Interview #4: Barry Alfonso

Was Rod McKuen’s minor classic ‘The Beat Generation’ a tribute or a parody? As his life story comes out in paperback, the poet’s biographer casts new light on the song and its author

Poet and songwriter Rod McKuen is much better known to American audiences than to British ones. I am aware of McKuen for two principal reasons: he was the author of the song that gave Terry Jacks a major 1974 hit in 'Seasons in the Sun', but, prior to that at the end of the 1950s, he had written and released a song called ‘The Beat Generation’, a piece that would, much further down the road, also inspire one of the great punk classics in Richard Hell and the Voidoids' 'Blank Generation' from 1976.

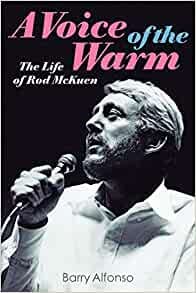

McKuen is the subject of an acclaimed biography, first published in 2019, by the Pittsburgh-based journalist Barry Alfonso. The paperback edition of A Voice of the Warm: The Life of Rod McKuen has recently been issued by Backbeat Books. The music writer, who has penned articles for Rolling Stone, has been assistant editor of Songwriter magazine and also contributed liner notes to many albums, including the Beat Generation CD box set, agreed to talk to Rock and the Beat Generation particularly about the Beat in McKuen’s remarkable life…

Please give a sense of what McKuen meant to readers and listeners in the US. Was he regarded as a serious poet? Was he better known as a singer-songwriter? His sales in both fields are immensely impressive. How would you share an impression of who this man was? Genuine and original artist, popular vocalist or middle-of-the-road entertainer?

After a long period of false starts and middling success, Rod McKuen broke through as both a singer-songwriter and published poet in the late 1960s. As you know, his massive popularity was very polarising – to millions of listeners and readers, he was a comforting voice, an inspirational figure, a kind of guru (Think of what Oprah meant to her fans 20 years later). To his detractors – who tended to consider themselves either guardians of traditional artistic standards or finicky hipsters who hated McKuen’s supposed blandness and sweetness – Rod was a cynical huckster who exploited the sentimentality of a gullible public. After delving deeply into his life and work, I found McKuen to be sincere in his desire to comfort and uplift his audience.

While he cared about his craft, he would sometimes latch onto trends and seek gimmicky ways to package and market his words, music and overall aesthetic. McKuen was a chameleon, a shapeshifter, a survivor of a brutal childhood and career setbacks who desperately wanted to prove himself. He was capable of outstanding work – ‘Love’s Been Good to Me’ and ‘Jean’ are deservedly enduring songs – but also willing to apply his talents to contrived and manipulative products that had little lasting value. There’s really no way to describe him simply other than he made many people happy at a time when they needed a friend.

Pictured: Barry Alfonso’s Rod McKuen biography, recently released in paperback

What was his relationship with the Beat writers of the 1950s? It seems he read with them in some of the same venues, but did he know those novelists and poets and what did they make of him and him of them?

McKuen was not a Beat, but he was a fellow traveller with the movement. He read poetry at the Jazz Cellar in San Francisco’s North Beach neighbourhood, a venue that also featured Jack Kerouac reading his work. There’s little evidence that he knew any of the principal Beats, though he did have a connection to them through Kansas poet Charles Plymell, who was friends with Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady. His ties with poets active in the San Francisco poetry renaissance – especially Jack Spicer – were real, though more social than artistic. He and Spicer knew each other through the Mattachine Society, a pioneering gay rights organisation. It was not uncommon for young bohemians in the ‘60s to have copies of Rod’s books next to those of Ginsberg and Gary Snyder. What McKuen shared with the Beats was an intimacy of expression, a willingness to tap into personal experiences and acknowledge loneliness, alienation and the desire for erotic adventure. Recall that Kerouac’s writing from On the Road onwards was inspired by the free-flowing prose of Cassady’s letters. There’s some of that unfiltered stream of consciousness quality to McKuen’s poetry as well. He found moments of magic in ordinary incidents, just like Kerouac did.

He made an album in 1959 called Beatsville. What was the aim of that set of recordings? Was it a tribute or was it a parody?

To my ears, Beatsville is half homage and half parody, based upon Rod’s own experiences among the poets, misfits and poseurs who frequented the Bay Area arts scene in the late ‘50s. The portraits he paints of them are exaggerated and sometimes played for laughs, but they mostly ring true. If he doesn’t take characters like ‘Frieda, who strips at the drop of a benny’ or ‘Raffia the poet, who is not only an angry young man but a dirty old man as well’ very seriously, he does seem to identify with their outsider status overall. There’s a reason why Beatsville keeps getting reissued – it’s funny, but also nuanced and sensitive. I have encountered painfully hip men and women like the ones Rod mocks and celebrates on this record!

The track from that LP, 'The Beat Generation', by Bob McFadden and Dor has enjoyed a long life but an uncertain reputation. Who were the artists on the record, how did they connect to Rod McKuen and was this recording a lampoon or a celebration? Clearly in mainstream American society, the Beats were regarded with certain scepticism, not to say fear…

Bob McFadden was a comedian and voice-over artist who collaborated with Rod on several novelty recordings. McKuen is credited as DOR (‘Rod’ spelled backwards) on ‘The Beat Generation’. The backup band is said to be Bill Haley & His Comets, who give the track some rock‘n’roll oomph. Rod runs through the usual cliches about beatniks – unkempt, unemployed, sex-crazed – with his tongue firmly in cheek. He plays the beatnik again on another collaboration with McFadden, ‘The Mummy’. It’s worth pointing out how beatniks were lumped in with monster movies, hot rods, surfing, teenage rock ‘n’ roll dances and other pop culture crazes of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Rod worked the beatnik, movie monster and teen dance angles on various records at this point in his career. By this time, of course, the serious intent of the Beat writers was being turned into the buffoonery of Maynard G. Krebs and the Rent-a-Beatnik fad. Rod was just hopping aboard the gravy train for fun and profit.

