wanted to see it. He knew that the last stop on the school bus was the Swinomish reservation, and one day he stayed on the bus to the end of the line. In a way, he never quite left that world.

By his mid-teens, he was making the first recordings of the ceremonies of the Lummi and learning to translate their songs. Between the ages of 15 and 21, he visited most of the Indian communities as far north as Vancouver Island. ‘In spite of later works in film, painting, and folk music and his study of the occult, he would always identify himself as an anthropologist.’ [7]

To me, this is the most striking thing about Szwed’s book. I had thought of Harry as a painter, filmmaker, sound artist, recordist and visionary producer of LPs, and had not realized the extent to which it was all tied together by anthropology. He never left the field.

*

Music was an early interest. He began his lifelong career as a recordist preserving his father’s cowboy songs and his mother’s ballads. He started collecting records just as the Great Depression and the rise of radio began to wipe out a diversity of recorded music that had catered to regional markets, and set up the media monopolies that by the late 40s had homogenized American music down to – as folk singer Dave Van Ronk said at Harry’s memorial – ‘Frank Sinatra and Doris Day’. These days, it may be difficult to imagine not knowing about folk music and the blues. That’s because the 60s made them mainstream, and Harry had a role in that.

During the war, Harry learned that among the items being collected for use in the weapons industry were 78rpm discs, which were to be melted down for their shellac. He knew he would be able to buy them for pennies. ‘Harry acquired some twenty thousand, and then began advertising for the rarest records, trading and selling what he had to get them.’ [8] He favored records made before 1932, because he believed the novelty of the technology meant that the performances were spontaneous and in the moment – the musicians were not aiming to preserve anything.

After studying anthropology for five semesters at the University of Washington, Harry dropped out, and during the last six months of the war, worked in a Boeing bomber factory. When the war work ended, he headed to the San Francisco Bay Area, intending to study at UC Berkeley with Paul Radin, who had done work on the Winnebago language. He sat in on classes, but never enrolled. Nevertheless, Radin hired Harry as his assistant.

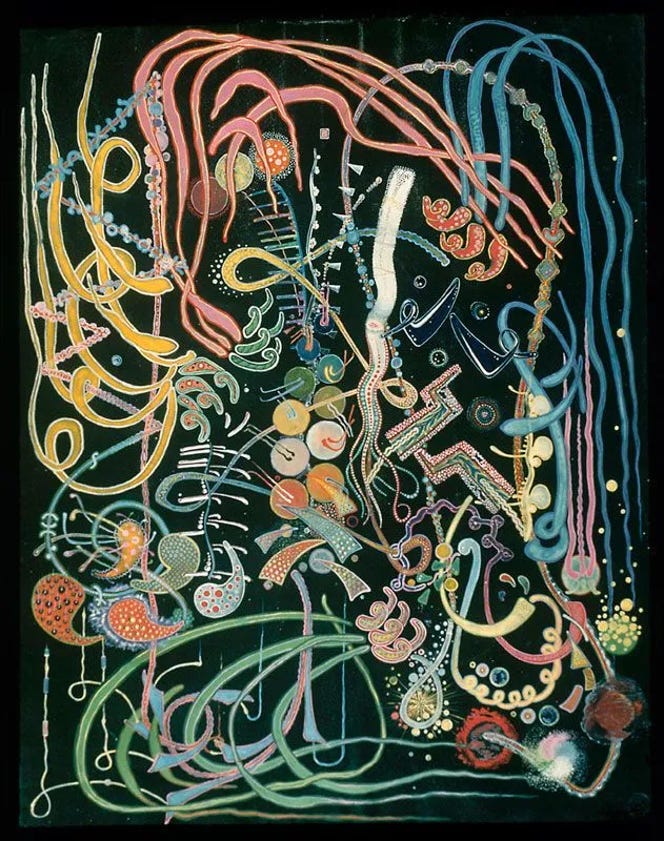

In 1948, he left Berkeley and took a room in the Fillmore district of San Francisco. An historically Japanese neighborhood, it had been made vacant when Japanese Americans were interned during the war and had become the home of Black workers brought in to do war work. There Harry heard live jazz more or less nightly and produced paintings that he considered to be transcriptions of various tunes.

Harry knew how to notate music; he’d done it at Native ceremonies. He probably also knew that musicologists distinguish two broad categories of transcription. The prescriptive variety tell you how to reproduce the tune; the descriptive kind are analogues for the music, but don’t enable you to reproduce it.

Pictured above: Manteca, 1948. A transcription of the tune composed by Dizzy Gillespie, Chano Pozo, and Gil Fuller in 1947.

One could argue that Harry invented the concert ‘light show’ in San Francisco, where he regularly projected abstract films and shifting colored patters to which players improvised (In correspondence, he noted that the musicians were eager to jam to the movies). He became occupied with jazz as an analogue to moving abstract images.

Smith and his friends, among them the surrealist poet Philip Lamantia, went to cinemas that showed only cartoons, which they considered the only Hollywood product worth watching. Harry was attracted by the seemingly endless possibilities offered by animation as opposed to the narrow range of Hollywood feature romance.

Animation could be infinitely more affordable and DIY than conventional cinematography since, as Harry demonstrated, it could be done with little more than reels of film stock and jars of ink. Visual artists had begun to embrace animation in the 1920s. Harry visited Oskar Fischinger, who had created special effects for Fritz Lang’s 1929 Woman in the Moon and did early work on Disney’s Fantasia. They saw animation as a new phase of fine-art painting.

When Ginsberg first met Harry, at the Five Spot in ‘58, he was watching Thelonious Monk and drawing diagrams – charting Monk’s rhythms so he could cut film to them. When he was able to borrow a camera or cobble one together from old broken castoffs, Smith made paper cut-out animations. His Heaven and Earth Magic (1962) features characters cut out of old mail order catalogues enacting a 19th-century psychedelic trip at the dentist’s. Szwed notes that Andy Warhol, Terry Gilliam, Robert Frank, Kenneth Anger and Jack Smith were fascinated by what Harry was doing with animation (the influence on Gilliam is most direct and obvious).

Upon first seeing the mutating geometric forms of Harry’s painted films (later collected as Early Abstractions), like many viewers, I immediately thought of Wassily Kandinsky. Harry had read Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual In Art, and Point and Line To Plane, where geometric abstraction, line, and color inform a cosmology.

Kandinsky had been influenced by his anthropological research among indigenous Eurasian people to whom he believed he was related. His abstractions were not purely non-objective. Many were adaptations of shamanistic renderings of St. George, whom the Komi people had conflated with their ‘sky riding man’ deity, who connects heaven and earth. [9] Like Kandinsky, Harry had begun his early training among indigenous people, and he was always looking to connect things such as Native American textiles, Ukrainian Easter eggs, Kabbalistic numerology, music (jazz, folk, the Beatles, and disco), and cardiorespiratory rhythms.

When discussing his films at the Naropa Institute in 1988-90, Harry said he favored music that expressed the ratio 72:13, because that is the ratio of heart beats to breaths per minute when one is relaxed and alert. He cut his films to express that ratio. (How the numbers related to things like image change v. frames per minute or musical metrics, he did not specify.) He called 72 and 13 ‘very important occult numbers.’ [10] A student of mine, Sue Salinger, who was a student of our distinguished colleague Rabbi Salman Schacter-Shalomi, told me that 72:13 is ‘a gematria for loving kindness’, which is expressed in Psalm 72:13: ‘He shall have pity on the weak and needy/And the souls of the needy shall he save.’

*

In the late 1940s, Harry had film showings at the San Francisco Museum of Art that began to generate a buzz. Then, in 1951, in the kind of self-sabotaging move that became a pattern, rather than build on his burgeoning west-coast reputation as a film artist, he moved to New York, arriving penniless at Penn Station, with no particular place to go. His collection of 78 discs, or some special portion of it, had been packed and shipped to the city.

The US underwent a cultural shift in the late twentieth century. Music played a role in that, and the change in the music of the period can be traced in part to a penniless artist looking to make rent by selling his collection of forgotten 78s to an independent record label.

In early 1952, Harry approached Moses Asch of Folkways Records, hoping to sell part of his collection for much-needed cash. Moe wasn’t buying, but suggested they put together a selection in the new format – LPs – which would allow them to put several songs on each side of a set of discs. Harry got a small advance and the promise of royalties on sales, and set about selecting and sequencing cuts for the LPs, and creating an illustrated booklet containing detailed notes about each track.

The resulting 84 tunes on 12 sides became one of the most influential releases of the vinyl era, not because it was popular with the masses, but because it underpinned a movement. Szwed says the Folkways Anthology of American Folk Music ‘was essential to the folk music revival’ and ‘to the shape of American music to come’, that it had ‘changed the trajectory of folk and rock’, and notes that it was ‘the Rosetta stone’ for the writers who would reinvent popular music criticism.

The 84 tunes on the Anthology were all recorded for commercial release between 1927 and 1932, when divisions of major labels like Columbia and Victor, as well as various small independents, produced music aimed at various markets. Polka bands were recorded for Chicago factory workers; Blues and ecstatic sermons by Black preachers were sold to the ‘race’ market; ‘hillbilly’ country fiddlers and old ballads were sold to the Appalachian descendants of Scots Irish immigrants; francophone accordion songs went to Louisiana Cajuns; and we got the first commercial products of what would become a billion-dollar business called ‘country’.