It could be argued that Rod McKuen in the 1960s was considerably more successful than most of his hip and heralded rivals – individuals like Ginsberg, Kerouac and Burroughs. What do you make of that fascinating tension between commercial success and artistic credibility during this period particularly?

That’s a complicated topic. I have the impression that Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs never took vows of lifelong poverty. I don’t think they were horrified at the idea of selling books and making money, though their ability to deal with financial success seemed to vary. What they did seem to want is a greater cultural influence – Ginsberg tried to advance the cause of personal liberation, while Burroughs wanted to ‘wise up the marks’ about the world’s control systems. Kerouac flirted with living a sort of bare-bones workingman’s life (as described in ‘October in the Railroad Earth’), but he also wanted to provide for his mother and enjoy some of the perks of fame. The Beats were accused to being con-artists and, by inference, interested in cash rather than serious art, a charge I don’t think is fair. Ginsberg and Burroughs seemed to have navigated the contradictions and pressures of a literary life fairly well; Kerouac, not so much. As for Rod McKuen, he never was ashamed of earning millions and didn’t see it as lessening his ability to speak from the heart to his audience.

McKuen was also responsible for raising interest in the Anglophone world in the output of the Belgian songwriter Jacques Brel. How did that happen and what effect did this have on that European performer's career?

Rod worked up a translation of Brel’s ‘Le Moribond’ (retitled ‘Seasons in the Sun’), which then found its way to Brel in France. Brel returned the compliment by translating Rod’s ballad ‘The Lovers of the Heart’ into French and recording it. This kicked off a long and productive relationship between the two songwriters. Rod didn’t restrict himself to literal translation when collaborating with Brel, sometimes venturing far beyond what the original lyric intended. The most enduring McKuen/Brel effort is probably ‘If You Go Away’ (adapted from ‘Ne Me Quite Pas’), which continues to earn royalties. It’s worth noting that the notorious mega-hit version of ‘Seasons in the Sun’ recorded by Terry Jacks tinkered with McKuen’s lyrics, which had likewise toned down the sardonic lines that Brel wrote for ‘Le Moribond’. It appears that Brel was not overly concerned with the English language versions of his songs – they earned him hits, but he didn’t comment on them. He and Rod do appear to have enjoyed a warm friendship beyond their professional association.

Did McKuen have any knowledge of the pastiche that Richard Hell created of his 'Beat Generation' song? What do you make of that extraordinary new wave response to McKuen's original?

As far as I know, Rod never acknowledged hearing or knowing about Richard Hell’s ‘Blank Generation’. I can tell you that he had a vast record collection and may well have had a copy of the record in it somewhere. Much of his collection ended up in the dumpster after his death – a shame. I don’t know if Mr. Hell has stated why he chose to rewrite ‘Beat Generation’ into a punk anthem – he probably was attracted to McKuen’s beatnik connections as well as Rod’s status as someone so un-cool as to be ultra-cool. I am reminded that Kurt Cobain was haunted by ‘Seasons in the Sun’ and made a live recording of it with Nirvana. ‘Blank Generation’ led to a degree of interest by punk fans in Rod’s catalog, particularly Beatsville.

Might you comment on critical reactions to McKuen…

Rod attracted widespread – but not unanimous – condemnation by the literary establishment. Karl Shapiro – a former US poet laureate and editor of Poetry magazine – was especially harsh. He dismissed McKuen as a mere ‘crooner’ who had no business calling his writings poetry – according to him, Rod’s work was ‘not even trash’. Interestingly, Shapiro though Rod’s poems were the latest example of a disturbing trend that began with the ‘bored, hysterical and narcissistic drivel’ served up by Allen Ginsberg and the Beats. Shapiro claimed that McKuen’s fans pressured Book World to drop him as a reviewer after he criticised Rod. He went on to condemn a composite cultural corruptor he dubbed ‘Dylan McGoon’ (an amalgam of Bob Dylan and McKuen) in later writings. For Shapiro and other critics, McKuen’s great crime was making poetry accessible to readers who did not meet their standards of sophistication. It should be mentioned that recognised poets like Charles Plymell and Aram Saroyan did find merit and meaning in McKuen’s poetry. As a singer-songwriter, McKuen didn’t get much attention in Rolling Stone or the rest of the rock press. Local newspapers in America and elsewhere often reviewed him favourably, however.

You’ve taken an interest yourself Barry in the Beats and you even wrote the notes for the well-liked Beat Generation CD collection, now an incredible 30 years old! What are your feelings today about those writers and their legacy?

Like most substantial and meaningful bodies of work, the novels and poems of the Beats have different things to offer to different generations. In my own case, how I've responded to the writings of Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs has changed over the years. Burroughs especially seems prophetic now – he foresaw more than even he could articulate. I recently re-read On the Road all the way through for the first time in many years, though I had read the scroll version about 10 years ago. I enjoyed it all over again, but my reaction to it wasn't the same as when I was 18.

I really liked writing the Beat Generation box set notes in 1991. Ginsberg told me they were the main thing he liked about it – he did not approve of the inclusion of stuff like the McFadden/DOR track, I suppose. But the Beats and the beatniks have been so blurred and mashed together over the past 60-plus years that it is all one big kidney stew, the kind you mumble imprecations over.

Pictured: The cover of the Beat Generation, a CD box set which included a recording of McKuen’s ‘The Beat Generation’ and notes by Alfonso