Harry drew upon all of these and more. The collection was essentially pirated copies of record label product, but Moe Asch had a political agenda. In the age of the Red Scare and the McCarthy hearings, he was saying, in effect, ‘You want American music? I’ll show you American music.’ In an effort to avoid prosecution for violation of copyrights, he marketed the records as educational material. In 1953, when RCA threatened litigation, he withdrew the records, and then went back to selling them again in 1956. Asch believed that people had a right to records that the labels failed to reissue, just as automobile owners had a right to replacement parts for their old cars.

Harry told a friend that his impetus for creating the Anthology came from noticing ‘that the folk or ethnic music of America was not included in the “popular” music of America. This is the sign of a very sick culture. . . . So, I felt I might be able to adjust that somehow.’ [11] In the early 60s, when Harry heard Bob Dylan on the radio covering some of the tunes, he felt that his intentions had been understood.

His sense of mission in making the Anthology may also have been influenced by Moe Asch’s oft-told tale of the turning point in his life that had resulted in the founding of Folkways Records. During the war, Moe had driven to Princeton with his father, the novelist Sholem Asch, to record Albert Einstein for a radio spot in support of Jewish refugees. After making the recording, Einstein asked Moe about his line of business.

Moe told the professor that he had the idea to record and make available the authentic music of the worlds’ people. Einstein said this was important and valuable work, and that he must pursue it. [12] In the version of the story that I heard from blues scholar and Folkways contributor Sam Charters, Einstein said, ‘It will take a Polish Jew to teach the American people their true history.’

The cover copy of the 1992 Smithsonian Folkways reissues of the recordings said, ‘The Anthology of American Folk Music is perhaps the most influential set of records in the history of recorded sound.’ In the liner notes, Greil Marcus called the Anthology ‘the founding document of the American folk revival’. There was an almost religious devotion to the thing. John Cohen, co-founder in 1959 of the New Lost City Ramblers, wrote that it introduced a generation of musicians to forgotten artists of the 1920s and 30s ‘who became like mystical gods to us’. Cohen called the anthology ‘a tremendous foundation for the counter-culture.’ [13]

Bob Dylan recorded ‘at least 15 of his own versions of the 84 records in Smith’s collections.’ [14] The 78s that Asch didn’t put out were deposited at the New York Public Library, where they were sought out by folk revivalists seeking ever more material.

In 1991, shortly before he died, Harry got a Grammy. The award presenter spoke as follows:

In 1952, a creative, eccentric painter, philosopher, anthropologist, and political activist produced three albums of folk music reissued from recordings made by major labels in the 1920s and 1930s. It’s called an Anthology of American Folk Music. It became the resource for a generation of young performers. For that work . . . to Harry Smith for Anthology of American Folk Music, 1952, and for his ongoing insight into the relationship between artistry and society, and his deep commitment to presenting folk music as a vehicle for social change, it is my pleasure to present our Chairman’s Merit Award to Mr. Harry Smith.

Harry was helped up the stairs to the podium. ‘I’m glad to say that my dreams came true. That I saw America changed through music. And all that stuff that the rest of you are talking about. Thank you.’

[1] John Szwed, Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, FSG 2023, p. 6.

[2] Szwed 225.

[3] Szwed 10.

[4] 220.

[5] Szwed 3.

[6] 20.

[7] Szwed 28-29.

[8] 57

[9] See ruth weiss, Kandinsky and the Old Russia, Yale, 1995.

[10] Szwed 91.

[11] Szwed 173.

[12] Peter G. Goldsmith, Making People’s Music: Moe Asch and Folkways Records, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998, pp. 3, 91.

[13] In Szwed, 148.

[14] Szwed 159.

Editor’s note: Steven Taylor, the author of this review, is a musician, writer and educator who was Allen Ginsberg’s guitar accompanist from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. He also taught at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, for a number of years. Today he is based in New York City. He has been a regular correspondent with and contributor to Rock and the Beat Generation.

See also: ‘Thr punk with the PhD’, March 27th, 2023; ‘Book review #15: False Prophet’, March 27th, 2023; ‘Beat Meetings #1: Steven Taylor & Gregory Corso’, February 24th, 2023; ‘Beat Soundtrack #7: Steven Taylor’, November 20th, 2021

Thank you for this fascinating "Book review" which reveals so much more to me about Harry Smith than I knew, from his curiosity and respect for Native american and other Indigenous cultures, to his jazz side, his spirituality, his poverty, his films, the spark that helped light the way for "And Now for Something Completely Different" and so much more.

Just devoured the biography and loved it SOO much!: <iframe src="https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fbruce.greeley.3%2Fposts%2Fpfbid02JEKL1VBQsvkCuGZ228UY1xgGg5KNyb3x3wBcrRe8AbrrZ7CepFxr4XGg5n34Bggol&show_text=true&width=500" width="500" height="684" style="border:none;overflow:hidden" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="true" allow="autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; picture-in-picture; web-share"></iframe>